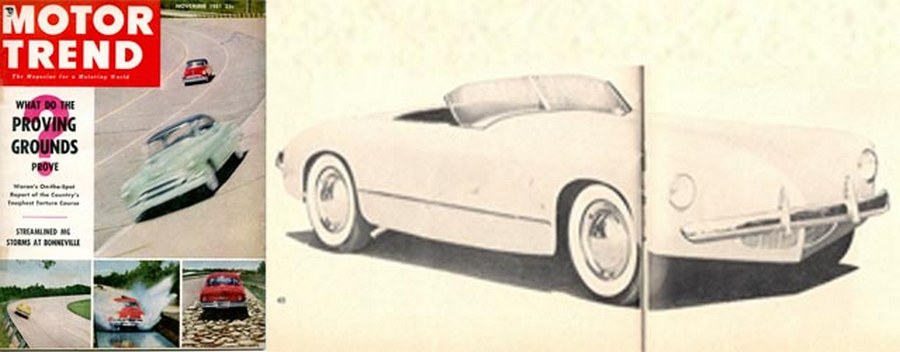

Fiberglass Sports Cars Debuted At The November 1951 Motorama Sponsored And Run By Peterson Publications. It Was Held At The Pan Pacific Auditorium.

Editor’s Note: Rollie Langston….this story’s for you! (maybe Guy Dirkin too and interestingly both are/were Byers SR-100 owners…)

—————

Hi Gang…

I’ve been holding back on you – but that’s now about to change.

I want you to believe in time travel – go back in time and truly try and understand American car design, postwar enthusiasm and confidence, and young American men’s dreams. That’s a hard one to achieve – isn’t it? But…nearly possible by going beyond the articles on fiberglass cars. Going beyond the new “wonder” material. We have to look at the synergy of the times and to do that we need the observations, thoughts, and ideas of a mover and shaker of the era – Walter A. Woron.

Walt was the first editor of Motor Trend which started in 1949. He steered the magazine and helped Bob Petersen (owner and publisher of Motor Trend Magazine and other Petersen publications such as “Hot Rod”) make it the success it is today. Without a strong foundation a company would have a tough time to build, learn, and grow and Walt was one of those guys who did everything right.

Click here to learn more about Walt Woron and his early years.

So why are we talking “Walt.”

As Dr. Alfred Lanning said in Issac Asimov’s epic novel “I Robot”……..“That, is the right question.”

The Big Bang! Motor Trend Magazine and the Petersen Motorama (November, 1951)

Walt Woron Was Editor Of Motor Trend From Their First Issue in 1949 Forward. He Wrote This Critical Editorial In The November, 1951 Issue Of Motor Trend.

In 1951, something special was happening. Throughout the 1940’s, fiberglass concept cars were being built:

First by Henry Ford in 1941. Then by Stout and Darrin in 1946. We recently discussed the IMP in 1949 and the Julius Rose “Comet” concept of 1947. And..Paul Omohundro proposed the first production fiberglass body in 1946 (Motor Trend Book 101, 1951) in a car he also called the “Comet,” and went on later to work with Frank Kurtis again and produce fiberglass production panels for the 1949/1950 Kurtis Sports Cars.

We were on the brink of something new. And then it happened. Glasspar, Lancer, Wasp and Skorpion. The fiberglass world would never be the same.

Each of these cars (Glasspar, Lancer, Wasp, and Skorpion) was officially introduced to the public at the second annual Petersen Motorama held at the Pan Pacific Auditorium on November 7th-11 in 1951. This was the first time the public could see a fiberglass car where they could purchase a body and build a car – or order a completed car directly thru any of these manufacturers.

The public ate it up and articles were published starting in this same month and year about how to build your own fiberglass car (click here for more information on the first public appearance of a production fiberglass sports car).

But it wasn’t just the public that noticed. And it wasn’t just a fad – as many professional automotive writers and analysts thought at the time. Something was happening and “fiberglass” was just part of a bigger picture. Fiberglass was just the “catalyst” for a much larger story, and Walt Woron saw this trend and nailed it on the head.

For the first time in automotive history, the “people” were having an impact – a profound impact – on the design of cars in America. And Walt Woron saw that, tasted it, liked what was happening, and wrote about it. Today’s story on Forgotten Fiberglass is the first of a two-part story focusing on two articles that appeared in this pivotal month of fiberglass history – November 1951. Both of these articles appeared in the same magazine, Motor Trend, and we’ll discuss the first article / editorial by Walt Woron today.

So…. Set your time machine dials to November 1951, get some coffee, put on some tunes from the times and let’s see what Walter A. Woron had to say about California car design and its soon to happen impact on Detroit.

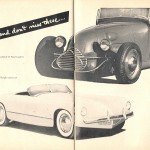

Although The Glasspar, Lancer, Wasp, and Skorpion All Appeared at the 1951 Petersen Motorama, Only The Lancer Appeared In The Show’s 1951 Program.

Your Editor Says….Amateurs Are Creating New, American Designs (Motor Trend, November 1951):

There’s something great taking place in the automotive world today, but too few people – to our way of thinking – realize it. It’s a transformation, being brought about by an active group of individuals whose very life is wrapped around its automobiles.

They look at their cars as more than just transportation, and are therefore constantly seeking ways to improve their design – whether mechanical or aesthetic. In this category are those persons who restyle, customize, experiment, and construct anything on four wheels. They’re expressing themselves in their own individual ways, and in the best manner they’re capable of. There’s a lot to learn from these imaginative designers and experiments – some good, some bad – but it all has a fresh, new approach.

How many of us look at a home-built sports car or a custom car and sneer, “What a bucket of bolts!” or “What a lead barge!” without realizing that it is the expression of a new thought or a different idea? New, sweeping curves, unique paint jobs, fantastic upholstery, all represent a break with tradition.

We’ve been copying carriage design for so long that it’s hard to change our way of thinking. This group, however, is pointing the way – to a truly American design. It has been freely admitted by top Detroit automotive designers that many innovations on production cars are the result of watching the developments of these enthusiasts who build their own custom cars, sports cars and hot rods.

Hollywood is even recognizing the impact that this group exerts, and is going to exert, on the automotive industry. In a new Clifton Webb film, the “car of tomorrow” driven by Webb is nothing more than a de-chromed Lincoln – a car that would be classed among custom car fans as a restyled job, and what they have been advocating for years.

If the automotive and movie industries are willing to admit that these enthusiasts are exerting a strong influence on future auto design through their amateur creations, there must be reason for us to pause and take a closer look. What are they striving for? What are they trying to accomplish when they change the mechanical aspect or outside appearance of a car? Change, for the change’s sake, or improvement of basic design?

Ordinarily, people are prone to accept things as they are – and to shy away from radical ideas. If the change is slight, we can adjust ourselves to it, although we may grumble in doing so. Even so, the majority of us do little to retard a change, or to further it. That’s why these automotive enthusiasts deserve a lot more credit than they’ve been given.

One way for us to give credit where it is due is to encourage these creative enthusiasts in the pursuit of their goal. This not only benefits them, individually and collectively, but in turn helps to provide us with a better end-product. And this, without a doubt, is what it will do.

So, the next time you see an unusual home-built car, don’t laugh at what you might think is a screwball idea or design. Take another look. Chances are you’ll be looking at the prototype of tomorrow’s car, or at least at “an experimental laboratory on wheels” from which may be borrowed styling, design, or engineering features for Detroit’s newest creation.

Walt Woron

Summary:

This is really a pivotal article for understanding why fiberglass provided such an opportunity to bring concepts and ideas to life for the enthusiastic American young men who were enterprising enough to design and build their own sports cars back in the 1950’s. It shouldn’t surprise you that many of these same folks later entered into the automotive design field and enjoyed success throughout their careers.

It’s interesting to note Walt’s reference to “Hollywood” and the use of these “new and unusual car designs” in movies that might impact Detroit. For…. it was less than two years later that the film “Johnny Dark” took this idea to the “nth” degree, and utilized many of these innovative fiberglass cars from 1951 – 1953 in their prototypical film of building and racing sports cars in postwar America. And I like to think….the fiberglass sports car world was never the same.

Hope you enjoyed the story, and until next time…

Glass on gang…

Geoff

——————————————————————-

Click on the Images Below to View Larger Pictures

——————————————————————-

- Walt Woron Was Editor Of Motor Trend From Their First Issue in 1949 Forward. He Wrote This Critical Editorial In The November, 1951 Issue Of Motor Trend.

- Fiberglass Sports Cars Debuted At The November 1951 Motorama Sponsored And Run By Peterson Publications. It Was Held At The Pan Pacific Auditorium.

- Although The Glasspar, Lancer, Wasp, and Skorpion All Appeared at the 1951 Petersen Motorama, Only The Lancer Appeared In The Show’s 1951 Program.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.