Caption: Henry Ford, at right, tells the author about his plastic-car plans. The cagelike object is a model of tubular framework proposed for cars.

—————————

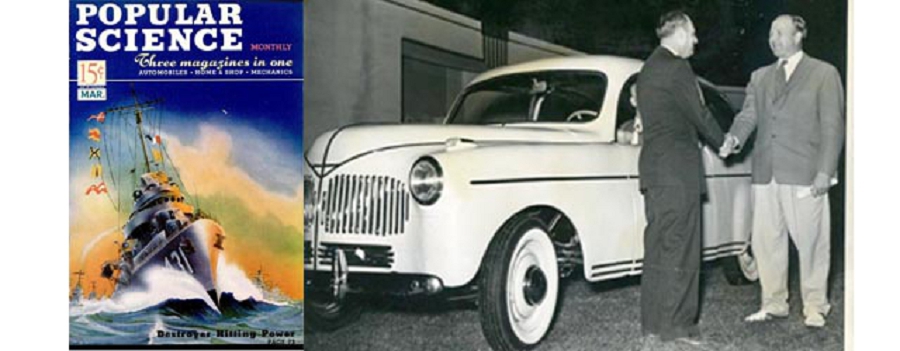

“No one is stirred more than (Henry) Ford at the prospect of seeing that all-plastic-bodied car….” Popular Science, March 1941

Read on to learn more….

—————————

Hi Gang…

In just 10 years America would see their first production fiberglass bodies. But that was ’51 and this article was in the Spring of ’41. And Popular Science Magazine was excitedly talking about the new plastic / fiberglass car that would soon debut.

It was the eve of America entering World War II….December ’41 and the attack on Pearl Harbor was less than a year away. And “plastic cars” were about to make their debut courtesy of the insight and innovation of Henry Ford.

Ford started by creating a replacement trunk lid in ’39 and the tests went well. Now in ’41 he was ready to built a car with a full fiberglass “plastic” body. Let’s peer into an article published by Popular Science in the Spring of ’41 and see what they had to say about the “soon-to-be-released” plastic car of the future.

Henry Ford Demonstrates Plastic Bodies for Cars

Mr. Ford Tells of Plans for Stronger Cars

Popular Science, March 1941

By Schuyler Van Duyne

Two years ago, Henry Ford sat at a table in a laboratory and instructed a young research chemist to go ahead and find out if plastic bodies for cars were practical. Recently I sat at that same table while Mr. Ford revealed that the chemist had brought in an affirmative answer.

I also learned that this research expert has just received additional instructions, this time to try out his idea on an experimental car. This test car will utilize all the secrets wrested from test tubes by 31 year-old Robert Boyer.

It probably will be full of what the automobile engineers call “bugs.” But when the bugs are removed, and when no more engineering and design problems remain, a new type of automobile will start rolling from the assembly lines of the gigantic River Rouge plant of the Ford Motor Company at Dearborn, Michigan. An automobile that will have plastic body, fenders, and hood!

Here the plastic trunk that had been hit with a sledgehammer by Ford is compared to a metal trunk hit also for comparison. The damage is substantial on the metal trunk.

“It will be a car of darn sight better design in every form” Mr. Ford said. “And don’t forget: The motor-car business is just one of the businesses that can find new uses for plastics made from what’s grown in the land. There’s no end to what can be done with them if we know how!”

It was not dissatisfaction with present cars; but with present raw materials used for making them, that led Ford to touch off the plastic-car research. He was looking for new uses for farm products. He’s found them, and the 77 year old industrialist has also found that they’ll give him and you and me what he is thoroughly convinced is a better automobile.

“Safer, lighter, and less expensive,” he says. He hopes other car manufacturers will soon be turning out plastic cars too, and if they do, he expects American industry to be off to new and more brilliant horizons.

Boyer, who shares his employer’s enthusiasm for the possibilities of the new use of plastics, points out that there are approximately 280 pounds of farm products in every Ford built today. There will be 200 pounds more when his plastic replaces sheet metal now used. Moreover, eliminating the sheet and metal and replacing it with plastics will result in a car 300 pounds lighter than it is today.

In the new venture, Ford said, he is “only interested in what comes from the land.” But he qualified this. “Industry, agriculture, and transportation are the three things that make the world go round,” is the way he put it, and the “industry” and “transportation” items no one can deny are already his province.

He now wants more than anything else to put the “agriculture” item in the position of being the pacemaker for the two others. In short, he wants America to grow her own raw materials to feed the factories that turn out the machinery of transportation–cars, trains, trucks, airplanes, vehicles of every type possible.

Few understand better than Boyer the intense enthusiasm Ford has for getting industrial raw materials from agriculture. A dozen years ago, Boyer, son of the then manager of Ford’s Wayside Inn near Boston, immortalized by Longfellow’s “Tales of a Wayside Inn,” was a serious-minded, athletically inclined high school student.

Ford and the boy’s father urged him to take a year at the Ford Trade School at Dearborn. He had been there two years when Ford happened one day upon an article in a technical journal describing experiments with chemicals derived from the soy bean. This little analyzed vegetable would thrive, he learned, in our climate.

Caption: Robert Boyer, directing plastic research for the Ford Motor Company, inspects a synthetic-resin trunk lid being tested on Mr. Ford’s car.

Convinced of Boyer’s capabilities, Ford set him up in what passed as a laboratory, but could be described more aptly as a well-kept barn, and told him to go to it: find out everything there is in a soy bean and what it could be used for.

A 1,000 gallon still was Boyer’s first piece of equipment. It still is the dominating object in the same crowded laboratory where Boyer’s 30 assistants–average age 24 years–work over benches laden with chemical apparatus. In the still, the soy bean was made to “tell all,” and among its many secrets was the fact that it possessed basic materials for a cheap thermosetting plastic.

Today, 21,375 tons of soy beans–grown in this country–go into plastics in each 1,000,000 Ford cars, the number turned out in an average year, and Ford operates one of the largest plastic-molding plants in the nation. And because of its many uses in other industries, the soy bean today ranks as our No. 4 cash grain crop.

But because soy bean plastics are relatively brittle, they will not provide the material for plastic bodies. Still, Boyer’s experience with them put him in a position to head up the plastic body research for his employer. Slightly more than a year after he got his orders, he had installed on Mr. Ford’s personal car a rear trunk lid which he had made of plastics.

To make it, he matted a mass of short and long fibers obtained from hemp, flax, and ramie. They are among the strongest fibers known. The matting was done in water. The water was extracted and a common phenol-resin compound similar to the raw materials of Bakelite was forced into them.

Set in specially made dies, the matted fibers and resin were then subjected to pressure and heat in a hydraulic press. The product, shaped to the desired size and curves, was tough, with a finish just as polished as the die in which it was pressed, and with chemical stability to withstand heat. In fact, while it can be charred at high temperature, no amount of heat would ever soften it again. In addition, it was virtually impervious to moisture.

The black trunk lid looks no different from the rest of the black sedan. In a recent demonstration of its toughness, Ford swung on the panel with an ax. The blow did not even leave a dent. But when he swung the ax on a conventional sheet metal trunk lid, the results were just what you’ve guessed–a deep dent and badly scarred paint.

Caption: Here a chemist studies soybean protein fibers, which were analyzed for possible use in cars.

The fiber materials in the tested lid, and in the plastic that will go into Fords of the future, are obtained from domestic crops. Currently, the resinous materials to be used as a binder are made synthetically. But if a way can be worked out to get them from the farm, it will be adopted.

Ford says that the test model Boyer is readying now will not necessarily set the style and lines of future Fords, and import style changes are being considered. Exactly what they will be is not yet being revealed. But there are several structural changes that he is glad to talk about.

There seems to be no doubt, for example, that the heavy bridge-girder-type chassis of present cars will give way to two strong horizontal steel tubes connected by tubular cross members. From each rear corner of the chassis, tubular arches of lighter weight will run diagonally toward the front of the car, crossing each other at the center of the roof, and ending near the engine mounts.

Additional lengths of tubing will connect and brace the arches and form the frames for doors and windows. All joints will be welded. To this tubular skeleton, the plastic body panels, fenders, and other surface parts will be fastened, probably be means of stud bolts set in as the panels are molded.

Similar studs would be used for mounting windows, door hinges and latches, and other parts. Engine, springs and other mechanical units would be mounted by conventional methods on the new-type tubular chassis.

The net result expected is a car frame 15 percent lighter and a body as much as 50 percent lighter. Ford sees in this important safety advantages in case of accident or collision. To begin with, plastic bodies will have ten times as much impact resistance as steel, a point he was proving when he swung the ax on the trunk lids.

Caption: Research with soybean compounds paved the way for the present experiments in plastic bodies.

That means the elimination of torn metal and dangerous jagged edges in collisions. In the second place, while tensile strength resistance to steady strain–of the plastic is less than that of steel, volume for volume, the panels will be thicker and will be backed up by the sturdy tubular steel frame which, Ford says, “will take care of that.” On top of it all, the car will have less dead weight to cause collision damage.

Significantly, Ford places greater safety below lower cost in the list of advantages in his plastic cars. He says also that they will be warmer in winter and cooler in summer because of less heat transfer than steel affords. They will be quieter, too, by reason of the material’s sound deadening qualities, and metallic ring will be eliminated.

Another problem Boyer solved was the added time required for the heat-and-pressure-molding process that his plastics must undergo, as compared with sheet-steel stamping. Just six times as much in fact. So to cut the time down to the requirements of the production line, Boyer will place six identical dies at once in each press, stacked up like dishes, and get six panels from a single operation.

As in most new industrial ventures, the list of manufacturing problems is long, and the time it may take to solve them cannot be estimated. That the bulk of them are solved for plastic cars becomes evident from the air of excitement and enthusiasm among researchers at the Ford plant.

Ford himself lets few days go by without looking in on the chemical-laboratory operations and consulting with Boyer and his associates. And no one is stirred more than Ford at the prospect of seeing that all-plastic-bodied car.

He will see it, in Boyer’s test car, early this spring. And the word going around Dearborn and nearby Detroit is that the first mass production plastic car will be on the market in from one to three years. Ford will not predict the actual date.

“I don’t know what I’ll be thinking tomorrow,” he says in reply to a question on the point. But his close associates do know what he’s thinking most about today.

Summary:

And so it came to pass that the first plastic / fiberglass car was born in the summer of 1941 – mere months away from the start of World War II – and the person who brought this innovation to the world was the same one who brought the innovation of mass production of the automobile to bear….. Henry Ford.

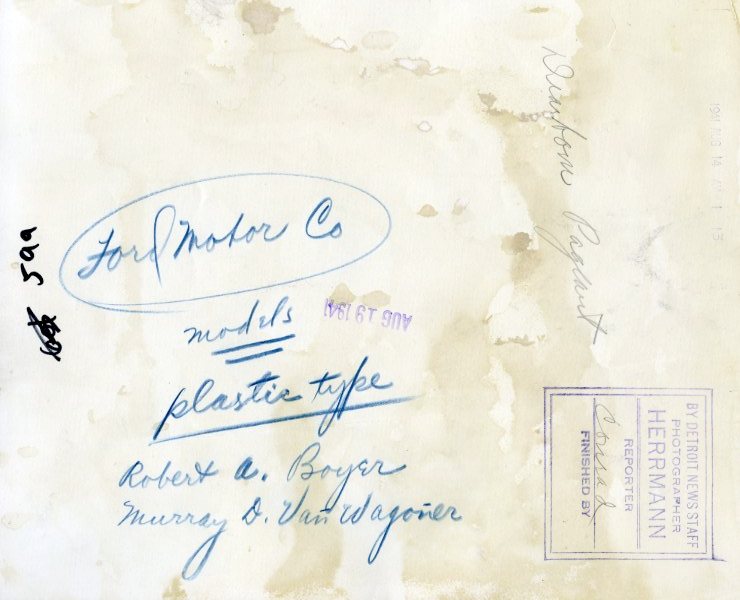

I recently came across a press photo from 1941 showing the famous Ford plastic car. On the back of the photo are identified the two folks in the photo: Robert A. Boyer (mentioned in the article above) on the left and Murray D. Van Wagoner (Governor of Michigan from January 1941 thru January 1943) on the right. Here is the photo and credit on the back:

Hope you enjoyed the story, and until next time…

Glass on gang…

Geoff

——————————————————————-

Click on the Images Below to View Larger Pictures

——————————————————————-

- Caption: Robert Boyer, directing plastic research for the Ford Motor Company, inspects a synthetic-resin trunk lid being tested on Mr. Ford’s car.

- Caption: Henry Ford, at right, tells the author about his plastic-car plans. The cagelike object is a model of tubular framework proposed for cars.

- Caption: Research with soybean compounds paved the way for the present experiments in plastic bodies.

- Caption: Here a chemist studies soybean protein fibers, which were analyzed for possible use in cars.

- Here the plastic trunk that had been hit with a sledgehammer by Ford is compared to a metal trunk hit also for comparison. The damage is substantial on the metal trunk.

What happened to this car?

I have another photo of the white car, found online, I think it was at Wayne State Univ, but now can’t be sure.

http://www.flickr.com/photos/hugo90/4383628868/