Hi Gang…

I’m honored to have another article to share with you about a rare fiberglass sports car from the UK called a Singer SMX. This article is written by Singer historian Phillip Avis who is part of the North American Singer Owners Club (NASOC) and publishes their stories in a club magazine.

Phillip has a keen interest in these cars, as you would imagine, and enthusiastically accepted our request to put together a historic review of this special fiber car from ‘cross the pond.

So off we go on another fiber-journey.

Take it away Phillip 🙂

The 1954 Singer SMX: Fiberglass Sportscar From the UK

By Phillip Avis: Editor and Publisher

North American Singer Owners Club (NASOC)

My interest in ‘fibreglass Singers’ harks back to 2002 when I ‘re-discovered’ the connection between a special fibreglass bodied Singer called the Vaughan-Singer Vibrin Roadster and a fibreglass company called Glasspar. This led to communication with Bill Hoover of the Glasspar G2 club and, through Bill, to Glasspar founder Bill Tritt.

We learned from Bill Tritt that one G2 body had been sold to Bill Vaughan, a well-known distributor of Singer cars at the time, and the car remained a one-off. Even so, there was a tantalizing connection between the ‘Vibrin’ and the Singer Company’s own effort to produce fibreglass bodied car which begged more research. But, in order to connect the two, a bit of back-story is required…

Centered, as it was, in Coventry and Birmingham, Singer Motors had suffered serious damage during the Second World War, compensation for which was very slow coming from the Government. In addition, although Singer had a number of war-time contracts, they did not prove lucrative enough to carry the company into the post-war era.

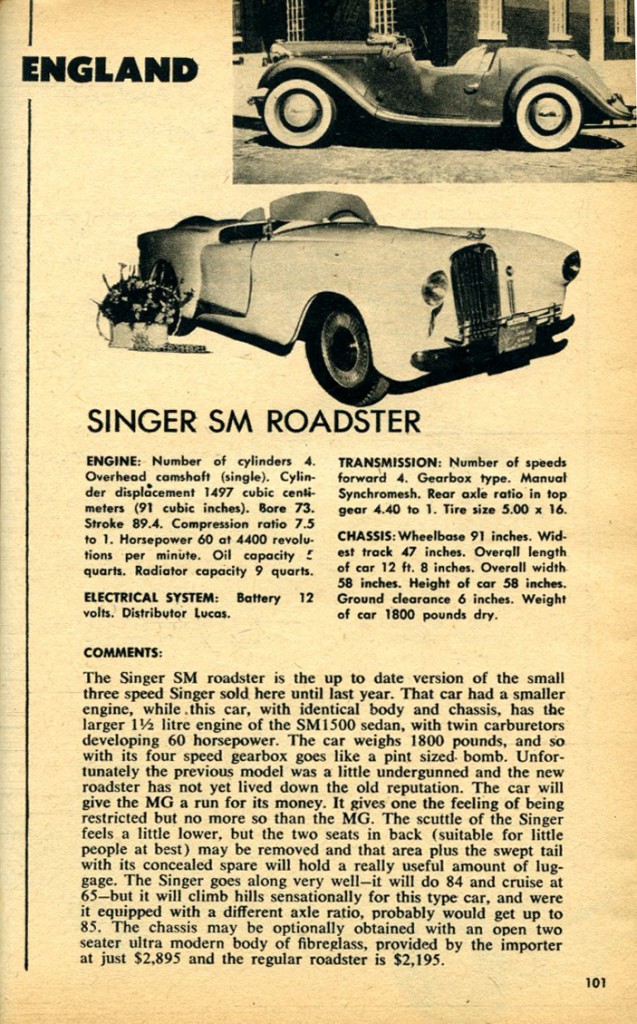

As the company entered peace-time, its model range consisted of basically pre-war designs; the Singer Ten and Super Ten Saloons, the Singer Twelve and the Singer Roadster. Hard earned funds were very quickly drained off in the design and tooling of their first new post-war design, the SM1500 saloon, which met with a luke-warm reception with its distinctly America style aimed at the critical export market. It was also priced at the very high end of the market for a 1.5 litre 4 cylinder car.

By 1953 things were looking grim. The SM1500 saloon, on which the company had pegged its fortunes, was still not selling as well as expected and 183 SM Roadsters from the previous year of production were still in stock. A change of plan was sorely needed!

The first step was to restyle the SM1500, which included fitting a more traditional grille and renaming it the Hunter. Part of this makeover included the bold decision to use glass-fibre for the front valance and bonnet, to be supplied by sub-contractor Marston-Excelsior ofWolverhampton.

Virtually at the same time, George Minton, head of the Special Projects Team was given the assignment to develop a totally new body for the Roadster, code-named ‘SMX,’ which, in a radical departure for the conservative company, would be produced completely in glass-fibre. The production Roadster could trace its roots back to 1939 and was distinctly pre-war in the same style as the MG TC and TD.

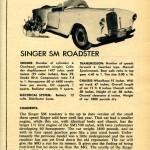

Minton and his team based the new model on the then-current version of the SM1500 4AD Roadster chassis. This meant a ladder frame, underslung at the rear, fitted with independent front suspension, a worm and sector steering box, a rear axle suspended on semi-elliptic springs and hydro-mechanical drum brakes. 15 inch wheels replaced the standard 16 inch and a larger gas tank was also fitted. The engine was the usual 1497cc single overhead cam unit based largely on the SM1500 saloon motor, but using twin Solex carbs.

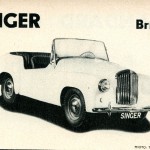

The design of the new Roadster was no doubt limited by the layout of the chassis, but its lines were clearly inspired by the new Hunter, which gave the cars a strong family identity. As with all Roadsters before it, the new model would be a 2 door open four-seater.

The new full-width body was built up in two large sections; the front bonnet assembly, which hinged forward, like the much later Triumph Spitfire and GT6; and the complete rear section aft of the doors. The other sub-components included the doors, bulkhead and dashboard. The main sections were supported by a 20 gauge tubular framework glassed directly into the 1/8 of an inch fibre-glass skin.

The floor was ribbed aluminum. There was no trunk lid. Access to the rear compartment was gained by folding the rear seat forward. The interior offered more room than the traditional Roadster and the dashboard was well stocked with bronze coloured gauges very similar in style to those used on the MG TD. Although the body was no lightweight, the SMX still proved to weigh less than the old car’s aluminum skinned ash frame with steel fenders and hood, so a performance advantage was also envisioned.

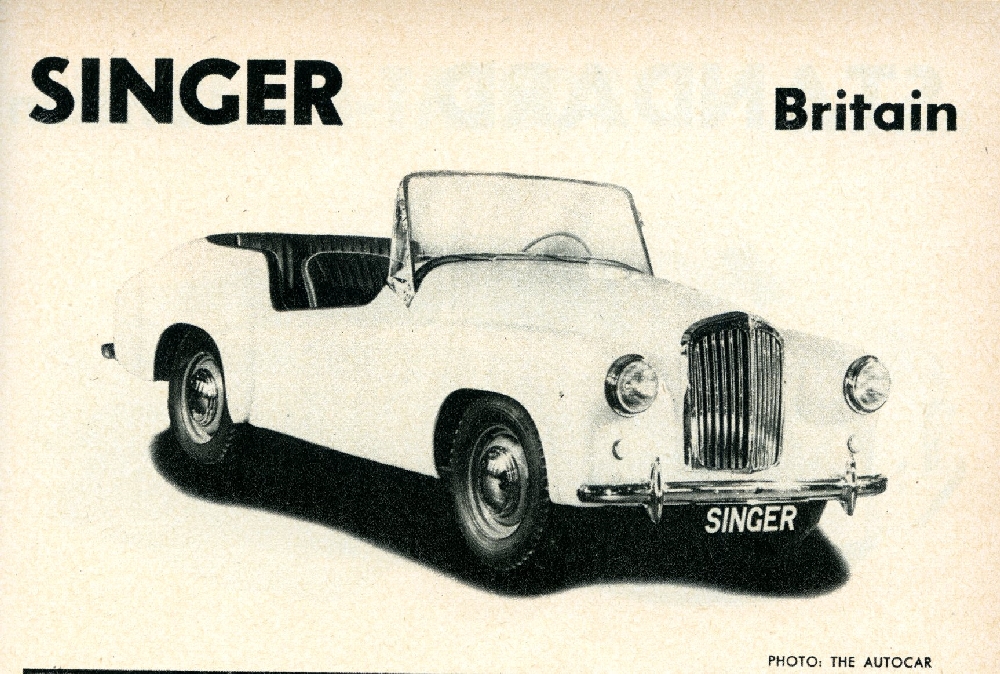

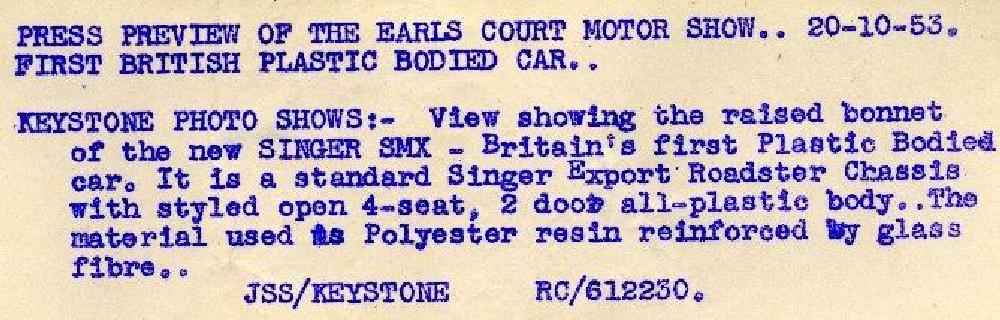

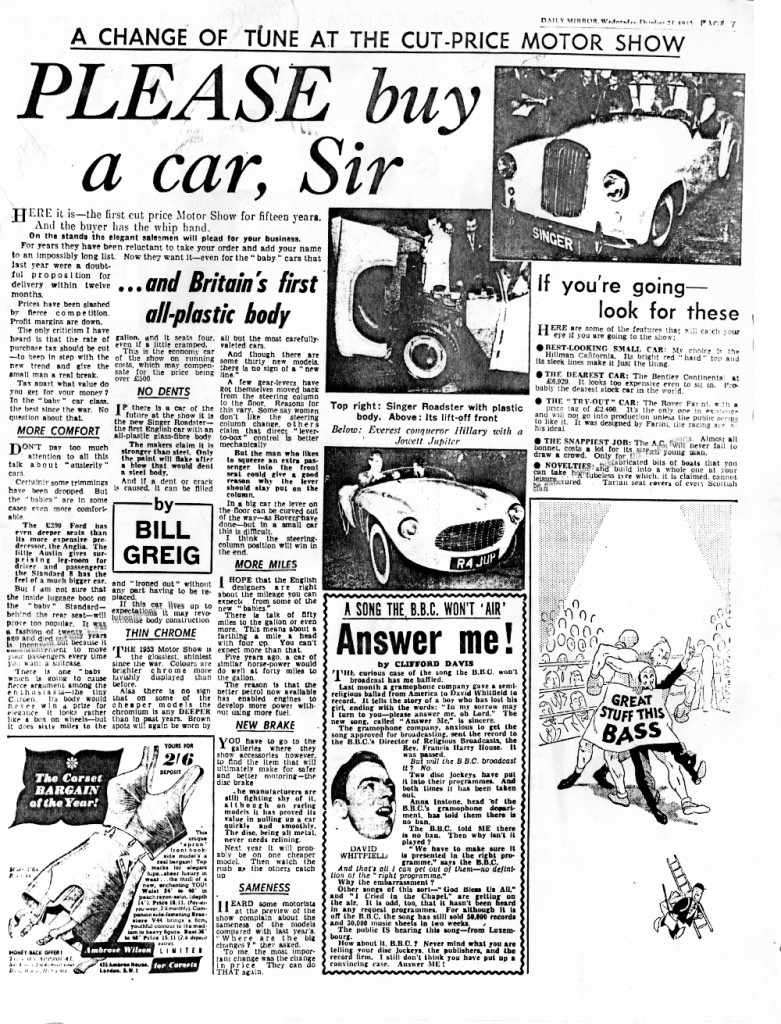

The first SMX prototype was officially unveiled to the press at the October 1953 Earl’s Court Motor Show, and, in keeping with the ‘Export or Die’ philosophy of the period, it was a left-hand drive. Painted in striking off-white with red interior it was critically acclaimed by the press. The Motor called it ‘lovely’ and Singer was hailed by The Autocar magazine as “Britain’s first manufacturer to announce a production model with a body shell made entirely of fibre-glass.” Pricing was never officially announced, but was rumoured to be around £670.00.

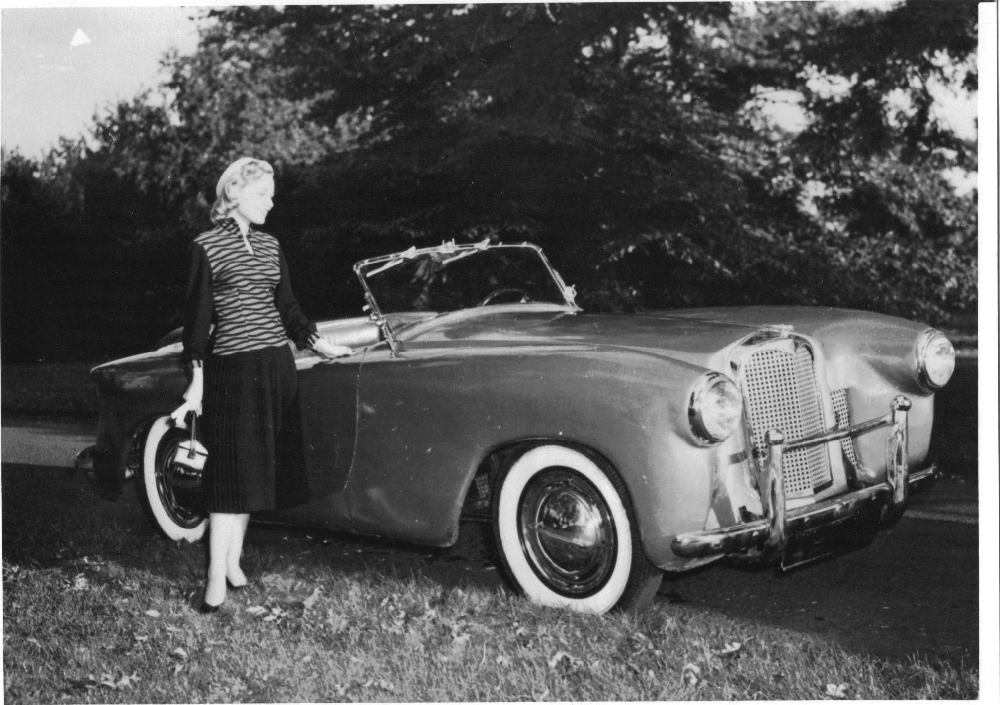

A contemporary photo of SMX 1 in one of the popular British motoring periodicals was captioned, “The call is heard from America for a fibreglass car” and it could well be that this was the influence of Bill Vaughan. He did much to raise the profile of the company in theUSAin the early 1950’s, both on the east and west coast. Besides the Vaughan-Singer Vibrin previously mentioned,Vaughanteamed up with sculpture Perry Fuller, who had built a body of his own design on the 4AD Roadster chassis.

Perry Fuller’s name is never mentioned in Singer records or literature as having been directly involved in the SMX development program, but a photo of a car very similar to Fuller’s, known as the ‘pre-SMX’, survives from the Minton family archive. It is feasible that via Bill Vaughan’s involvement, the Fuller body was pitched to Singer as a possible direction by which the company might improve trans-Atlantic sales of the very 1930’s styled Roadster. Indeed, Vaughanplanned to market the Fuller bodied cars via his dealership in the USA.

Design work began on the SMX program in January of 1953 and an article in JET magazine on Fuller stating his involvement with Singer as a body designer was printed in April 23rd, 1953, some time after the SMX program had begun. The Fuller car was still being raced in the USA in late May of 1953…at Bridgehampton on the 23rd… driven by Vaughan.

Although only 4 SMX complete prototypes are believed to have been built, perhaps as many as 15 bodies were made in various design studies as the program progressed. It is possible that the Fuller style car was considered as one of these design studies at Vaughan’s suggestion, considering how many of his ‘design signatures’ appear on the ‘pre-SMX’. Its crude nature, however, indicates a non-running model as opposed to a real completed car.

Sadly, no date or location is attributed to the only known photo, although it is a cropped version of a shot taken at what appears to be some sort of media gathering and includes a standard Roadster in the photo call. If there was any real involvement ofVaughanin the SMX project, it was a moot point as he had a falling out with Singer and had severed all ties by the summer of 1954.

As SMX 1 was enjoying praise from the Press of the day, another 2 prototypes were being laid down, each of which differed in details as the team sought to refine the design. While the company was still dithering over whether to bring the SMX to market, the Hunter, however, did go on sale in the fall of that year.

In October 1954, Marston Excelsior made a bid to Singer to produce the SMX bodies, with tooling up costs at around £7,500.00 and a production run at £160.00 per shell, but the delivery and quality of the Hunter panels had been variable, forcing Singer to tool up for steel replacements, so the offer was not taken up. By the time the 4th SMX had been assembled, the project was wound up, even though it was mentioned at the 1954 Motor show as being ‘available for export only’.

Another interesting project that Singer had undertaken at this time was the development of a double overhead cam version of the SM1500 engine designed in conjunction with HRG. A number of ‘pre-production’ engines were built and the first model to benefit was supposed to be the Hunter, which, in twin cam form, was to be known as the ‘75’. It is fair to assume that the SMX would not doubt have received the same motor had the project gone ahead. At least 1 engine is known to have survived in an HRG.

The SMX was certainly a novel, some might say almost desperate, attempt by this grand oldCoventryconcern to go in a bold new direction. Initially perhaps fibre-glass body design and construction appealed to the Singer management, who saw it as a way to ‘fast-track’ into the fibre-glass craze sweepingAmericaas well as a cheap way to produce a new, fresh, transatlantic design on the well-proven Roadster platform.

In the end, Minton and his team must have realised that the slow and labour intensive production methods required to produce a fiberglass body at the time did not make economic sense for large volumes. In addition, the failure of Marston Excelsior to deliver a consistent quality product in a timely fashion was a strong indicator the technology was still in its infancy and cast doubt on the SMX as viable.

By the summer of 1955, with debts mounting to unsustainable levels, Singer bravely laid down a new model program which included a Roadster using the HRG / Singer DOHC engine. Sadly, it was not to be. As the New Year bells rang in 1956, one of Britain’s oldest car manufacturers was swallowed up by the Rootes Group, an irony in that Billy Rootes had served his apprenticeship at ‘The Singer’ at the start of his career.

Of the all the prototypes built, only SMX 2 is known to have survived. It is a right-hand-drive version and very similar to SMX 1. It is currently owned and shown by Bill Haverly in theUK, who is also the Roadster Registrar for the Association of Singer Car Owners.

Phillip Avis

Summary:

Great job Phillip, and thanks for such a detailed review of this marque and car. For those of you interested in learning more about Singers, the best place to start is the website of Phillip’s club. Click here to visit the North American Singer Owner’s Club and review their cars in more detail.

Less than 200 Singers – both pre and post war – have been found in North America. And none are Perry Fuller’s car or the SMX model Phillip discussed above. Singer sports cars were the basis of many sports car specials from back in the early and mid ‘50s. Will you be the next person to find one of these Singer special sports cars from a bygone era – maybe even the missing Fuller car or an SMX???

Start looking gang! We’d love to hear what you find.

Thanks again to Phillip for his hard work on this article.

Hope you enjoyed the story, and until next time…

Glass on gang…

Geoff

Update: February 23rd, 2012: But Wait….There’s More!

Great news! There’s more thoughts on the heritage of the Singer SMX to share 🙂

Remember that it’s going on nearly 60 years since the debut of this car, so we can only speculate some of what must have happened “back in the day.” Peter McKercher sent in the following contribution offering his thoughts on what might have been some of the “behind the scenes drama” in the transition from the Perry Fuller Singer Special (click here to review) and the SMX history and heritage as expertly reviewed by Phillip Avis. Here are Peter’s thoughts – and a picture below as well.

Take it away Peter:

One of the big stories behind the story, of course, is the relationship between Fuller and Vaughan and Fuller and Singer. The Vaughan-Fuller relationship, particularly as it pertained to Fuller’s creation, was well established as early as the fall of ’52 and this ad from the February ’53 issue of the International Car Review shows a marketing drive well under way to promote their joint effort. The car would appear a couple of months later in April at the 1953 International Motor Sports Show at New York’s Grand Central Palace, where Vaughan and Singer Motors both had booths.

The Jet article reference to Fuller’s relationship with Singer and how he might assist in the SMX design program appeared directly after the show, which would lead one to wonder what discussions went on between them and perhaps to the exclusion of Vaughan. There has always been this unanswered question about why Vaughan split with Singer Motors in 1954. Did Singer do a deal with Fuller that excluded Vaughan’s participation? Did Fuller jump ship to take advantage of what he thought might be a better deal with a bigger company? Did he leave Vaughan’s long standing dream to produce his own fiberglass sports car in tatters. Did Singer kill a fledgling project that might have led to a production fiberglass sports car in America to develop its own SMX?

——————————————————————-

Click on the Images Below to View Larger Pictures

——————————————————————-

I have 54 Singer Roadster in unrestored condition In Southern Oregon. It has 1600 Pinto engine and 4 speed installed before I got it. I have never driven it and I put it away 15 or so years ago and will probably not get out to work on it for a few more years.

I am interested in these cars (as I am in all old cars) and would like to keep up on the club activities. Thanks, Val

Yes and Vaughan brought at least one to New York and was actively marketing both a coupe and open version of it at around the $3,000 mark. Presumably he sold the Coupe that he displayed at the 1953 New York International Motor Sports Show. Interestingly, the ugly little car that Fuller designed was to be priced at only about $100 less.

Ghia-Aigle proved that it was possible to clothe the little Singer chassis with attractive bodies in both roadster and coupe that were not all out of proportion.

What a lost opportunity the Singer SMX was. Who gave the ok to build such a crook looking car. If the then British stylist were so hopeless why didn’t someone call on the Italians for help as would happen in the coming years.