Hi Gang…

I love stories about fiberglass cars built “back when” that were carefully crafted and have an interesting history in terms of ownership and build. And this one fits the bill in every way.

It was built by Dick MacCoon – a friend of Doc Boyce-Smith as reported in the article – and part of the family that owned “Grant Piston Ring Company” in Los Angeles, California. And what a car it was. Here’s how they opened the article:

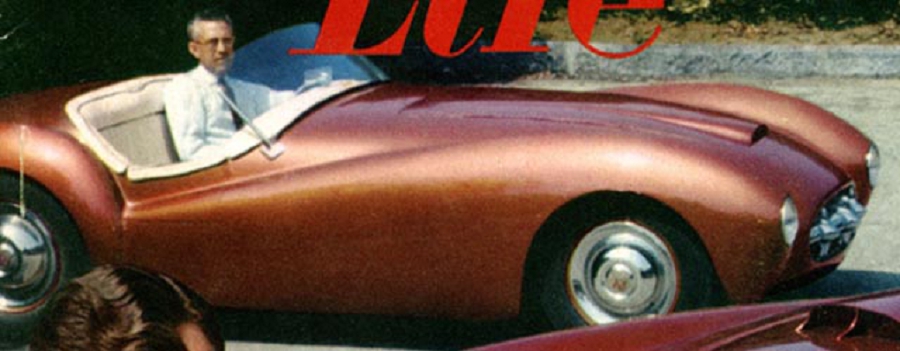

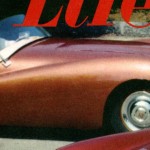

“You talk about custom cars – you haven’t lived until you’ve met this bronze fiberglass job!”

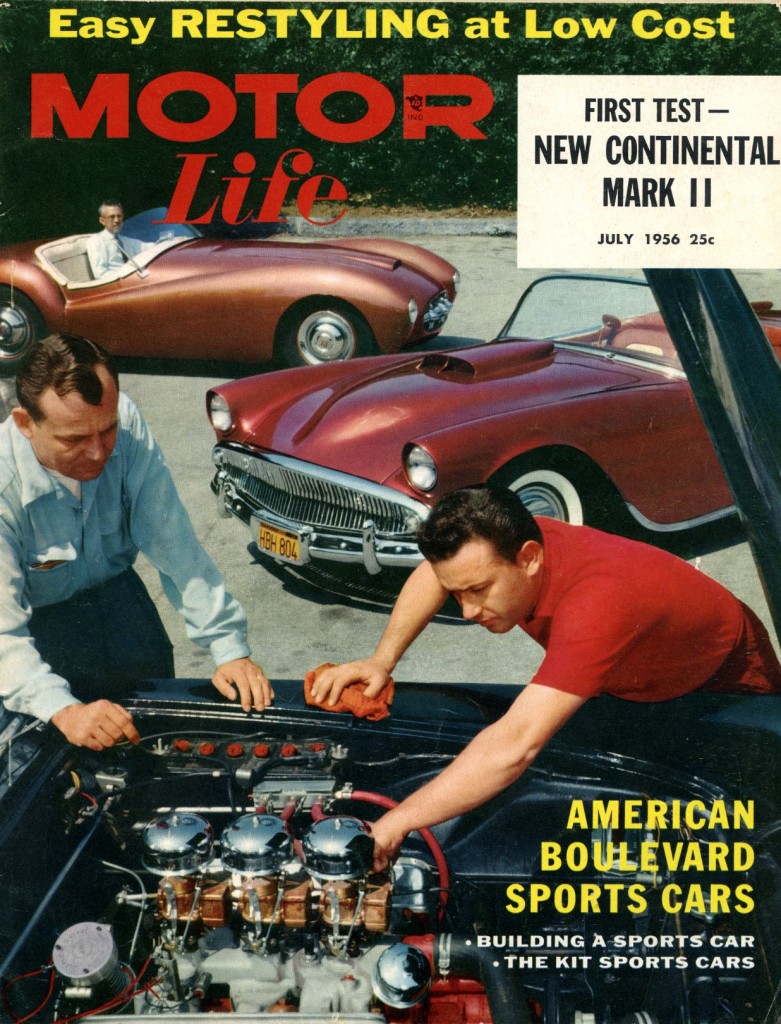

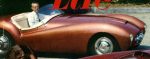

Not a bad opening line for any sports car of the era featured in a magazine. But this wasn’t the only feature for MacCoon and his Victress. His car would later appear on the cover and inside of Motor Life Magazine in July of the same year, as shown below:

Here are some other highlights you’ll read about concerning the “Bronze Bomb:”

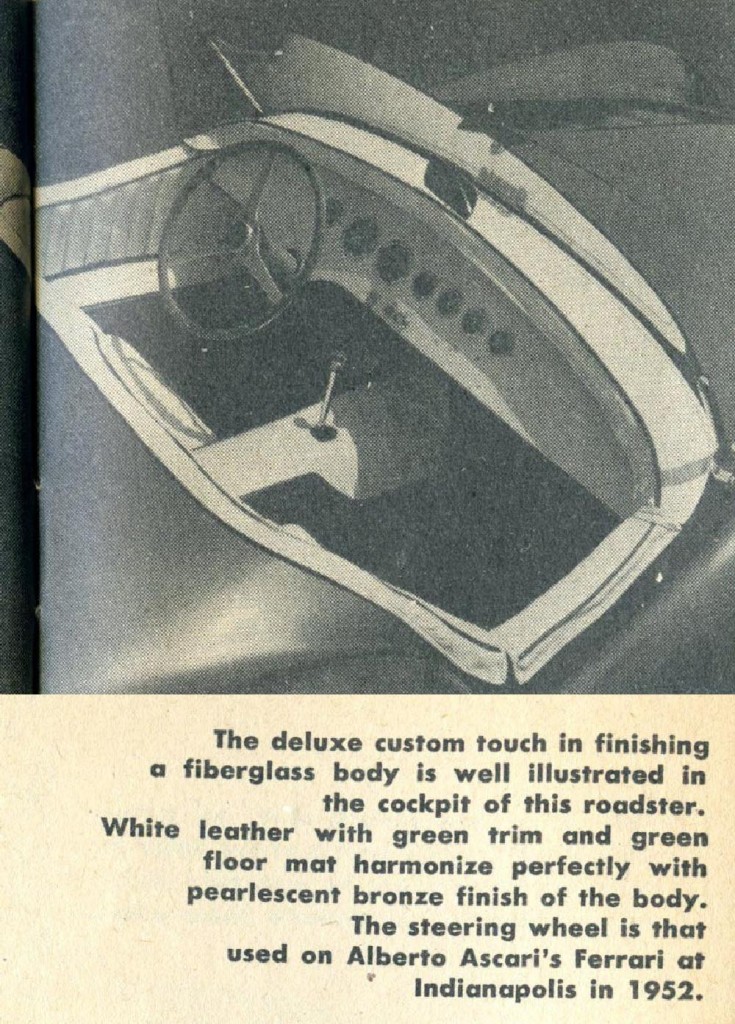

- Interior – white leather with green trim and green floormat harmonize perfectly with the pearlescent bronze finish of the body

- Steering wheel is that used on Alberto Ascari’s Ferrari at Indianapolis in 1952.

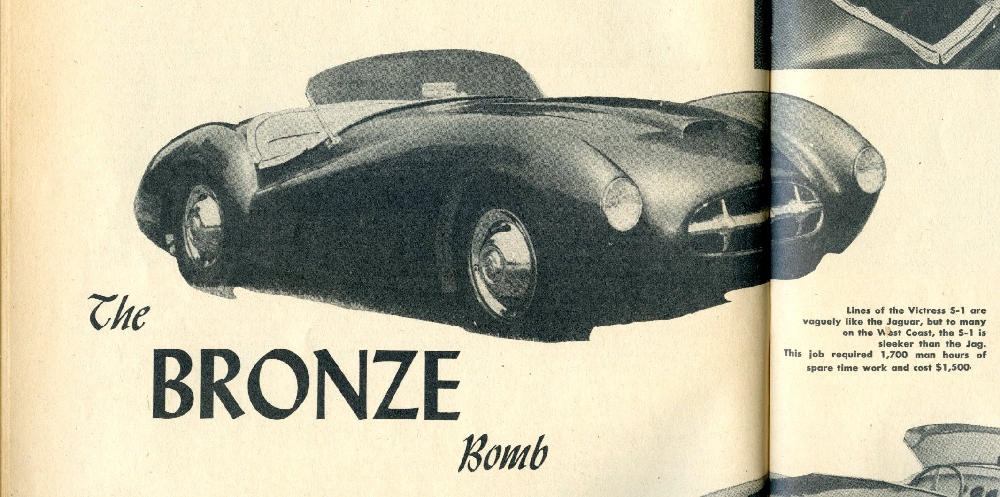

- The build took 1700 man hours to complete

- MacCoon built it on a sprint car tubular chassis

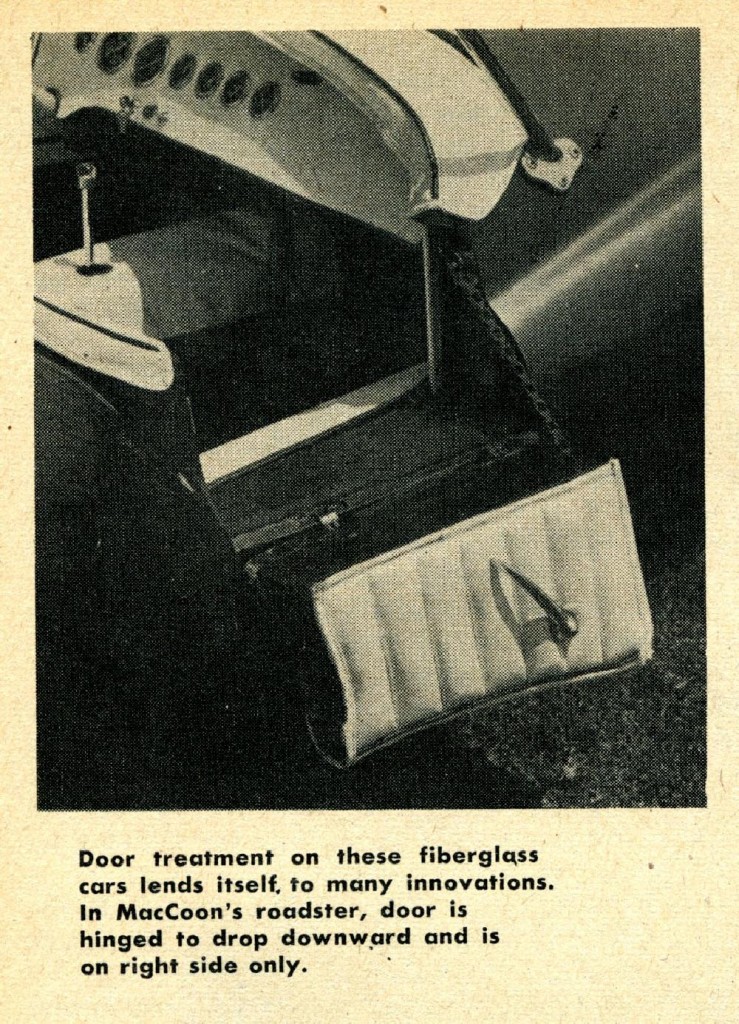

- Interestingly, the doors are hinged to drop downward and his car only had a right side door.

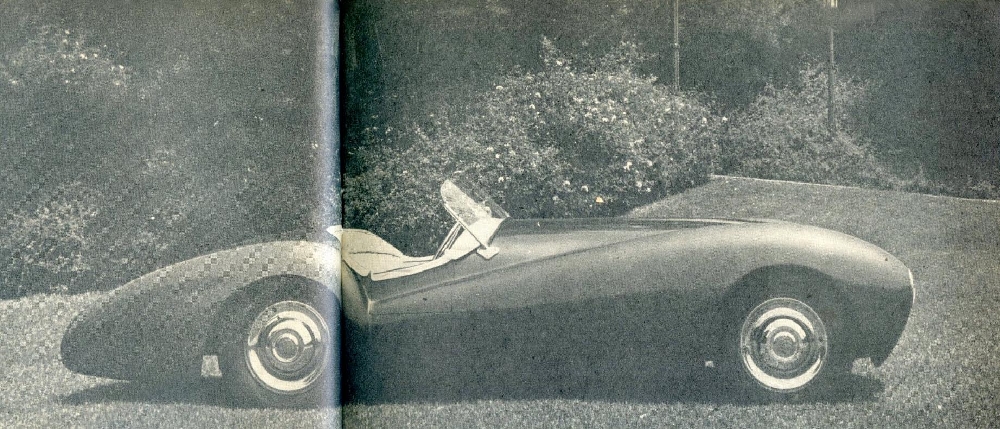

- It used transverse springing front and rear

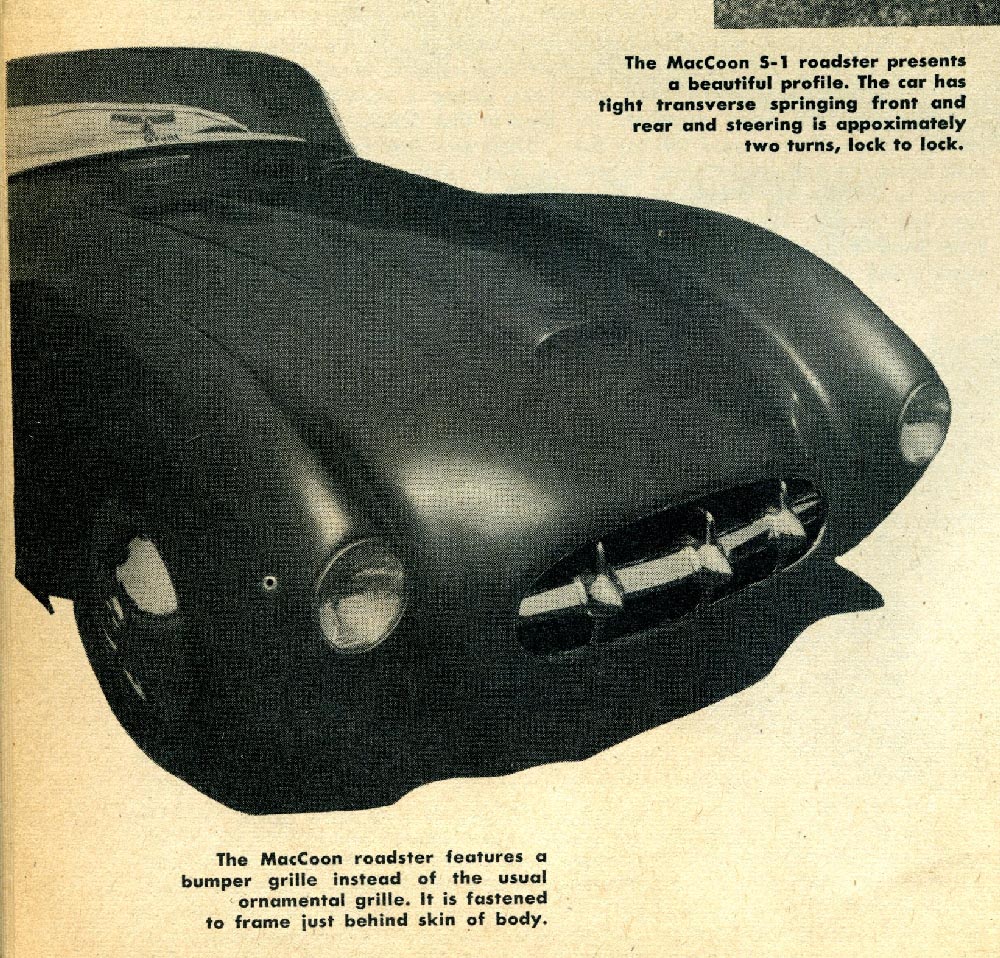

- The front “bumper grille” was fastened to the frame just behind the skin of the body

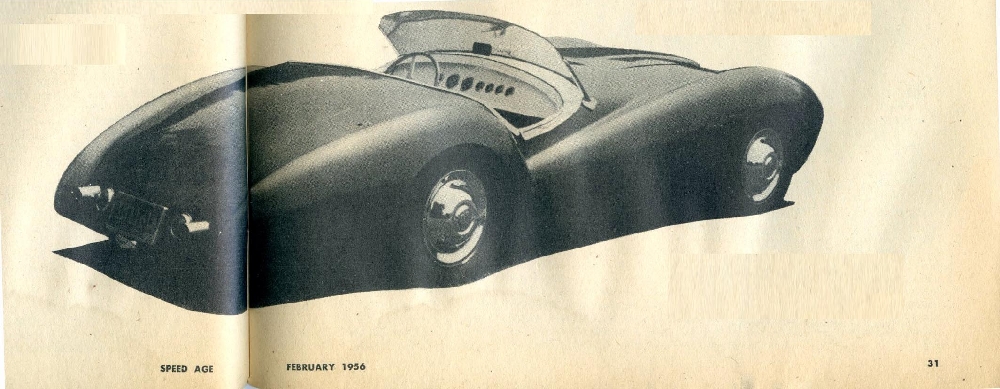

- The body was sectioned to reduce its size to a 96 inch wheelbase (MacCoon used a Victress S1 body and shortened it)

Let’s have a look at what Speed Age Magazine had to say about Dick MacCoon’s car in February 1956:

The Bronze Bomb

Speed Age: February 1956

by Hugh W. Humphrey

Imagine–if you can after reading this–a metallic bronze body with lines smoother than a Jaguar; a cockpit more comfortable than the usual stock passenger car, and a 265 hp. engine capable of 0 to 60 mph. in six seconds and of peeling rubber at 40 mph. in high gear! If you find it difficult to visualize such a combination of glamorized custom job and real hot rod, we’ll make it tougher by adding that this dream car also has the handling characteristics of a European sports model without the usual tricky mechanical problems that come with so many of the imported jobs.

Such a car does exist. In fact, it can be seen roaring through the streets of Los Angeles almost any day and more than one Jag owner has had his ears pinned back when he sneeringly challenged the Bronze Bomb to a “drag” away from a traffic light. With this car, you just don’t do such things.

Young Dick MacCoon, sales manager and trustee of the Grant Piston Ring Company in Los Angeles, always has been a hot rod man. Born into a family where automotive subjects were a topic of conversation at all times, Dick grew up with a wrench in one hand and a Grant piston ring in the other. By the time he had reached his teens, hot rod building was in his blood and he soon became known as a guy with a touch for speed. Among other attributes, MacCoon is blessed with patience, hence the 18 months of work he devoted to building his Bronze Bomb before it was ready for the street.

Dick wanted something different. Since his dream job had to be both a street roadster, dragster and competition road race car, he did quite a bit of calculating before starting work. Having driven European sports cars, he decided that his custom car would have tight suspension and steering to meet such competition. But, he didn’t want to depart from the reliability of our Detroit-made engines and the ease with which replacement parts could be had. Therefore, he broke out the bending jigs and the welding equipment and began construction of a racing spring car chassis which would accommodate a 96 inch wheelbase.

He mounted transverse springs on both front and rear and installed double sway bars for stiffness. It can be added here that the car handles beautifully on the turns with almost no roll or tendency to slide, even at high speeds. Steering linkage was worked out to give a very tight two turns from lock to lock and double Pitman arms lend a hand in this department.

When MacCoon builds a car, he goes all out in every phase of the operation and the engine room is no exception. After the frame and running gear were in some form of completion, he turned his attention to the powerplant. He selected a 1950 Series 62 Cadillac engine which in stock form was rated at 160 hp. at 3800 rpm. with a compression ratio of 7.5 to 1.

First, the engine was torn down and a Weber 3/4 race grind camshaft installed. Since Dick wanted the car for both street use and competition, he was forced to compromise a bit here to obtain the smooth idling which would have been impossible with a full or super grind camshaft. A set of Jahn racing pistons was tied to the top end of the connecting rods.

Further modification of the powerplant included installation of an Edelbrock balanced crankshaft and a completely balanced flywheel and clutch assembly. Magnesium rocker arms naturally replaced the stock Cad items and tubular push rods were added. Next, MacCoon ported and relieved the stock manifold carrying two AAV26 dual throat Stromberg carburetors.

When finished with the engine, Dick had raised the compression ratio from 7.5/1 to 9.25/1 and the horsepower from 160 to 265, checked out on a dynamometer. Best of all, he had the Cad engine capable of turning 6500 rpm. in complete safety.

MacCoon worked up his transmission from a Lincoln Zephyr assembly and installed a ’46 Ford rear end with 3.54 to 1 gear ratio. Rear tires are 7.50 x 16 and rubber on the front end is 6.00 x 16. Returning to the engine room for a moment, Dick added a Bendix electric fuel pump and a Mallory Mag-Spark ignition system.

With chassis ready, a final sentimental touch was added before selection of the body. The Grant Piston Ring Company had sponsored the big Ferrari Grand Prix car driven by the late Alberto Ascari at Indianapolis in 1952. The old red monster yielded its starkly functional steering wheel to MacCoon’s new dreamboat, giving a somewhat stern appearance to that detail.

Dick now was faced with the choice of body styling and construction. He didn’t want the usual hot rod body, cannibalized from all sorts of junk yard odds and ends. He desired something distinctive with racy, sport lines to enclose the pile of dynamite he had assembled in the frame.

In the Los Angeles area, a number of plants had been experimenting with fiberglass auto bodies, particularly for sports chassis. A friend of MacCoon’s, William Boyce-Smith, was (and still is) president and chief engineer of the Victress Manufacturing Company, builders of fiberglass products. Boyce-Smith had been experimenting with a sports car body and after many months research had come up with a design tested and proven in a wind tunnel.

MacCoon decided to use the Victress S-1 body, but found that it would have to be sectioned to fit his 96 inch wheelbase. (Boyce-Smith later reduced the S-1 body dimensions to fit this wheelbase without modification.) A four-inch section of body was removed in the door area and the fiberglass shell rejoined. Then Dick was ready to mount the Victress product on his potent running gear.

Fiberglass is pretty versatile stuff. You can slice it, chop it and drill it without too much trouble, and best of all, if you make a mistake it can be corrected without much trouble. Dick didn’t make any mistakes, but he did do quite a bit of slicing and cutting on his S-1 body. He enlarged the front end air scoop to accommodate a special bumper and grille of his own design and then went to work on the door.

Since the car was to be used in competition, he didn’t want to be bothered with a door on the left side, nor did he want too much fuss and feathers involved on the right. By cutting into the fiberglass about half-way down the normal door height, he worked out a drop-type door of very simple design and operation.

He didn’t bother with a rear trunk, but installed heavy chrome tubing to serve as exhaust tip covers and rear-end reinforcements for the body.

The Bronze Bomb’s cockpit is a practical lesson in what can be done to make an interior both attractive and starkly functional at the same time. MacCoon installed a pair of semi-bucket seats and then trimmed the entire cockpit in green and white leather with a green floor carpet. Foot pedals are real racing type of heavy steel and linkages have been worked out to give a minimum of play.

The Ferrari steering wheel rides at a nice angle to the driver and the instrument panel carries seven Stewart-Warner products. They include a manifold vacuum gauge, tachometer, speedometer, ammeter, oil pressure gauge, water temperature gauge and fuel gauge. The emergency brake lever is a massive piece of steel which looks capable of stopping a locomotive, if necessary.

When painting time arrived, Dick selected a brilliant metallic bronze lacquer and applied the equivalent of about 30 coats of enamel to the fiberglass body. Hand rubbing brought out a luster equal to that obtained on the finest metal paint jobs. You can see “right down” to the undercoat.

Now it was time to test drive the Bronze Bomb and MacCoon eagerly climbed into the cockpit and warmed up the modified Cad engine. He started driving and put the car through all kinds of tests for a 10-hour period. Within minutes, he had looped, skidded broadside, fishtailed and, in fact, experienced every difficulty in the book except flipping.

The Bronze Bomb was hot. Going into a turn at 90 mph., Dick suddenly found he had lost it and the car slid into a field without damage.

However, when the little tricks of handling the car had been ironed out, MacCoon realized that he had a very potent and efficient piece of machinery. But, a little matter of centrifugal force and center of gravity had entered into the picture.

Dick had aimed at an extremely low center of gravity in the job. The Cad engine was dropped to the last fraction of an inch for ground clearance, but in so doing, MacCoon discovered that his center of gravity had become too low.

In rounding a curve at high speeds, the car had a strong tendency to rise on the outer side, away from the usual lift. MacCoon found that a portion of the engine was below the center of gravity line and that it was acting like a pendulum, swinging the car upward on the wrong side. It was necessary to correct this by raising the engine mounting 1 1/2 inches.

Dick MacCoon estimates that the Bronze Bomb cost about $1,500 to build, including body, frame and engine modifications. However, he points out that it couldn’t be duplicated for less than $2,500 or more since he had access to much power tool equipment which cannot be employed by the average car builder.

The Bronze Bomb has been clocked at 135 mph. on the straightaways and if our figuring is correct, the top speed at 6500 rpm. should be about 160 mph., using the 3.54 gear ratio and 7.50 x 16 rear tires. It accelerates easily from 0 to 60 in six seconds, and we had a ride in it when it was peeling rubber at 40 mph. in high gear.

For the hot rodder who is tired of stripped-down bodies, but still wants that power under the hood, a copy of the Bronze Bomb from Los Angeles should fill the bill.

Summary:

What a great car! And the detail shared about this build is extraordinary.

I was a bit amused at the “wind tunnel” reference. While it could be true, I’ve seen this many times with several of the fiberglass companies of the era. What I’ve found is that most of the builders built their own wind tunnels to test the design on a small scale. These men were entrepreneurs and tested all angles, but typically didn’t have a professional wind tunnel for testing their scaled designs (or at least we haven’t found a true example of a full size wind tunnel used on one of these cars yet).

And…good news! I’m on the research path and have found the MacCoon family, and hope to have some new information to share about this special car in the near future – here at Forgotten Fiberglass.

Hope you enjoyed the story, and until next time…

Glass on gang…

Geoff

——————————————————————-

Click on the Images Below to View Larger Pictures

——————————————————————-

I found the statement in the article mentioning magnesium rocker arms interesting. I have never heard of magnesium rocker arms. There are many magnesium alloys, so they must have been an alloy. I don’t believe that rockers of pure magnesium would be strong enough to handle the punishment that rockers take at high rpm. Pure magnesium has about 1/4 to 1/3 the strength of mild steel. A magnesium alloy rocker would not have the strength of a standard rocker. This is the price of performance: lightness vs endurance.

Man is she pretty.. wonder what her fate was.. she would be a hell of a find…

That was a beautiful car—sorry I didn’t get a chance to ride in it. The “wind tunnel” testing was, to put it in Doc’s words, “salesman’s puffing”. I think you could say that the design was “wind tunnel tested” by Joe Mabee at Bonneville in 1953!

Great photos as usual story included..

Mel