| Fiberglass Facts – Home | |||

| Kurtis Sports Car (1949) – Home | |||

| History | Brochures and Advertising | Models Available | Articles |

| Registry and Members Showcase |

Discussion Group | Miscellaneous | Contact Information |

History – By DeWayne Ashmead (Owner of Kurtis Sports Car #1)

Frank Kurtis, the son of a Croatian blacksmith, was born January 25, 1908. At the age of 14 he was apprenticed to Don Lee Coach and Body Works in Los Angeles. This shop specialized in building custom automobiles for Hollywood stars. During his apprenticeship he learned fine metal shaping and welding but in 1919 when Lee purchased Earl Automotive, he was also trained by Harley Earl in the art of body design. By 1926, Kurtis was buying wrecked cars and rebuilding them as custom automobiles, usually sporty open vehicles. In 1930, in the midst of the Great Depression, Kurtis resigned from Don Lee’s operation and started his own shop. He did his first work on a race car in 1933. Over the next few years Kurtis changed his employment several times but he continued to build customized car bodies and race cars wherever he went. In 1937 he went to work for Howard Darrin building Packard-Darrins until Darrin’s pay checks begin to bounce. He then joined a Burbank shop that built race cars. A year later, Kurtis opened his own race shop, Kurtis-Kraft, Inc., and by 1940 was building Indianapolis race cars fitted with Ford V-8’s. Between 1941 and 1943 Kurtis build 128 cars for the Indy 500. Kurtis built cars won every year from 1950 to 1955. He built more than 2/3 of the starting field through 1957. In particular, he built race cars for Ed Walsh of St. Louis until the beginning of the Second World War.

At the conclusion of the war, Kurtis began to make midget race cars which propelled him to the zenith of his career. He built approximately 550 assembled midget racers and another 550 kits, designing a rigid tube frame chassis with softer springs for better traction. His theory, which later proved to be correct, was the closer the wheels followed the driving surface, the better the traction and the faster the car could negotiate a turn before centrifugal force pulled it out of control. He also found that reducing unsprung weight allowed the wheels to better follow the surface. A new torsion bar replaced the quarter-ellyptic springs on the front. It could be adjusted for different track conditions and significantly improved handling. Kurtis’ shop specialized in frames and bodies and sourced steering, engines, axles, etc. from others.

At the conclusion of the war, Kurtis began to make midget race cars which propelled him to the zenith of his career. He built approximately 550 assembled midget racers and another 550 kits, designing a rigid tube frame chassis with softer springs for better traction. His theory, which later proved to be correct, was the closer the wheels followed the driving surface, the better the traction and the faster the car could negotiate a turn before centrifugal force pulled it out of control. He also found that reducing unsprung weight allowed the wheels to better follow the surface. A new torsion bar replaced the quarter-ellyptic springs on the front. It could be adjusted for different track conditions and significantly improved handling. Kurtis’ shop specialized in frames and bodies and sourced steering, engines, axles, etc. from others.

The demand for Kurtis midgets became so great that dealers were set up. Ed Walsh, who had raced at Indianapolis in a Kurtis-built car, became one of the dealers in St. Louis. He would take delivery of a new chassis and then finish it with paint, chrome, and upholstery and install the engine. Walsh visited Kurtis in California and proposed a partnership in 1947 to build both race cars and sports cars. It was not a good move for Kurtis. According to his son Arlen, Frank Kurtis was a talented and likeable guy but a very poor businessman. Walsh had promised to finance the new venture which was spun off from Kurtis Kraft and named Kurtis Sports Cars, Inc. Walsh never brought the promised funds to the table, leaving the struggling company grossly undercapitalized. Walsh considered the partnership a hobby whereas Kurtis depended on it for his livelihood. The partnership was dissolved in 1955.

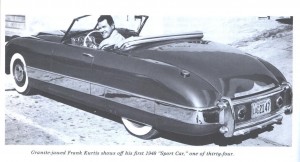

Following the formation of the partnership with Walsh, Kurtis started to develop a sports car that according to Ford Times, would rival the “challenge of the foreign sports cars…” He customized a 1941 Buick which he converted into a two passenger sports car that he drove to Indianapolis in 1948. According to an article in the October, 1948 issue of Merchanix Illustrated, this car became the basis for his sports car. Everyone was excited about it and encouraged Kurtis to put it into production. Benson Ford, in particular was so impressed that he instructed the Ford Warehouse in California to supply Kurtis with whatever Ford parts he needed. Tom McCahill of Mechanics Illustrated wrote of the prototype, “It has speed, safety, luxury, and dazzling class.” Veteran racer, Bud Winfield reported to Hot Rod Magazine in February 1949 that the Kurtis Sports Car had “remarkable handling characteristics that may well compete with that of foreign sportsters.” The wheelbase was 100 inches and the tread 56 inches. It was only 48 inches tall and 170 inches from bumper to bumper.

A Stewart-Warner instrument panel with a full array of gages including a tachometer, adjustable leather bucket seats, plexiglass side curtains, floor gearshift and a Warner Gear overdrive were all standard equipment. Both the hood and rear deck lid were opened from inside the car. The 239 cid Ford V-8 engine was modified using Edelbrock heads, Spaulding dual ignition, Offenhauser intake with two Stromberg carburetors, a hotter camshaft and Fenton exhaust headers. The pistons and crankshaft were sourced from Mercury engines. The bore was 3 5/16 inches, the stroke 4 inches and compression 10.5:1. A Ford truck oil pan was used because it held an extra quart of oil. Most of the cars had a Ford truck differential housing which was much stronger than the automobile unit in order to withstand the greater torque of the modified engine. Although 95% of the car was sourced from stock production-car items, they were carefully packaged for maximum  performance. As with his race cars, Kurtis saw to it that all of the chassis factors – spring rates, shock absorber settings and weight distribution – were attuned to maximum road holding and performance. For example the car has 4 wheel independent suspension with a transverse spring in the front which gives a softer ride without compromising handling. The car had a bumper grill mounted on the frame horns via rubber shock absorbers. A chrome rub rail extended around the body, protecting the sides as well as the front and back. The December 1949, issue of Ford Times wrote, “In designing the body of his car, Frank Kurtis followed the prevailing American fine car tradition: there is no trace of a fender contour, front or rear. The wrap-around bumper really wraps around the whole car! He used Ford suspension to get a velvet-smooth ride and the car was designed for a Ford or Mercury V-8, offer stock or speed shopped.”

performance. As with his race cars, Kurtis saw to it that all of the chassis factors – spring rates, shock absorber settings and weight distribution – were attuned to maximum road holding and performance. For example the car has 4 wheel independent suspension with a transverse spring in the front which gives a softer ride without compromising handling. The car had a bumper grill mounted on the frame horns via rubber shock absorbers. A chrome rub rail extended around the body, protecting the sides as well as the front and back. The December 1949, issue of Ford Times wrote, “In designing the body of his car, Frank Kurtis followed the prevailing American fine car tradition: there is no trace of a fender contour, front or rear. The wrap-around bumper really wraps around the whole car! He used Ford suspension to get a velvet-smooth ride and the car was designed for a Ford or Mercury V-8, offer stock or speed shopped.”

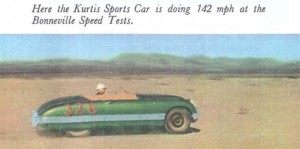

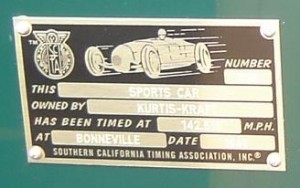

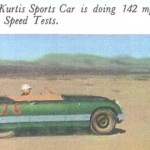

On August 27, 1949, Wally Parks, editor of Hot Rod Magazine, was clocked at 142.51 mph at the Bonneville Salt Flats driving a green Ford powered but Edelbrock built Kurtis Sports Car which later was certified as being this car (KB003). Jaguar had set a land speed record for sports cars of about 134 miles per hour. Frank Kurtis wanted to better this. He took the only production car ever painted green, and had Bobby Meeks, the engine builder for Edelbrock “stroked” the engine and installed two Stromberg 97 carburetors on an Offenhauser intake manifold and Edelbrock heads. A duplicate engine produced 380 hp on the dyno. A pressurized fuel tank was installed in place of the passenger seat and used the same bolt holes to mount it. The original car had belly pans.

Before setting his record, Parks ran two qualifying runs, one at 128.57 mph and the other at 131.19 mph. After the first run Parks learned that the car had an overdrive which would allow him to get more speed while running the engine at a lower rpm. His later runs reflected the use of the overdrive. His fastest speed was 143.08 mph down and 141.95 mph return for the average speed of 142.515 mph. Known as the Kurtis-Kraft, it was the only sports car that ran at Bonneville in 1949. According to Greg Sharp, Dean Batchelor also drove this Kurtis Sports Car over 140 MPH on the salt flats after Parks wet the record.

Wally Parks remembered that run years later. He said that Kurtis, had initially installed a marine tachometer drive that read the engine speed at half of the true speed. Bobby Meeks told Parks to keep the RPM?s at about 6000. When Parks returned to the pits he reported that he could only get 3500 RPM?s out of the engine. It was at this point Meeks realized that the tachometer drive was wrong and the car had actually run at 7000 RPM during the record run.

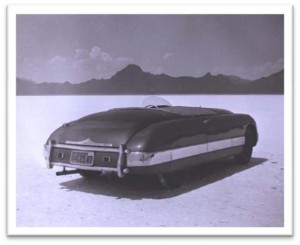

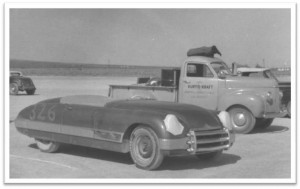

Prior to the Bonneville run for the land speed record, the car was taken to Rosamond Dry Lake in California for a shakedown run. Kurtis was able to push it to 130 mph which was just short of the speed record set by a Jaguar earlier that year. It was “captured” in a photograph taken by Lyle Allen while at the dry lake. It carried the number 326 on its rear quarter which was the same number it had when it made the Bonneville run. When it ran at Bonneville Dean Batchelor took several photographs of that record setting event.

Prior to the Bonneville run for the land speed record, the car was taken to Rosamond Dry Lake in California for a shakedown run. Kurtis was able to push it to 130 mph which was just short of the speed record set by a Jaguar earlier that year. It was “captured” in a photograph taken by Lyle Allen while at the dry lake. It carried the number 326 on its rear quarter which was the same number it had when it made the Bonneville run. When it ran at Bonneville Dean Batchelor took several photographs of that record setting event.

Following the record setting run at Bonneville Salt Flats, John R. Bond of Road & Track reported that he believed it would outhandle a Jaguar XK-120. Tom McCahill of Mechanix Illustrated reported that the car was “far more comfortable than most foreign cars and takes the bumps smoothly.” Motor Trend said the Kurtis Sports Car had “all the features a sports car should have: Speed, maneuverability, acceleration, power and sleek looks.”

Each car was hand built. In the first cars the fenders, hood and trunk lid were fiberglass and were made by Paul Ohmohundro in Paramount California. Each front fender cost $14.56 in materials compared to $3.00 for the same fender in steel. The difference in material cost was more than offset by the saving in labor where limit production is expected. Nevertheless, the fenders of the later cars were produced out of stamped steel. The cowl rear deck and dash were cast aluminum. And finally, the doors were steel. The kit was priced at $1,495 and a complete car at $3,495. Two models were offered. The standard model had regular Ford automobile gages placed in the dash. The deluxe model utilized Stewart Warner gages in an instrument cluster. The leather interior was designed and installed by Chet Miller who had an upholstery shop in Glendale, California near Kurtis? facility.

The Ford engines put in the cars were crate engines. With engine modifications, etc. the final price could approach $5,000 for a deluxe model such as this is. Besides the two prototypes, there were 16 finished cars, 2 kits, 15 partially finish Muntz cars, and 10 bare chassis produced for Muntz in Glendale by Kurtis. (Number 16 (serial number 18)of the finished Kurtis cars was made for Arlen Kurtis, Frank?s son and given to him upon graduating from high school. Number 18 was the last Kurtis Sports Car made.) The first production car carried serial number KB003. It was titled to Kurtis Kraft and kept for several years as a promotional vehicle. During the company?s ownership Kurtis? partner in the sports car venture, Ed Walsh, frequently drove the car leading to the mistaken belief that he actually owned it. Harry Birdsall in Hartsdale, New York actually purchased the car from Kurtis Kraft. He went out to California, picked the car up and drove it back to New York. Birdsall subsequently painted the car yellow. Shortly thereafter he moved to southern Florida. He kept the car for about 4 years during which time he raced the car extensively.

The Ford engines put in the cars were crate engines. With engine modifications, etc. the final price could approach $5,000 for a deluxe model such as this is. Besides the two prototypes, there were 16 finished cars, 2 kits, 15 partially finish Muntz cars, and 10 bare chassis produced for Muntz in Glendale by Kurtis. (Number 16 (serial number 18)of the finished Kurtis cars was made for Arlen Kurtis, Frank?s son and given to him upon graduating from high school. Number 18 was the last Kurtis Sports Car made.) The first production car carried serial number KB003. It was titled to Kurtis Kraft and kept for several years as a promotional vehicle. During the company?s ownership Kurtis? partner in the sports car venture, Ed Walsh, frequently drove the car leading to the mistaken belief that he actually owned it. Harry Birdsall in Hartsdale, New York actually purchased the car from Kurtis Kraft. He went out to California, picked the car up and drove it back to New York. Birdsall subsequently painted the car yellow. Shortly thereafter he moved to southern Florida. He kept the car for about 4 years during which time he raced the car extensively.

According to Frank Kurtis, KB003 was suppose to be powered by a Studebaker V-8 motor. Consequently the first production car (KB003) had a 1949 Studebaker Champion differential and a modified 1948 Studebaker Champion front axle. The wheels were also Studebaker Champion wheels as were several other parts including the steering box. When the Studebaker engine failed to materialize, Kurtis accepted Bensen Ford’s offer and installed the Ford flathead engine, transmission and other parts in car number KB003 but retained the Studebaker suspension, differential and wheels, etc. because the car was partially build and awaiting the Studebaker engine to complete it. (Later cars use Ford suspensions, differentials and wheels.) The car was originally painted green with tan leather interior and tan top which was padded. Over its life in addition to the green color it has been painted white, black, purple, brown, and yellow.

Champion differential and a modified 1948 Studebaker Champion front axle. The wheels were also Studebaker Champion wheels as were several other parts including the steering box. When the Studebaker engine failed to materialize, Kurtis accepted Bensen Ford’s offer and installed the Ford flathead engine, transmission and other parts in car number KB003 but retained the Studebaker suspension, differential and wheels, etc. because the car was partially build and awaiting the Studebaker engine to complete it. (Later cars use Ford suspensions, differentials and wheels.) The car was originally painted green with tan leather interior and tan top which was padded. Over its life in addition to the green color it has been painted white, black, purple, brown, and yellow.

Following its run at the Bonneville Salt Flats, the car was returned to Glendale where Kurtis removed the high performance engine and replace it with another Ford 8 AB flathead engine that was more “streetable.” The original engine was slowly stripped of its speed equipment for other projects. Arlen Kurtis owned the last Kurtis Sports Car and used the pistons, rods, crank and cam from that engine to enhance the performance in his own car.

While racing in the Kurtis Sports Car purchased from Kurtis Kraft Harry Birdsall ultimately overheated the engine and destroyed the motor. The car was subsequently sold to a man in Colorado. In approximately 1954, a Cadillac engine was installed in the car by this man, in an attempt to emulate the Muntz Road Jet and increase the performance of the car. It was licensed in Colorado as a 1954 Cadillac because the State regulation required it be titled and registered as the same car as the engine. A technical editor of Road & Track wrote, of the car following the installation of the Cadillac engine, “I must admit I?ve never been shoved back into the seat quite so hard. The driver was a man of no little sports car experience and he swears it handles better than a Jaguar XK – 120… I am inclined to agree.”

The second owner drove his car until the late 1950’s when he wrecked it. The windshield was destroyed as was the hood and rear deck lid. The left rear quarter and right front quarter were also damaged. In 1960 Albert Carleno of Littleton, Colorado purchased the wrecked car. He kept it four years during which time he tried to repair it. He then sold it to Elizabeth Deering who kept the car about ten years. She then sold it to W.D. Cowan Auto Sales in Manhattan, Kansas. This dealership owned the Kurtis for about a month before selling it to Ray Stall in Davenport, Iowa in April of 1974. Stall believed he could restore the car but in August of that same year he died. Title to the car passed to Stall’s mother Genevieve K. Cowan, also of Davenport. She immediately sold it to Charles Lee Treeway of Bettendorf, Iowa. It was still unrestored and Tredway believed he could do the job. Pictures taken of the car at the time show that the passenger side

The second owner drove his car until the late 1950’s when he wrecked it. The windshield was destroyed as was the hood and rear deck lid. The left rear quarter and right front quarter were also damaged. In 1960 Albert Carleno of Littleton, Colorado purchased the wrecked car. He kept it four years during which time he tried to repair it. He then sold it to Elizabeth Deering who kept the car about ten years. She then sold it to W.D. Cowan Auto Sales in Manhattan, Kansas. This dealership owned the Kurtis for about a month before selling it to Ray Stall in Davenport, Iowa in April of 1974. Stall believed he could restore the car but in August of that same year he died. Title to the car passed to Stall’s mother Genevieve K. Cowan, also of Davenport. She immediately sold it to Charles Lee Treeway of Bettendorf, Iowa. It was still unrestored and Tredway believed he could do the job. Pictures taken of the car at the time show that the passenger side  and rear decks have had major work done to them and were in primer.

and rear decks have had major work done to them and were in primer.

The windshield, rear license plate guards, and chrome Kurtis logos that should have been on the hood and deck lids were missing. The condition of the interior at that time is unknown. After unsuccessfully trying to obtain a new windshield for almost twenty years, he sold it to Marline Earl Weakly of Moline, Illinois on July 1, 1993. Weakly plagued with macular degeneration commenced a serious restoration project beginning with the replacement of the Cadillac engine, with a 1949 Ford flathead engine without speed equipment. He painted the car yellow and installed a white interior. For the next ten years, he continued to search for a windshield and the hood and trunk medallions. He wanted to show the car in AACA competition but never did.

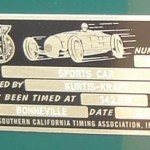

Finally, in February of 2004, Weakly admitted defeat and sold the Kurtis to an automobile broker, Mark Hyman, Ltd. of St. Louis. This company then sold the Kurtis to H. DeWayne Ashmead in March of 2004. Ashmead completely restored the Kurtis including reinstalling the original speed equipment on the Ford engine. The car has been certified by Arlin Kurtis as being the record setting Kurtis Sports Car. Further Wally Parks, at the age of 94, signed the glove box door of this car next to the Bonneville Speed tag which was issued by SCSA in 1949. This is the only car he has ever agreed to autograph.

Official records state that 34 Kurtis Sports Cars were built. Eighteen, including the two prototypes, were finished by Kurtis in his Glendale facility. Two additional cars were kit cars and the rest were built to Muntz’s larger specifications. Earl Muntz had previously purchased the custom Buick that had served as the basic design for the Kurtis Sports Car. He subsequently purchased two additional cars which he resold. Muntz was entranced with the design and in late 1949 offered Kurtis $75,000 for the rights to the car and the tooling. He paid for this in early 1950. Following the sale, Kurtis built ten bare chassis for Muntz which figured into the 34 total cars built. Muntz added a rear seat, much to the chagrin of Kurtis. He used all steel panels and powered the heavier car with either Lincoln V-12 or Cadillac V-8 engines. Kurtis, who originally served as a consultant, resigned and criticized the increased size, weight, and the very poor workmanship of the Muntz Road Jet, as it was called. Muntz built 394 cars, loosing $1,000 on each one before he shut down his Illinois facility.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.