Note: This is the first in a series of stories about the fiberglass sports cars that appeared in the 1954 Custom Cars book by Motor Trend. Click here to review each of these stories on Forgotten Fiberglass.

————————–

Hi Gang…

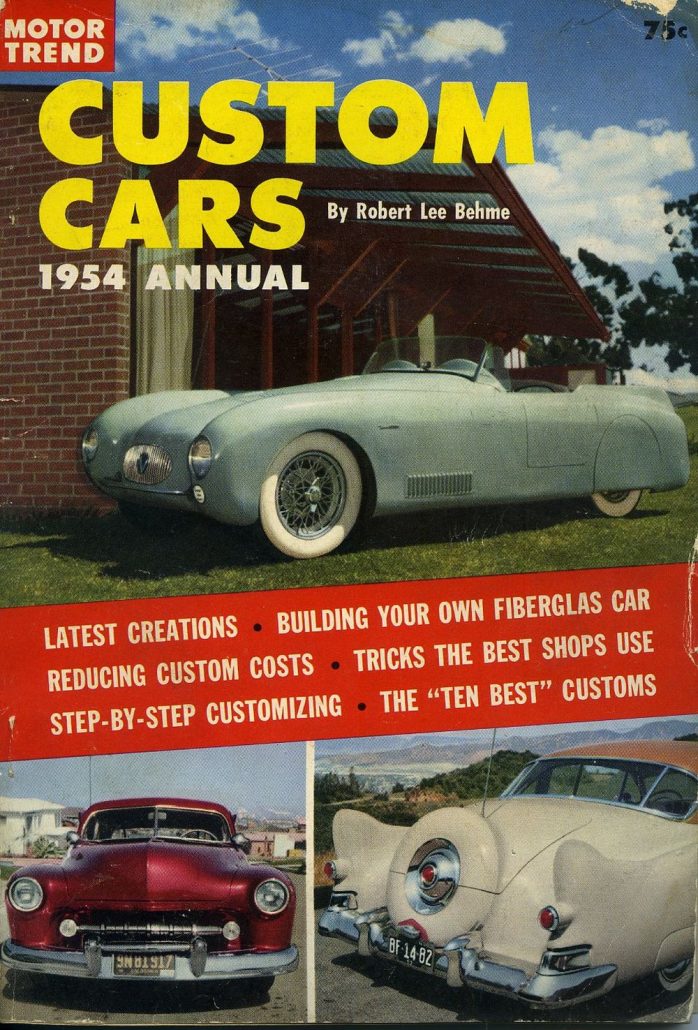

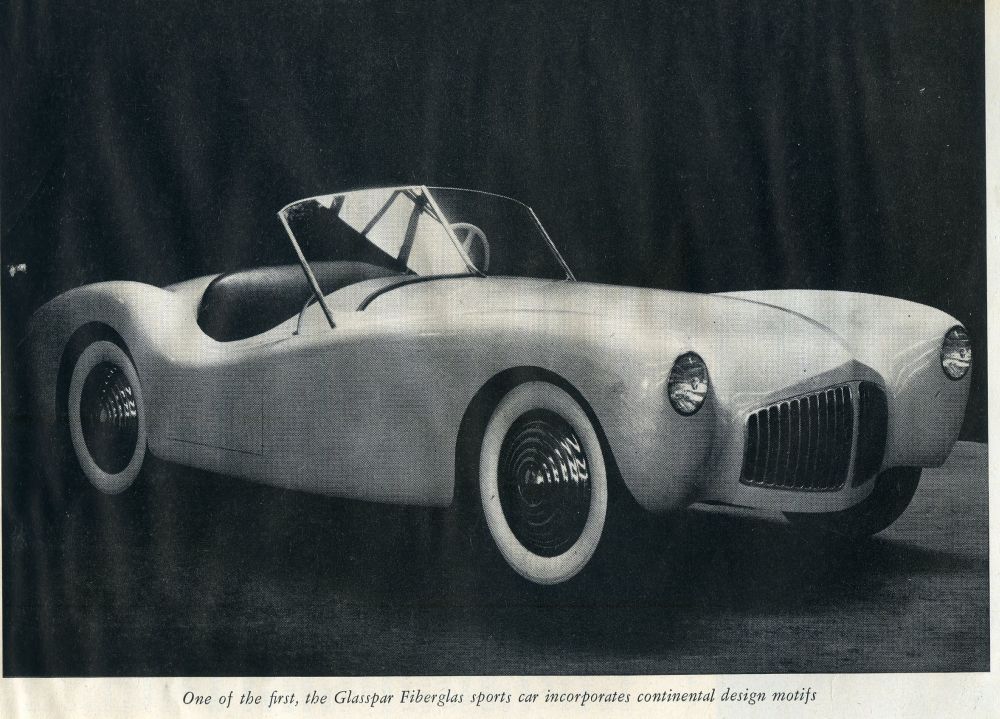

This is an excellent review of the history of fiberglass – just three years after the debut of fiberglass sports cars in America at the November, 1951 Petersen Motorama in Los Angeles, California. And this book – Trend Book 109 on “Custom Cars” was released in the same year as the 1954 Trend Book 112 titled “Manual of Building Plastic Cars.” It may have been the precursor to the release of book #112 but either way it contains some great information and photos not seen anywhere else.

Given that this article is 18 pages long, I’ll be dividing up the article in about 10 or so “parts” and discussing each of those “parts” over the course of the next several weeks. This will make it more digestible for everyone to read. And…it allows us to focus on one aspect or car marque at a time. Our first article in this series focuses on the author’s introduction of fiberglass to his readers. And it’s interesting to note that even in 1954, he was using the word “spaceship” to describe the futuristic and high technological aspect of fiberglass in the public’s view.

Other things of interest is the way in which the author describes how Detroit rejected the styling interests of the public in the early 1950s, and that American’s looked toward Europe for their styling cues. It’s nicely written in this manner and topic and I think you’ll enjoy reading it.

So…away we go!

1954 Custom Cars Trend Book 109

The Facts About Fiberglass

Many Americans remember the 1930s very well. They were years which were black in the memory of many, for they were hard years. Throughout the country business was bad. There was a depression. People without money were trying hard to save a buck. There was no room for new ideas because the old ones were hard to sell. New products were looked upon with suspicion. They were considered inferior substitutes: despised ersatz. Traps for the poor.

It was into this era of skepticism that a handful of scientists brought their newest dream: a dream made up of millions of tiny particles of glass. Made up of glass though it was, their dream was a strong dream given tremendous strength by the application of a polyester resin which bound the glass fibers into a material stronger than steel. These men had a great belief in their product and saw thousands of new uses for it in the bright world they believed just around the corner.

Unfortunately, their dream received little interest when it made its debut 17 years ago. Few saw any commercial possibilities. The public thought its claims fantastic. Fiberglas was some foreign material from some unknown planet. “Use it for building rocket ships and space helmets,” many suggested.

It as through the continued faith of the dreamers, people in firms such as Owens-Corning, that kept the product alive. Owens-Corning called their product “Fiberglas” and the name became the by-word for the “spaceship” material, but even with the public’s acceptance of the name, the glass fiber plastics were not wholly accepted.

In fact, it was not until 1936 that plastics received their first public plug. That year Henry Fiord picked up a heavy sledge hammer and took a healthy swing at the turtle deck of his experimental soy-bean plastic auto.

The echoes of that swing made newspaper copy for several months. But when the car failed to materialize, the stalling convinced John Q. that plastics were only for trips to the moon.

Plastics for automobiles might have been completely forgotten had not someone remembered the glass fiber plastics. Until this time Detroit had hesitated because plastics were considered impractical. They were not adaptable to current production line methods. However, since Fiberglas was different from other plastics, some engineers felt it had possibilities.

Between 1936 and 1940 several automotive engineers wrestled with the problem. They built experimental cars which received a lot of publicity but they failed to lick the mass production problem. Like the forerunners, their cars failed to ever reach the public.

Stout Scarab

Around 1940 a car arrived on the American automotive scene which, for a while, seemed destined for success. The car was designed from the chassis up for plastics production. It was called the Scarab, and was a radical new automobile for its time. Designed by William B. Stout, it featured rear engine drive and “lounge” type seats. It was literally a plastics car from bumper to bumper, but somewhere the dream went astray. Perhaps it was its radical design or perhaps this time the public was not ready to take plastics seriously.

During the war America was re-introduced to plastics. This time the introduction was more acceptable. Metal supplies were scarce. Imports of critical ore were low. Many important war items and certainly most civilian products were forced to convert to plastics or cease production.

At first the thermo-plastics, the heat-molded plastics, were most popular. Gradually the flood of plastic housewares broke down the public’s reserve. The material began to become accepted. For a time it seemed as if all plastics had made a successful intrusion

In some fields plastics did become industrially acceptable, carrying over their war time popularity to build a new post war industry, but this was not the case in Detroit. Once metal was again plentiful the major companies turned their backs on the potential of plastics. Metal, although limited in contour designs, was easy to fabricate in simple shapes. On a production line basis, Fiberglas was virtually an unknown quantity with many serious problems to iron out.

At once the heavy presses of the auto factories began stamping out steel bodies for a public which had been without cars for four years. The pleasing rhythm of the huge presses meant profit. Detroit could see no advantage in a change.

The New Trend

By the end of the war, Detroit products were selling to an unchallenged market. But a new kind of buying public was being born. Many of the G.I.s had gotten their first glimpse of European autos during the war and they began to dream of the more advanced stylings they’d seen on the continent. In a few short post-war years the American public suddenly grew up. It came of age and became car conscious. The younger drivers spear-headed a demand for better craftsmanship and greater engineering skills. They demanded both the economy car and the sports car. All over America the cry arose for more quality and better roadability.

For some reason, at a time when vast new markets seemed possible, Detroit suddenly became deaf. It refused to listen to the buying public but the foreign producers who had coveted the American market from across the Atlantic Ocean heard the noise.

They felt out the market through the import of luxury cars: the Bentleys, Rolls Royces and Jaguars. When these cars sold, the lower priced cars began to arrive: the Hillmans, the Austins, the MGs and the Renaults began taking business away from Detroit. At this point it is possible that Detroit’s earache became a disquieting headache.

By this time the men who kept faith with the “space ship” plastics began to see opportunities to make their dreams become a reality. They began to see a definite market for their product.

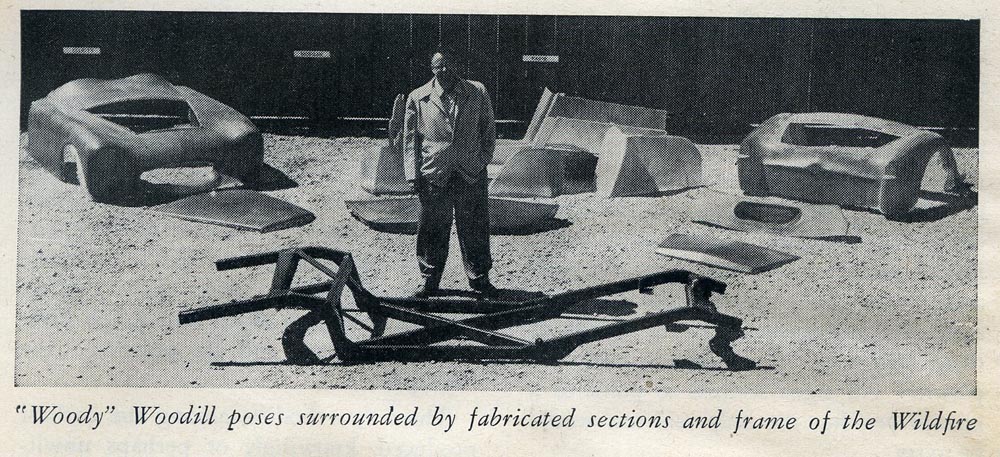

The greatest handicap in the use of glass fiber plastics had been a lack of production methods which would work without extensive changes. If plastic was going to work in the immediate future, these men knew the solution would have to involve slow handmade production methods. Each body would have to be fabricated by hand. The dreamers began to become the realists as they examined the new automobile public.

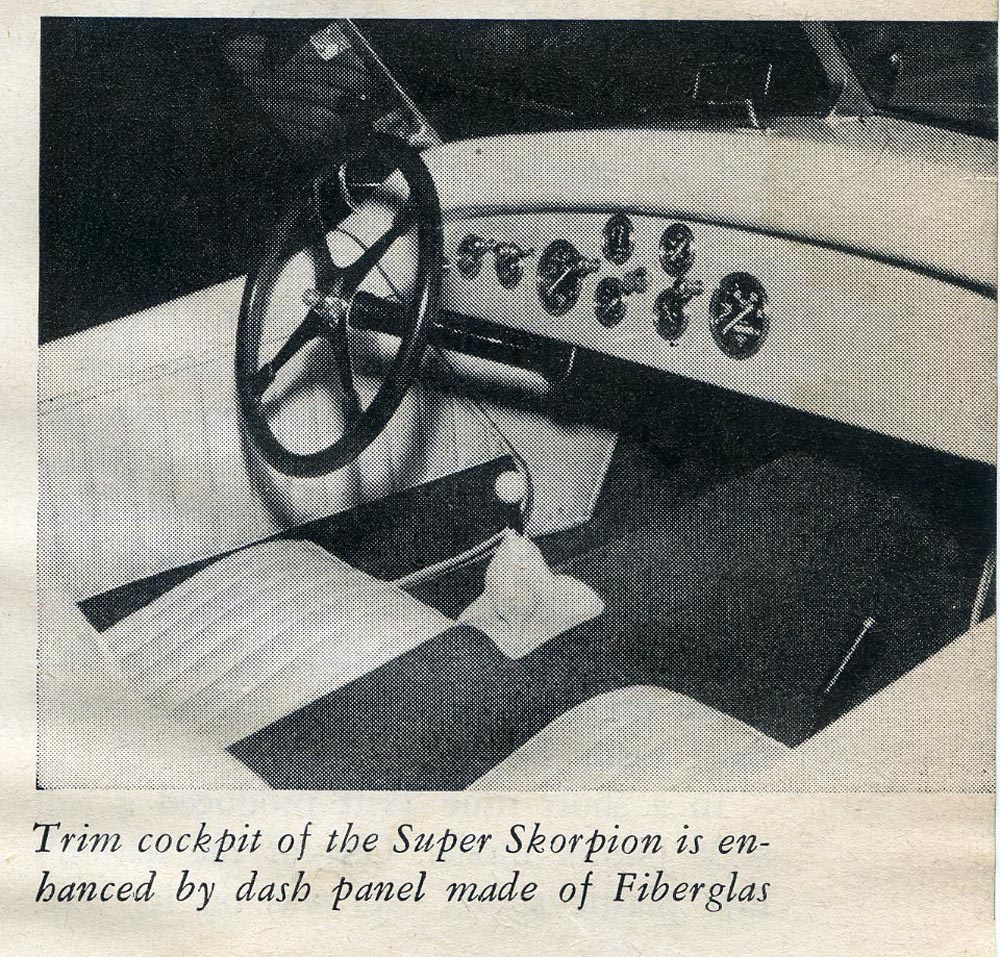

Customized autos were making a strong bid for recognition. It seemed to these men as if the handmade quality of the primitive plastic construction could be the strong sales point. No expensive molding or presses would be necessary. Each auto owner could actually have a custom auto.

The big question in the minds of these men was: “Is the public ready for plastic?” All signs seemed to point to an answer yes, but the only real test would be to try.

Summary:

Even though this appeared in print back in 1954, there were a few errors. For example, the reference to Henry Ford and the first fiberglass car was mostly true – but the “trunk” was the only plastic part on that first car.

The Scarab car he mentioned appeared in the postwar years – 1946 – not before, and there are some other minor errors too, but all in all an excellent article that is spot-on concerning the feeling of how and why “fiberglass” would become a hot topic for custom builders and individuals who had the talent to design and build their dream.

Hope you enjoyed the story, and until next time…

Glass on gang…

Geoff

——————————————————————-

Click on the Images Below to View Larger Pictures

——————————————————————-

Since Geoff and Rick have miraculously dusted off so many of us who were involved in the 50s fiberglass sports car design, fabrication of coachwork . . . they sparked an interest in that era to others by their effective employment of electronic media and concours participation. Many other folks are strongly attracted not only to the history of this era, there are people now who are finding and restoring these vehicles that represent how individuals and small groups were successful in creating highly personalized sports cars without the stereotypical complexities of automobile manufactuters who ‘knew’ what we wanted, but never ‘asked’.

Kudos to the people who have and who will respond here in the ‘comment’ gallery. Who better to help provide individual styles/formats for our histories that represent our merging of aesthetic and engineering prowess during this era of enlightenment ? Rick and Geoff have certainly understood this. Consider, too, at the outset of their “Forgotten Fiberglass Sports Cars of the Fifties” endeavor, that they have ‘asked’ us to share our motivations and descriptions of our very personal glassfibre transports of delight . . . . . . . .

PS : I too, Guy Dirkin . .” . look forward to the rest of this series. . .”

Wasn’t there a more or less ‘grass roots’ grievance against fiberglass cars

from the steelworkers ? A member of the House of Representatives and his

family lived next door to us in Pennsylvania. I recall hearing conversations regarding this issue, but don’t remember specifics, except that that the manufacturing technolgy at that time was incapable of producing the neccessary cooachwork volume . . . .

Some people who are on both the Sprite Midget and Arcane Auto lists just found and saved the molds and tooling for the Arkley conversion to BMC Spridgets in San Diego. This kit could turn a post Bugeye Sprite into a proper looking Brit roadster with tones of Morgan and Lotus… I can’t fit in one, but they look cool…..

http://www.arkleyss.com/oldsite/

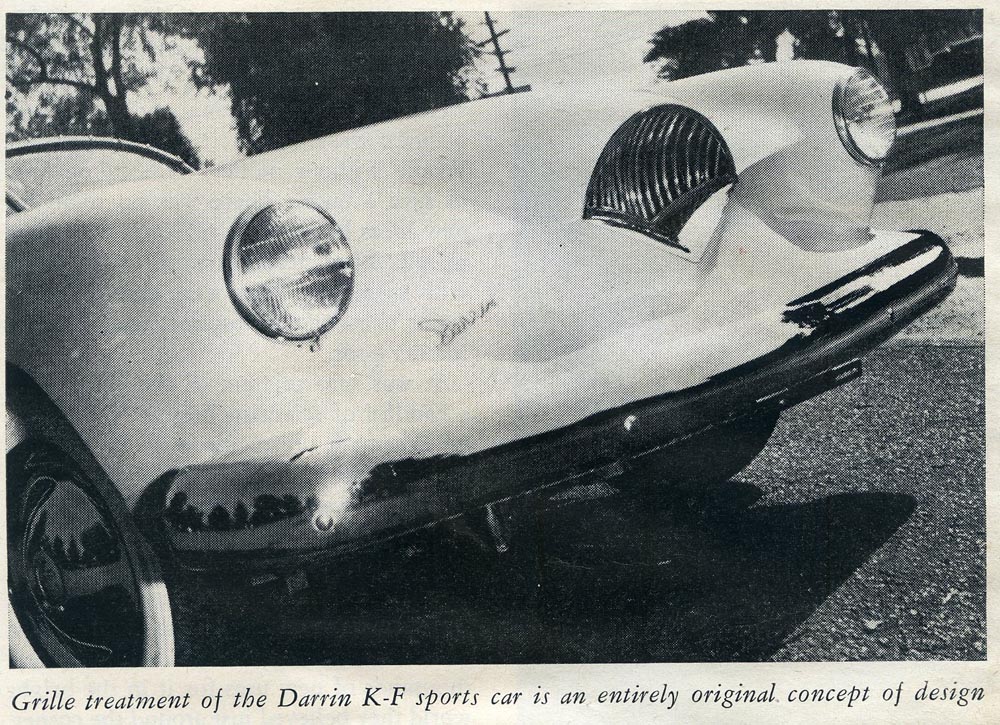

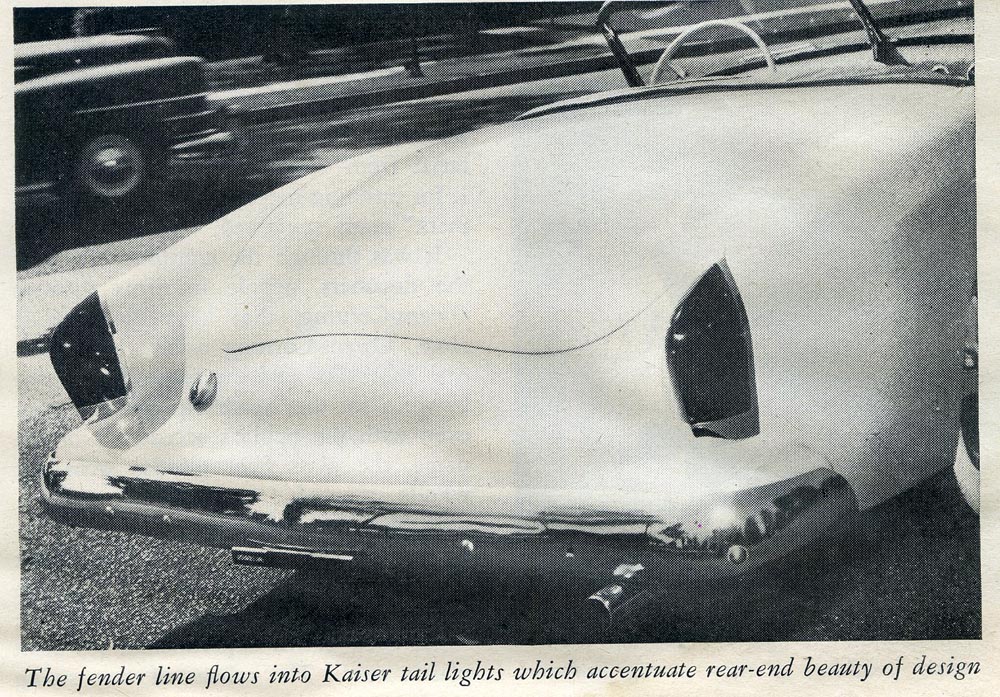

I remember these little car magazines well. My mother says that i learned to read early because I wanted to know what the copy was, not satisfied with just looking at the pictures. I loved cars, the more unusual the better. While friends were collecting comic books, I had a shelf full of these half-sized custom car publications. Hot Rod and Motor Life were OK, but I was not into racing or new car features. It was custom cars for me!!! Plastic was the Sputnik of automotive materials and the sky was the limit! The first Corvettes were amazing and the Kaiser Darrin, with its sliding doors and landeau iron activated top, trumped the T-bird and were the only thing that came along that could rival the Jag XK120, arguably the prettiest car ever made. Living in California allowed me to see many of these cars on the street in the flesh. Though I have never owned a ‘glass car, I have followed them since childhood. I consider FF today’s cyber little magazine and love to read about these cars again.

Very interesting. 1) The readiness of the public to accept plastic products, in general, is important. Once you start using plastic buckets at least the public can relate in some way to even the notion of a plastic car body. 2). Detroits avoidance of the use of plastic can be argued from a production run standpoint. Detroit was interested in cars that coul be produced in tens of thousands. GRP could not accommodate that business requirement. 3). The use of GRP for sportscar an racing car bodies is logical. Actually, once GRP was available, it was illogical to build a sports or race car body from anything other than composite. Going back to point one, plastic became synonymous with cheap. It would be a while for a GRP Ferrari …because of the perception of the Ferrari buyer. The new (2013) Aston Martin’s body is carbon fiber. Composite finally becoming cool. I look forward to the rest of this series. That GRP allowed the small design studio (Two men, a dog, and a cigarette hanging in some cases reflecting the design studios’ image) to bring innovative designs to the automotive world. Design studios are used now by the big manufacturers. Those studios have respect today. The cottage industry of GRP car builders has been lost, because it was a cottage industry..difficult to see the patterns of development. Sixty years on, those patterns are being assembled as an important whole. The failure to recognize the contributions made by this cottage industry is a gap in fully understanding automotive development and history.