Hi Gang…

If you were going to build a chassis for your fiberglass bodied sports car back in the ‘50s – why not build one designed by Frank Kurtis? Frank made it easy for everyone interested. If you wanted to buy the real deal, you could get it directly from Kurtis Kraft with a serial number and knowing that you bought the best money could buy.

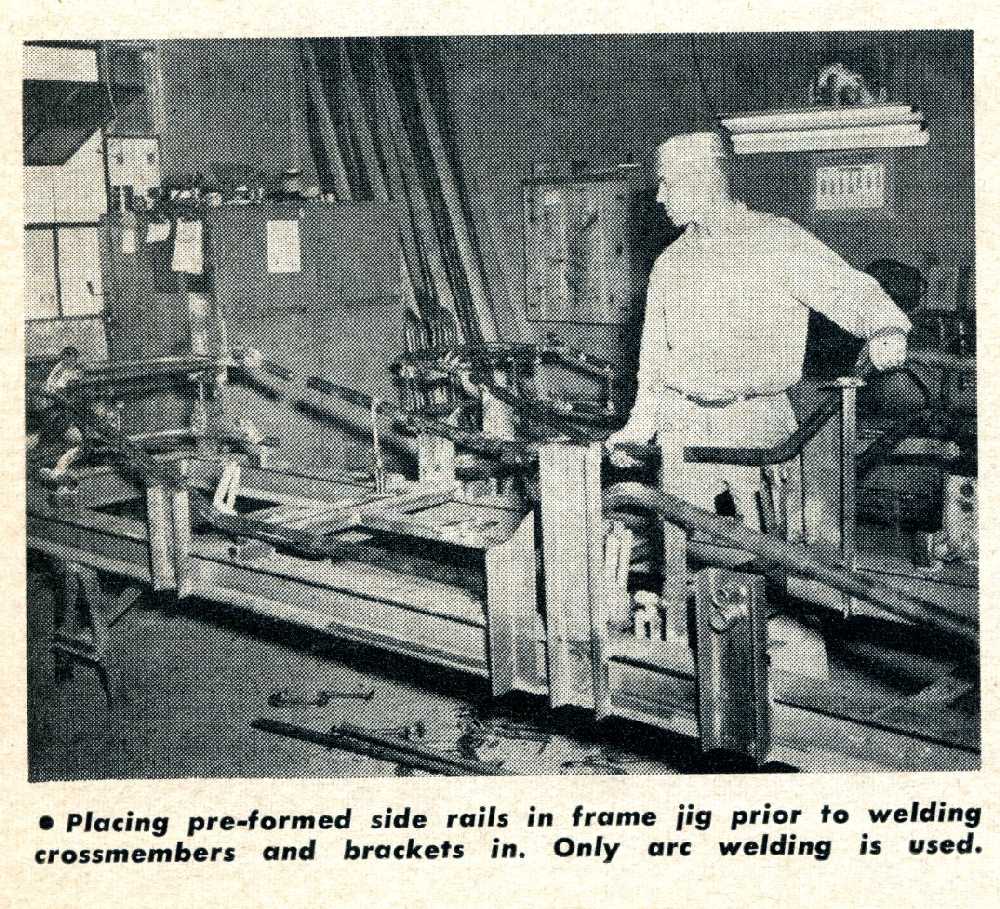

Or you could build it yourself. Frank Kurtis made plan sets available from his Glendale, California-based business but that wasn’t all – he published what you needed to do and how to build it in this article from Hot Rod Magazine in 1954. This is nearly a step-by-step article on how to build yourself a Kurtis 500 KK chassis for your sports car in the making.

Let’s see what Hot Rod Magazine had to say about how Kurtis built his frames and the rationale for the design and features he used to make the best one could buy.

Championship Chassis

Hot Rod Magazine, July 1954

By Bob Greene

Frank Kurtis is a big man and a busy man. To interview him on the fundamentals of his fabulous 500-KK tubular chassis must compare with the best efforts of those who try to pin a tail on one of Kurtis’s many Indianapolis contenders.

At the time of our visit Frank was supervising the last of eleven “Indy” cars to be entered in the big 500-mile torture test for 1954, his fifth year at the “Brickyard” (of 80 American cars entered in 1953, 41 were Kurtis built, 22 of the 33 starters flying his colors).

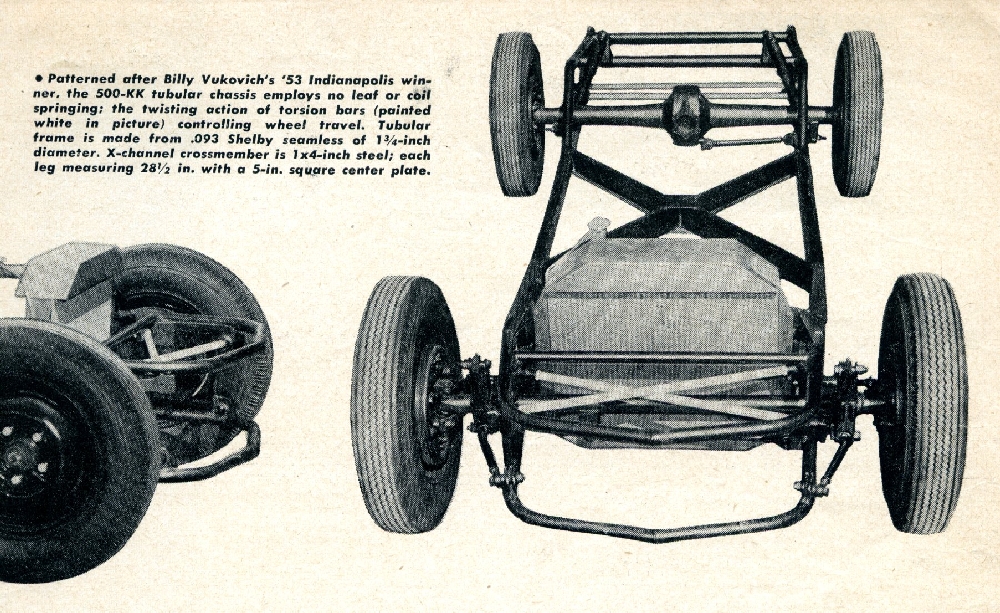

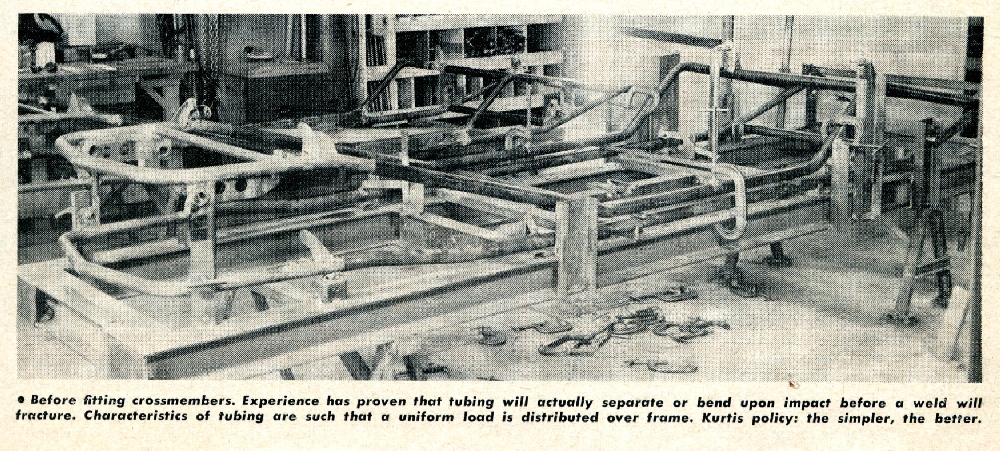

With the “Pukka” racing jobs stacked alongside the “bread and butter” 500-KK’s, it was immediately obvious that the two models were very similar in basic construction; the Indy jobs, of course, having a more elaborate side-sway control than the KK.

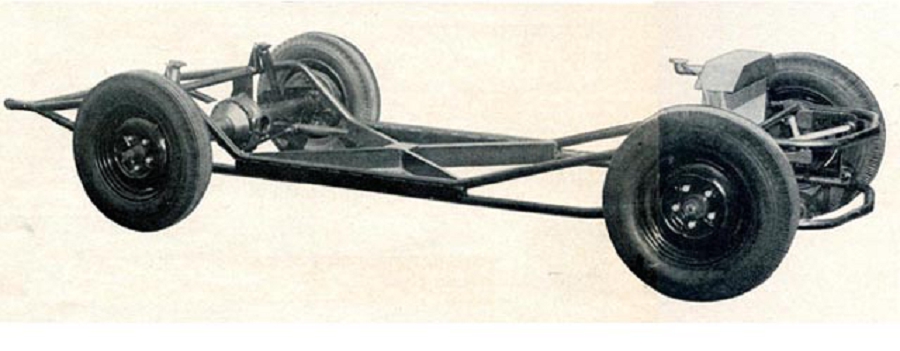

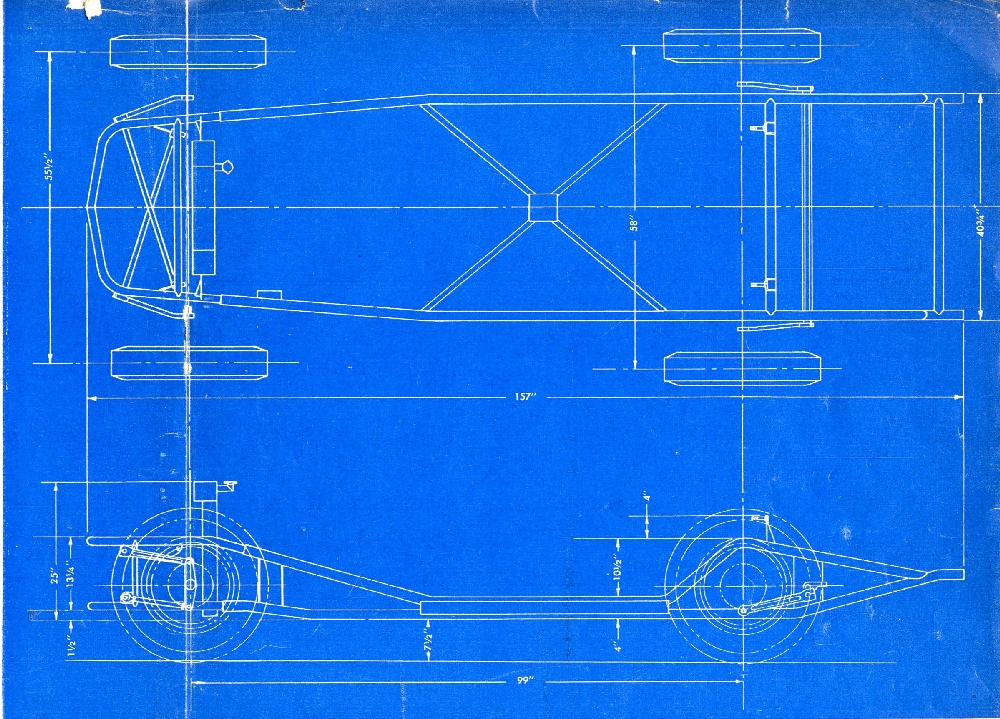

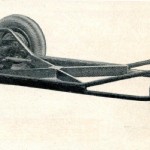

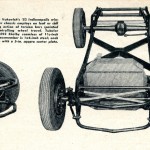

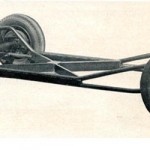

Herein lies the success of this 96-inch wheelbase champion chassis; the adaption of its track-proven but simple suspension system to a kit form Shelby tube chassis unit that can be purchased in part, or in total for $1290. With its low, clean-swept mid-ship section, the 740 pound chassis (with wheels and tires) is adaptable to almost any plastic or metal body or, for that matter, early roadster combination (outside frame width, 40 3/4 inches; frame length, 157 inches).

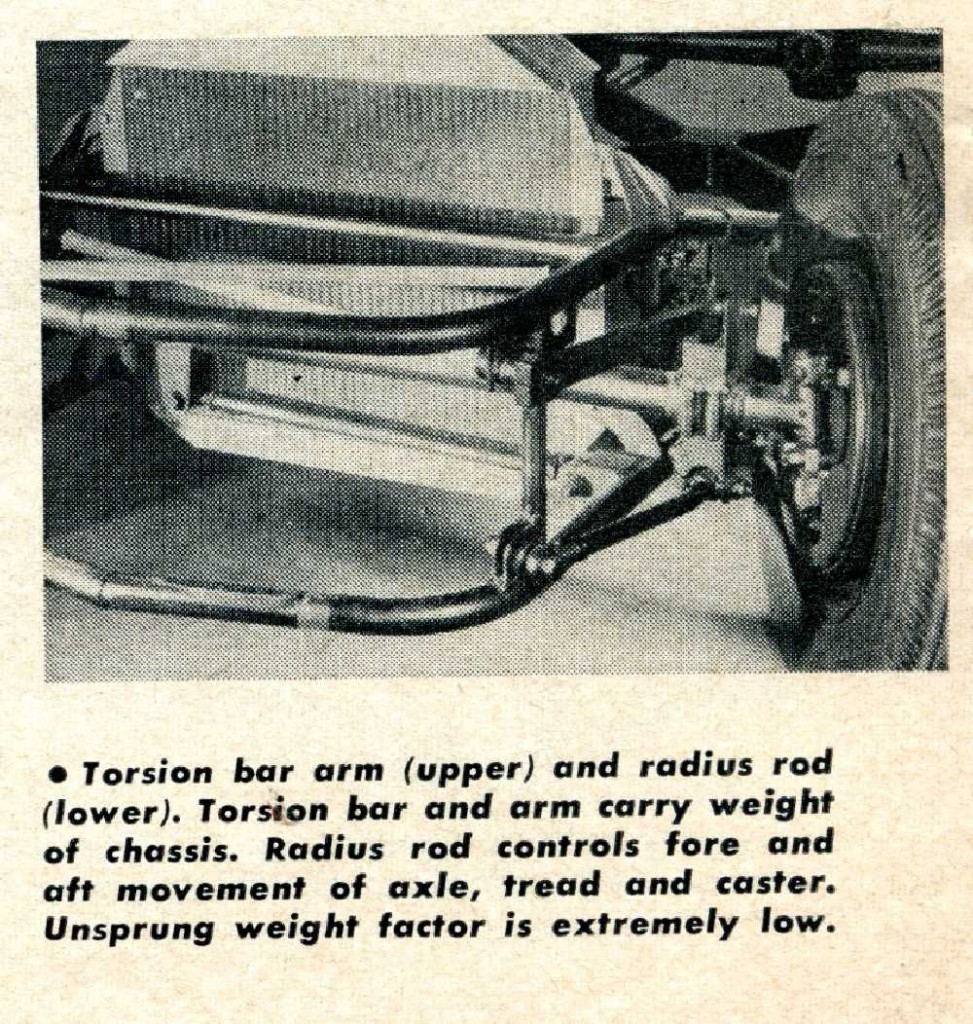

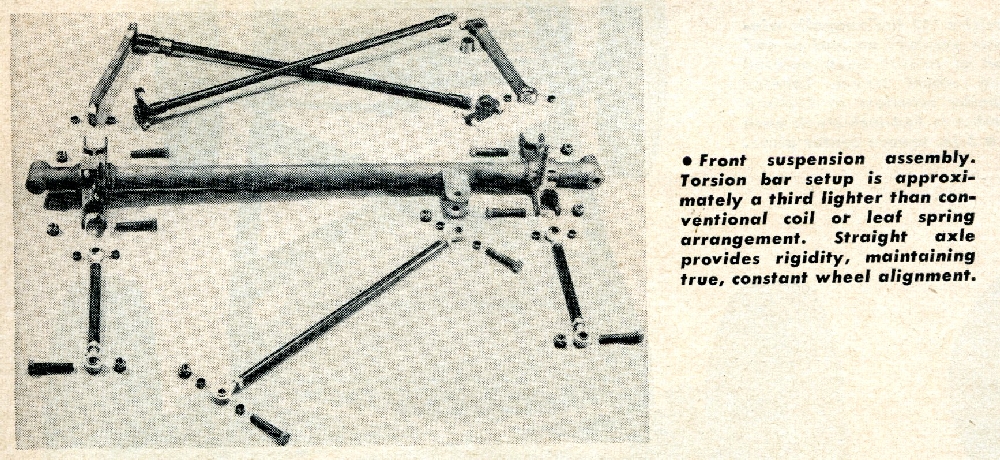

Aside from the lightness and lowness of the .093 seamless tube frame are the remarkable suspension features. The transverse torsion bar suspension system is 30% lighter than leaf or coil springing and unsprung weight is at a bare minimum.

You will notice that the front suspension arms are pivoted well ahead of the wheels while the rear arms are a like distance behind the wheels. Kurtis logic here: by moving the fulcrums as close out to the ends as possible a longer springbase is effected, thus a smoother ride combined with superior handling qualities of a shorter wheelbase model.

Another noteworthy feature of the torsion bar system is the lateral stability that can be gained by the extreme sideward positioning of the swinging arms. With the spring fulcrum outside the frame rather than inside it, considerably flatter and faster cornering can be done. The wheels, hung on a straight, 4130 seamless steel tube front axle, swing in a very slight arc, allowing little change in steering geometry when turning. By the same token, the face of the tire against the road surface remains much more constant under the same circumstances, thus retarding scuff and the moment of a slide.

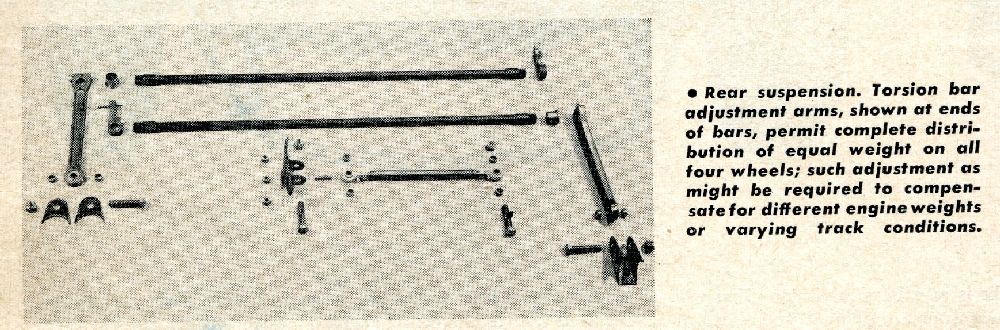

So far we’ve noted that all four wheel pivots have been moved as far out towards the corners as possible in the best interests of stability. An additional benefit of hanging the rear wheels in this manner is one of traction upon acceleration. As power is applied, the weight is advantageously shifted to the rear where it settles hard, giving the least amount of wheel hop and skid.

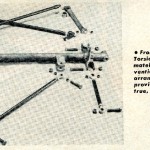

A simplified adjustment of the torsion bar system permits the raising or lowering of any one or combination of corners of the frame according to varying conditions of track or road surface. Each bar, mounted on Oilite bearings, has an adjustment arm and set screw arrangement on its anchored end to permit turning of the bar approximately 15 degrees of arc which raises or lowers the corresponding wheel accordingly.

Panhard (anti-sway) bars front and rear locate the suspension to the frame and control sidesway. Made from 7/8-inch chrome moly tubing, the rear bar is 14 inches long and the front, 21 inches. Both have aircraft self-aligning rod ends.

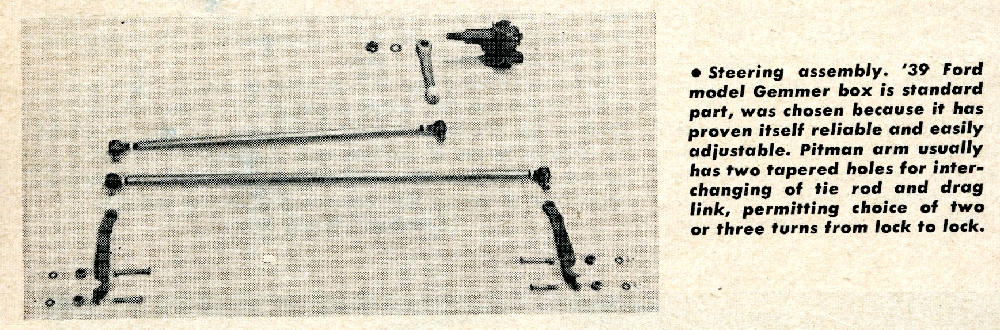

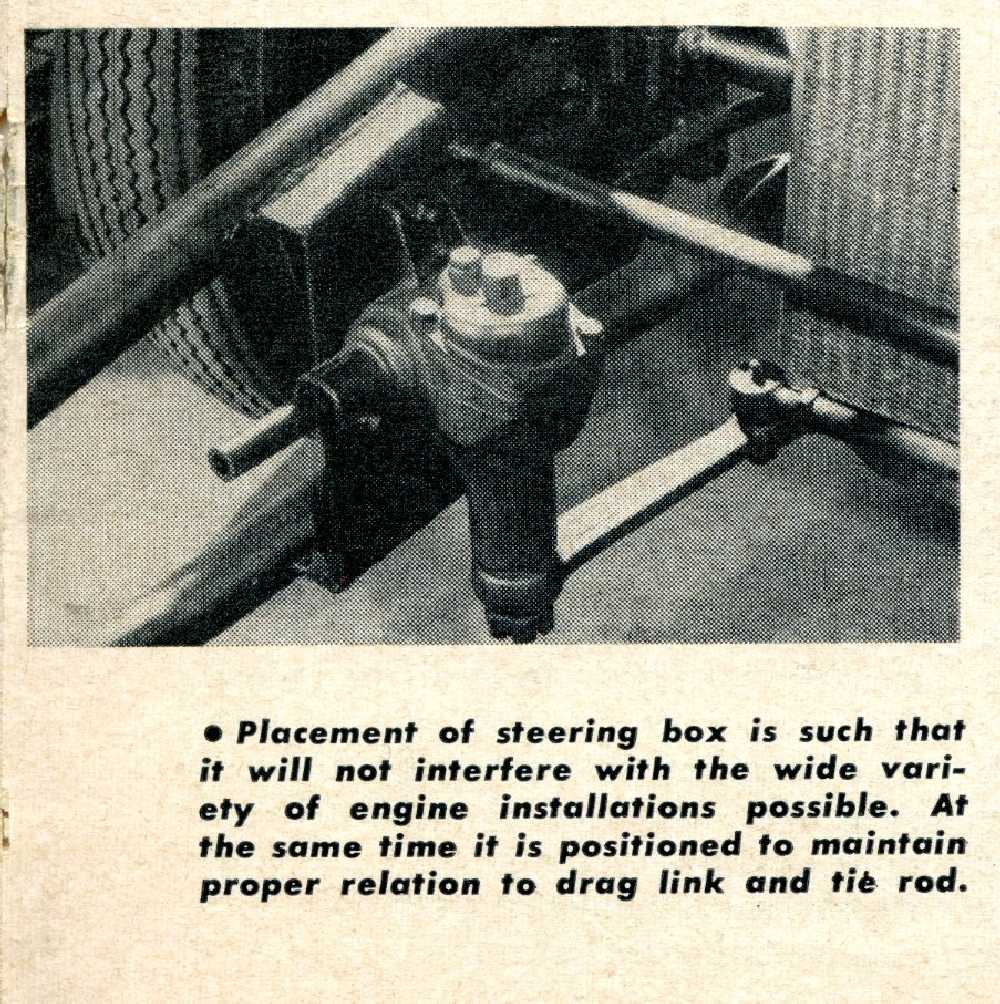

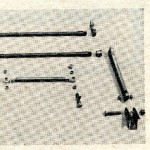

There’s novelty again in the steering arrangement; a choice between two or three turns from lock to lock. The selection is made possible by using a special Pitman arm and drag link setup. Merely by transposing the tie rod and drag link connections in the two Pitman arm end holes, the ratio can be changed on very short notice.

And, to top it all off, the running gear (including spindles, hubs, drums, brakes and wheels) is made up of standard Ford parts. The steering gear (Gemmer) and rear axle housing are also Ford, making for easy and economical replacement. The whole package is efficient and practical from every angle. Built in the direct light of racing experience, it is difficult to imagine a more ideal touring or road racing chassis, one capable of handling up to 450 horsepower.

Summary:

Many enterprising young men did just what they read – they used this article and others about the Kurtis chassis to build their own version of a frame for their sports car. You could build a frame designed by Chuck Manning, the Kurtis 500 KK chassis discussed here, or a creation of your own if you had the time, money, and skill to do the job.

And you can today too. If you are building a frame for your vintage fiberglass sports car, why not “Kurtis?” He made it easy to do and even provided the plans shown here today. Between choices from Chuck Manning and Frank Kurtis, you couldn’t go wrong back then – and today you’d be right on the money.

Hope you enjoyed the story, and until next time…

Glass on gang…

Geoff

——————————————————————-

Click on the Images Below to View Larger Pictures

——————————————————————-

Hi,where can I find the building plans of kurtis chassis 500KK

The gyroscopically induced phenomenon of “wheel tramp”, an alternating lifting of each front wheel off the pavement is the dreaded affliction of beam front axles. It comes I would guess from forcing a steering input while experiencing an excitation bump simultaneously. It was never really curable. Anyway, I am goin’

stuck on that idea of an excitation “bump.”

Pretty darn fine any way you slice it… simple and to the point. Mind you straight front axle cars are not noted for their superlative handling attributes but it was certainly a means to an end. Would actually be kind of fun to do a modern rendition of that chassis.