Hi Gang…

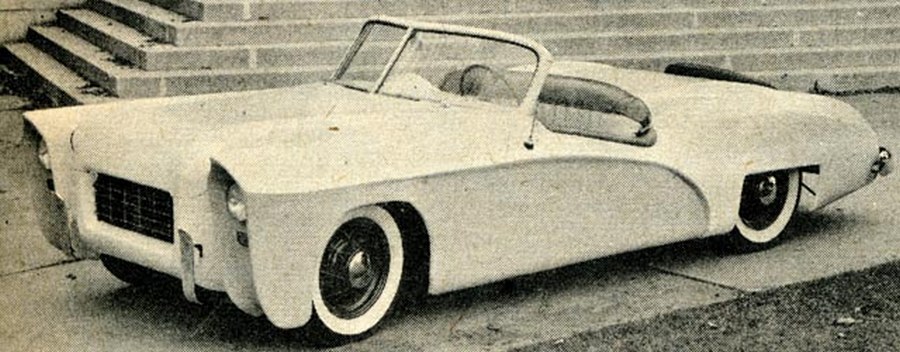

Few stories from the 50s document in such detail the trials and tribulations of designing and building your own fiberglass sports car. This story captures the work completed by Bob Winberg and Pete Anderson of Floral Park, New York and their car called the “Winson” which took them approximately three years to finish.

This is a two-part story that appeared in two separate issues of the magazine “Speed Mechanics” in 1955. The story here today is approximately 2600 words and the one that will follow is nearly the same word count. Very impressive that a magazine would dedicate such a detailed story to their readership – a testimony to how interested the public was in building such a car and learning how to do it – ringside – as you’ll see in this first of a two-part story that appears today here on “Forgotten Fiberglass.”

So without delay, let’s meet our brave heros – Bob Winberg and Pete Anderson. Away we go….

Building a Glass Rod

Speed Mechanics: April-May 1955

By Fred Horsley

Photos by Ozzie Lyons, Bob Hess, and Pete Anderson

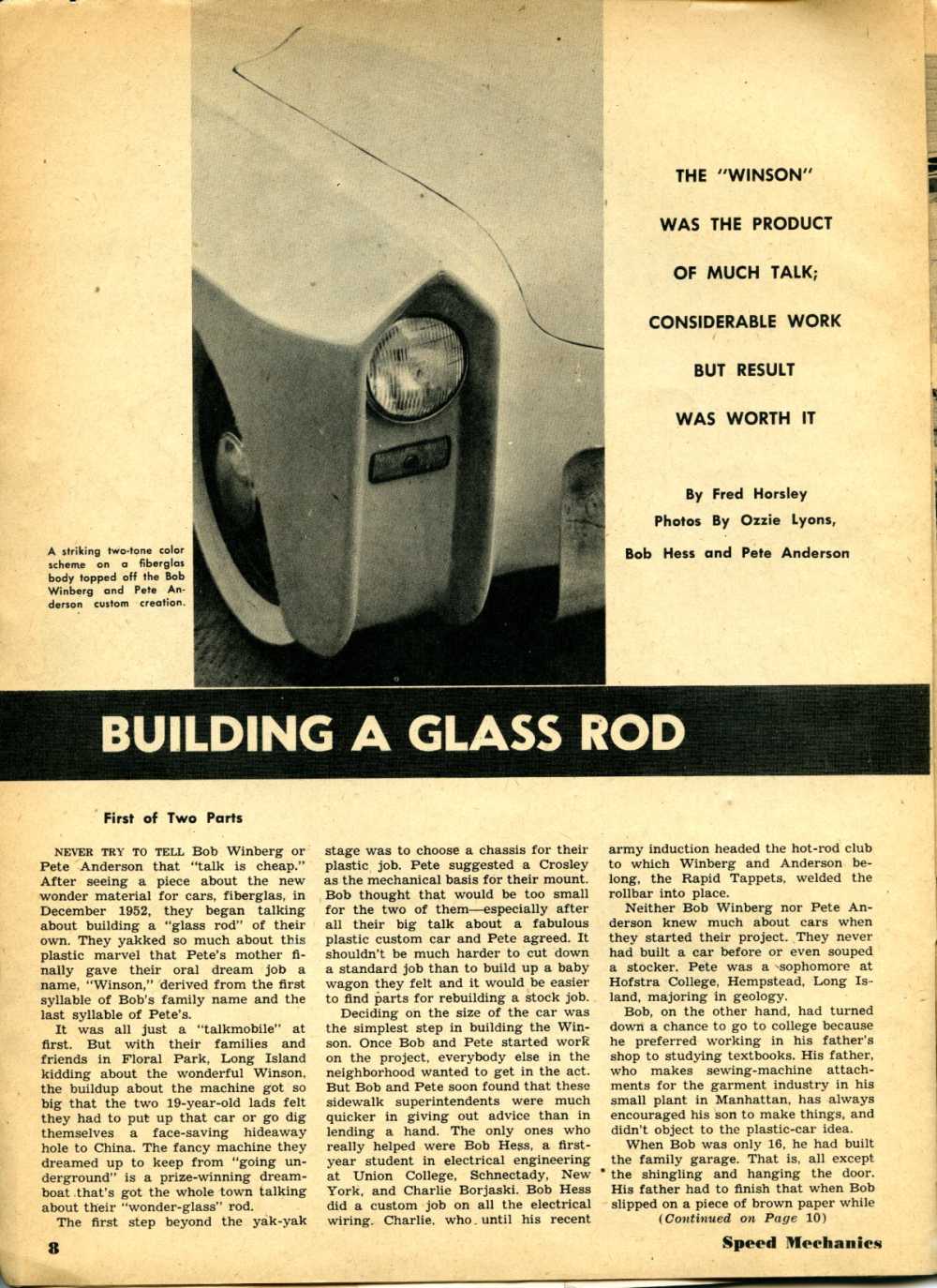

The “Winson” was the product of much talk; considerable work, but result was worth it…

Never try to tell Bob Winberg or Pete Anderson that “talk is cheap.” After seeing a piece about the new wonder material for cars, fiberglass, in December 1952, they began talking about building a “glass rod” of their own. They yakked so much about this plastic marvel that Pete’s mother finally gave their oral dream job a name, “Winson,” derived from the first syllable of Bob’s family name and the last syllable of Pete’s.

It was all just a “talkmobile” at first. But with their families and friends in Floral Park, Long Island kidding about the wonderful Winson, the buildup about the machine got so big that the two 19 year old lads felt they had to put up that car or go dig themselves a face-saving hideaway hole to China.

The fancy machine they dreamed up to keep from “going underground” is a prize-winning dreamboat that’s got the whole town talking about their “wonder-glass” rod. The first step beyond the yak-yak stage was to choose a chassis for their plastic job. Pete suggested a Crosley as the mechanical basis for their mount. Bob thought that would be too small for the two of them – especially after all their big talk about a fabulous plastic custom car and Pete agreed.

It shouldn’t be much harder to cut down a standard job than to build up a baby wagon they felt and it would be easier to find parts for rebuilding a stock job. Deciding on the size of the car was the simplest step in building the Winson. Once Bob and Pete started working on the project, everybody else in the neighborhood wanted to get in the act.

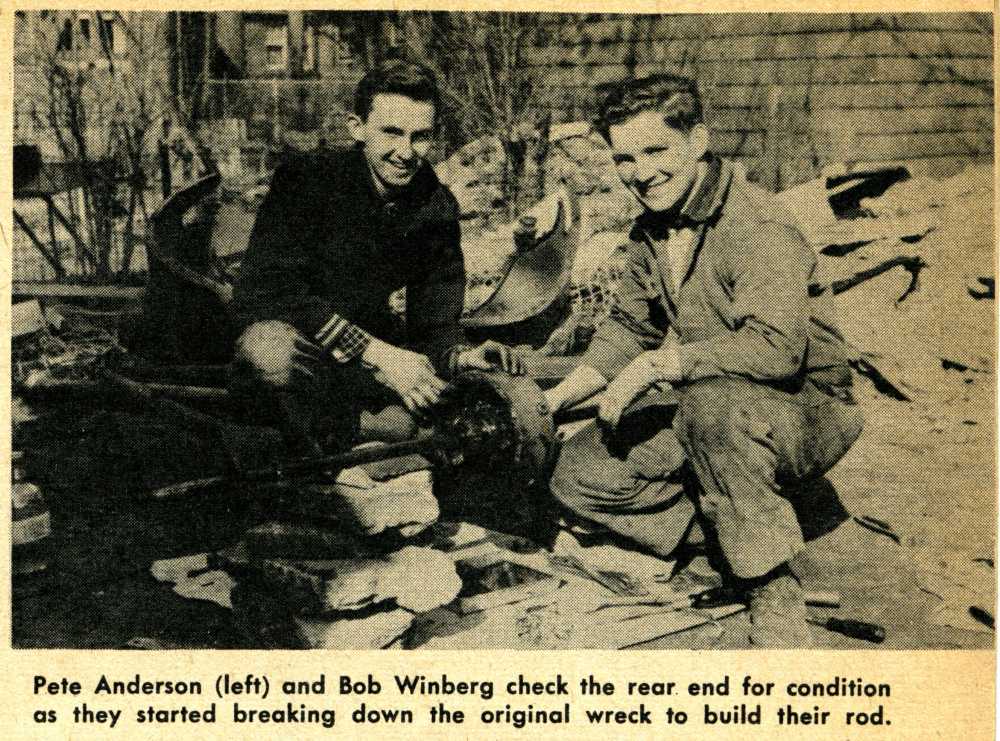

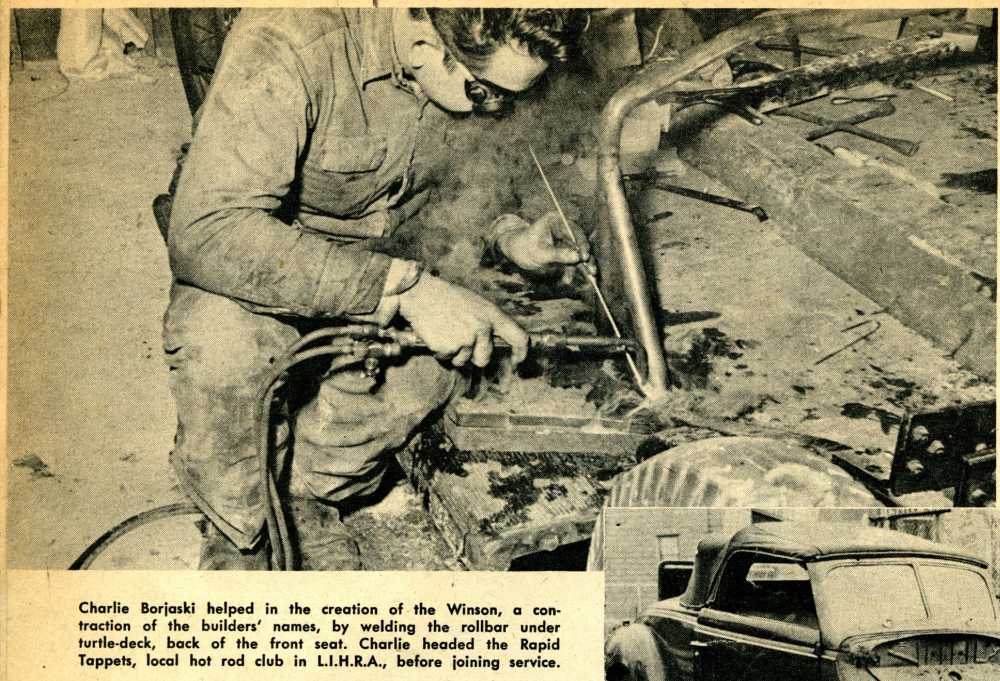

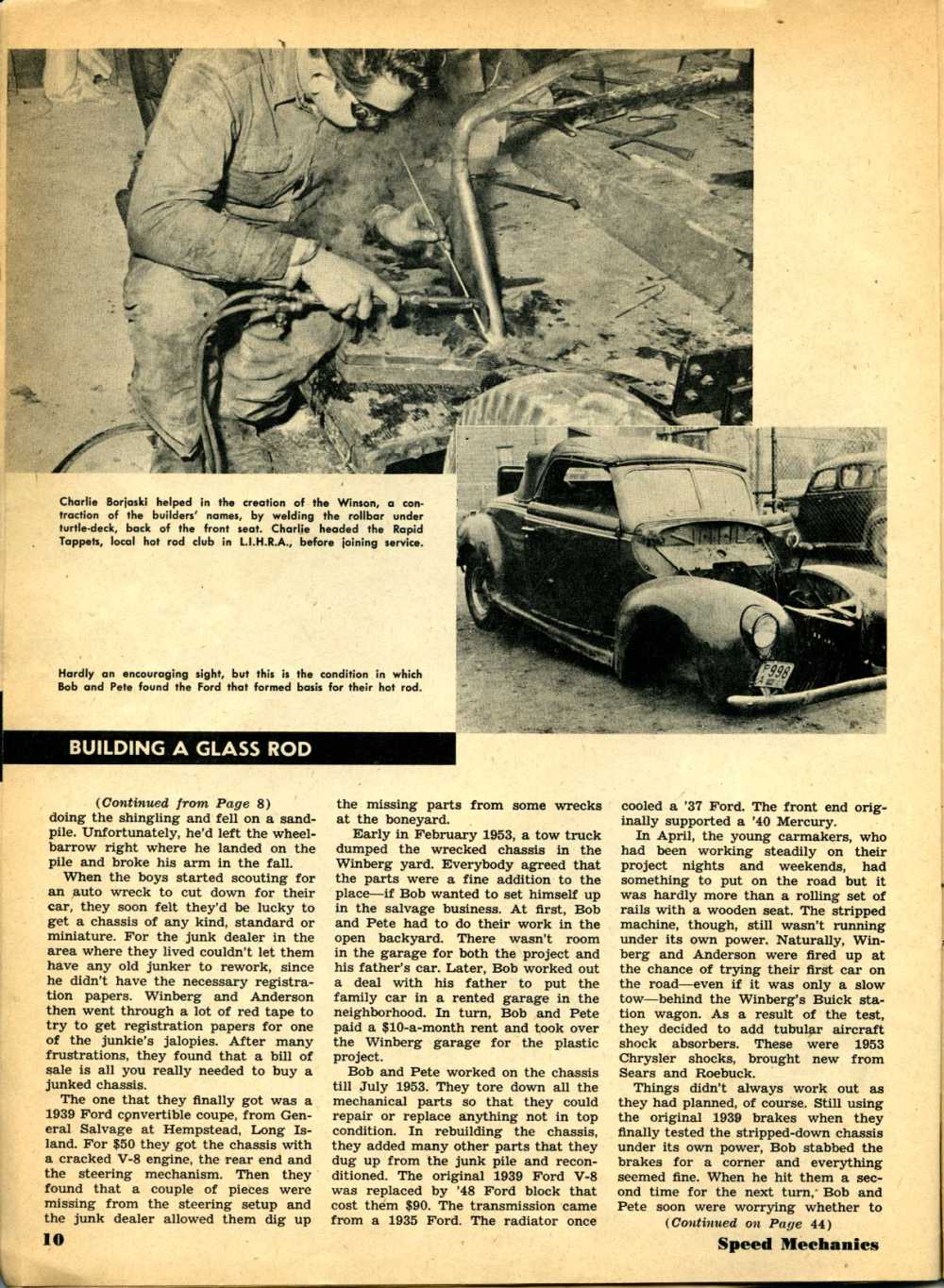

But Bob and Pete soon found that these sidewalk superintendents were much quicker in giving out advice than in lending a hand. The only ones who really heled were Bob Hess, a first-year student in electrical engineering at Union College, Schnectady, new York, and Charlie Borjaski.

Bob Hess did a custom job on all the electrical working. Charlie, who until his recent army induction headed the hot-rod club to which Winberg and Anderson belong, the Rapid Tappets, welded the rollbar into place. Neither Bob Winberg nor Pete Anderson knew much about cars when they started their project. They never had built a car before or even souped a stocker. Pete was a sophomore at Hofstra College, Hempstead, Long Island, majoring in geology.

Bob, on the other hand, had turned down a chance to go to college because he preferred working in his father’s shop to studying textbooks. His father, who makes sewing-machine attachments for the garment industry in his small plant in Manhattan, has always encouraged his son to make things, and didn’t object to the plastic-car idea.

When Bob was only 16, he had built the family garage. That is, all except the shingling and hanging the door. His father had to finish that when Bob slipped on a piece of brown paper while doing the shingling and fell on a sandpile. Unfortunately, he’d left the wheel barrow right where he landed on the pile and broke his arm in the fall.

When the boys started scouting for an auto wreck to cut down for their car, they soon felt they’d be lucky to get a chassis of any kind, standard or miniature. For the junk dealer in the area where they lived couldn’t let them have any old junker to rework, since he didn’t have the necessary registration papers.

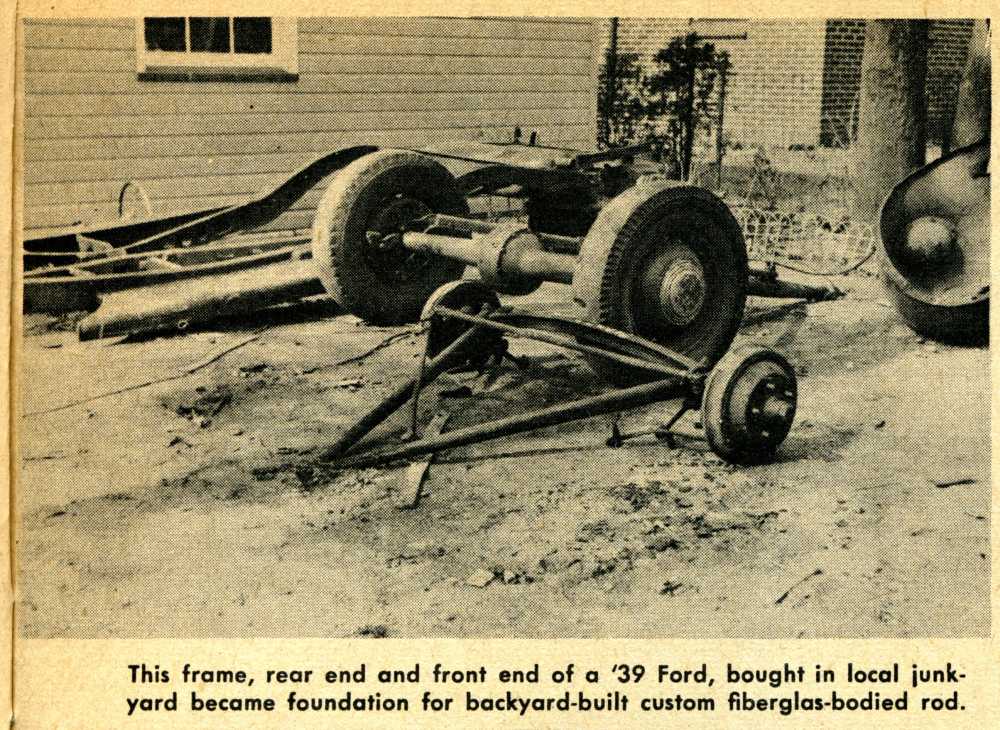

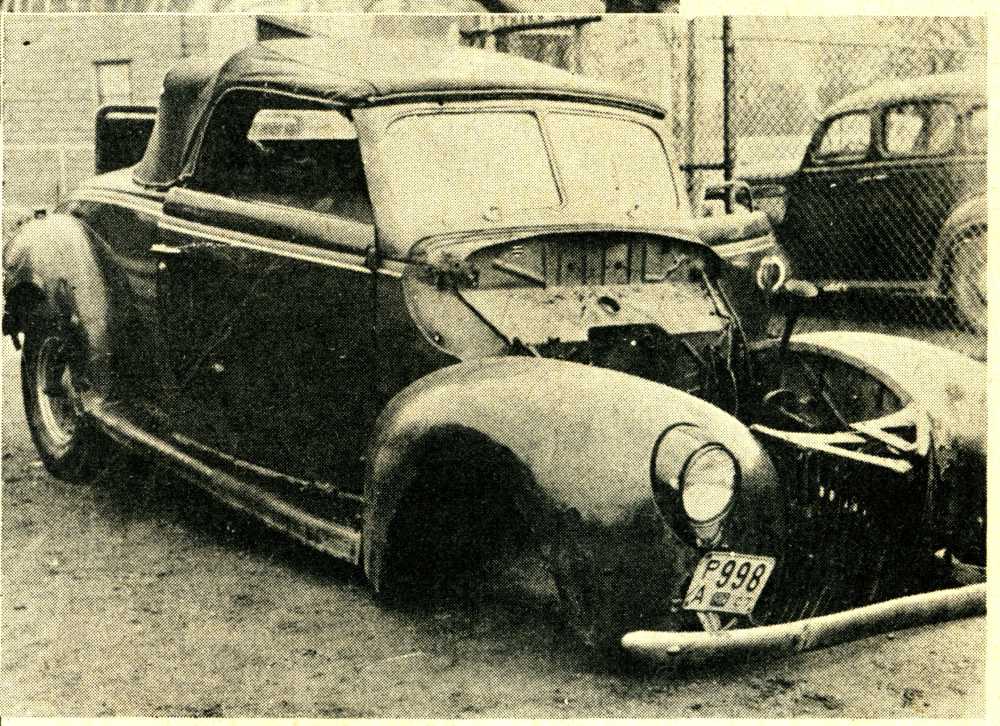

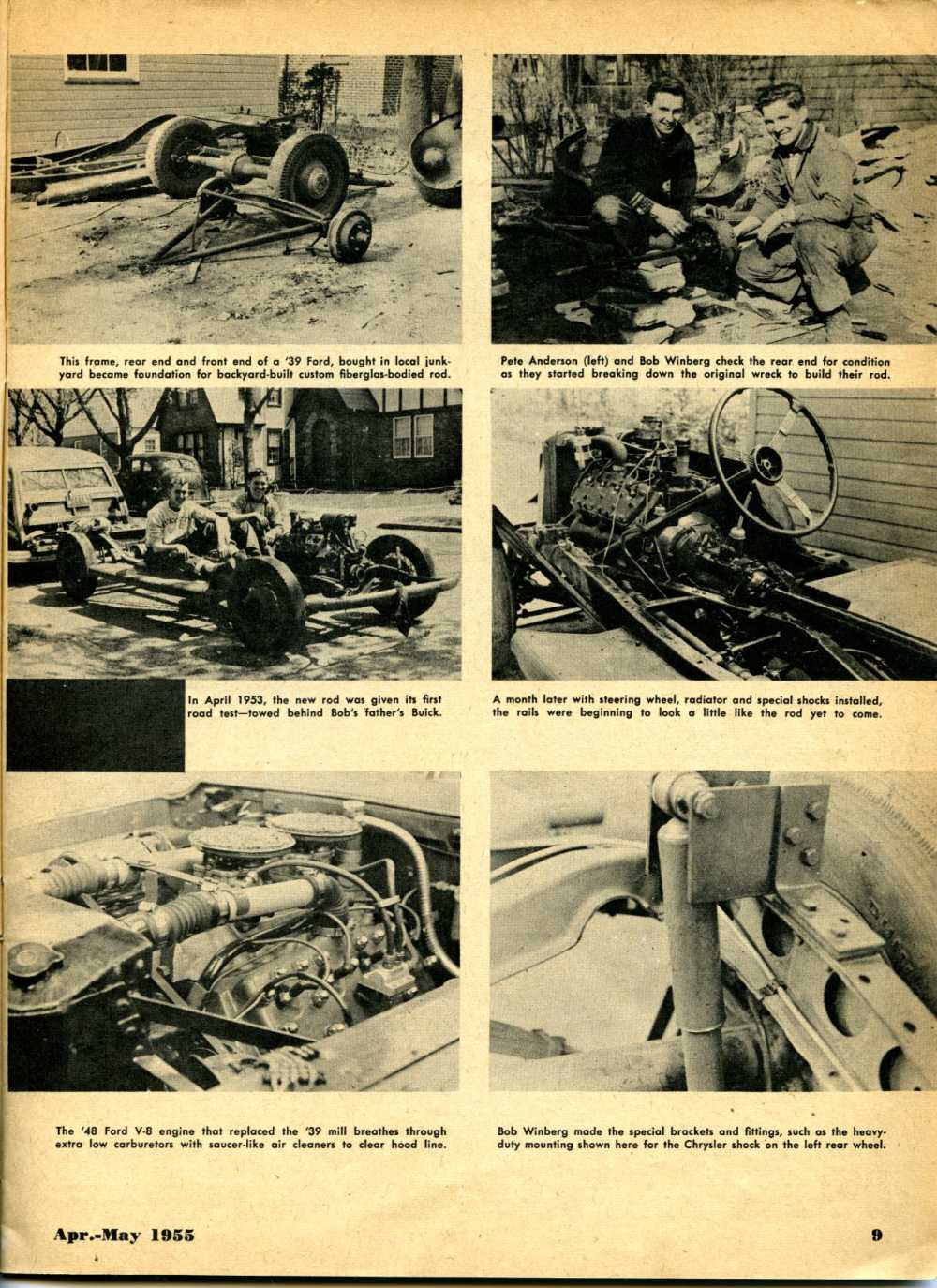

Winberg and Anderson then went through a lot of red tape to try to get registration papers for one of the junkie’s jalopies. After many frustrations, they found that a bill of sale is all you really needed to buy a junked chassis. The one that they finally got was a 1939 Ford convertible coupe, from General Salvage at Hempstead, Long Island.

For $50 they got the chassis with a cracked V-8 engine, the rear end and the steering mechanism. Then they found that a couple of pieces were missing from the steering setup and the junk dealer allowed them to dig up the missing parts from some wrecks at the boneyard.

Early in February 1953, a tow truck dumped the wrecked chassis in the Winberg yard. Everybody agreed that the parts were a fine addition to the place – if Bob wanted to set himself up in the salvage business. At first, Bob and Pete had to do their work in the open backyard. There wasn’t room in the garage for both the project and his father’s car.

Later, Bob worked out a deal with his father to put the family car in a rented garage in the neighborhood. In turn, Bob and Pete paid a $10 a month rent and took over the Winberg garage for the plastic project. Bob and Pete worked on the chassis ‘till July, 1953. They tore down all the mechanical parts so that they could repair or replace anything not in top condition.

In rebuilding the chassis, they added many other parts that they dug up from the junk pile and reconditioned. The original 1939 Ford V-8 was replaced by a ’48 Ford block that cost them $90. The transmission came from a 1935 Ford. The radiator once cooled a ’37 Ford. The front end originally supported a ’40 Mercury.

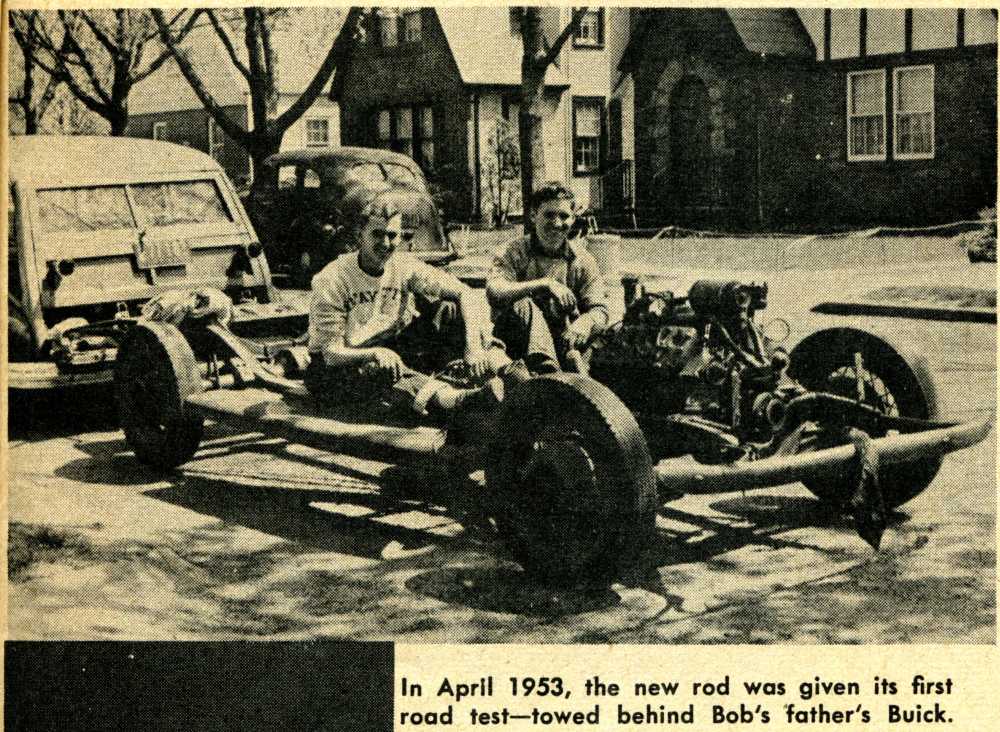

In April, the young carmakers, who had been working steadily on their project nights and weekends, had something to put on the road but iit was hardly more than a rolling set of rails with a wooden seat. The stripped machine, though, still wasn’t running under its own power. Naturally, Winberg and Anderson were fired up at the chance of trying their first car on the road – even if it was only a slow tow – behind the Winberg’s Buick station wagon.

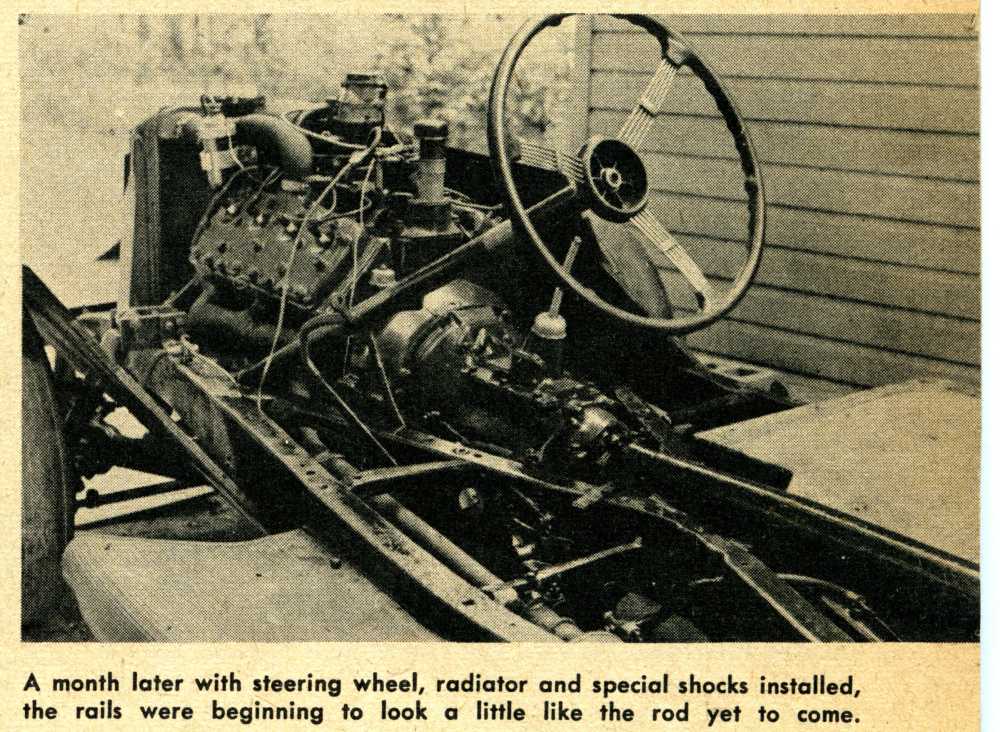

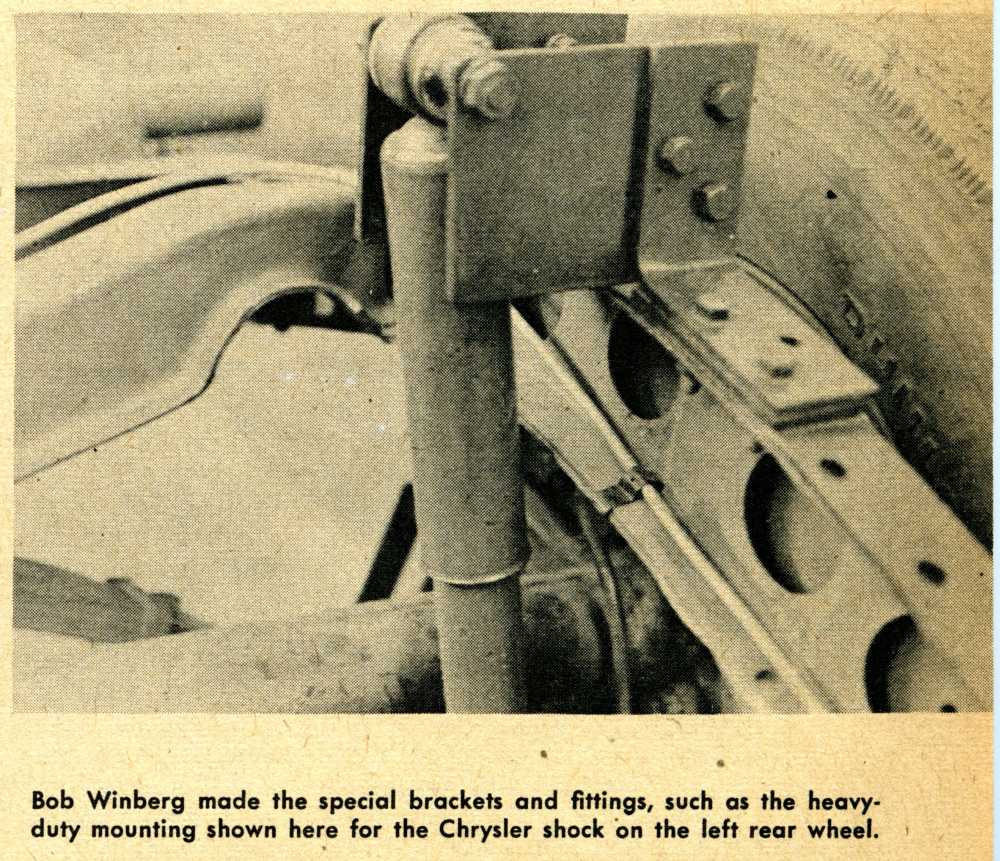

As a result of the test, they decided to add tubular aircraft shock absorbers. These were 1953 Chrysler shocks, brought new from Sears and Roebuck. Things didn’t always work out as they had planned, of course. Still using the original 1939 brakes when they finally tested the stripped-down chassis under its own power, Bob stabbed the brakes for a corner and everything seemed fine.

When he hit them a second time for the next turn, Bob and Pete soon were worrying whether to jump or try dragging their feet to slow down their suddenly brakeless contraption. The brake line had blown at a corroded spot. Fortunately, Bob was rolling the machine very slowly and when he eased up on the accelerator engine compression slowed the machine enough to make the turn and gradually come to a halt.

That was the end of the road for the original brake lines. They bought new stock hydraulic lines from a Ford dealer. The wheels were replaced by stock ’35 Fords and the drums were turned down by Hempstead Machine. All four wheels mount 6.00 by 16 inch tires.

The original ’39 radiator was replaced because of a washer. In reassembling the fan, Bob forgot to put back one washer. When he started up the engine for a test run, he though the machine suddenly had decided to try a vertical takeoff. As the engine revved up, the speeding fan flew against the radiator and started eating its way through the honeycomb. So, for lack of a left-off washer, the boys made another journey to the junkyard and returned with a ’37 core.

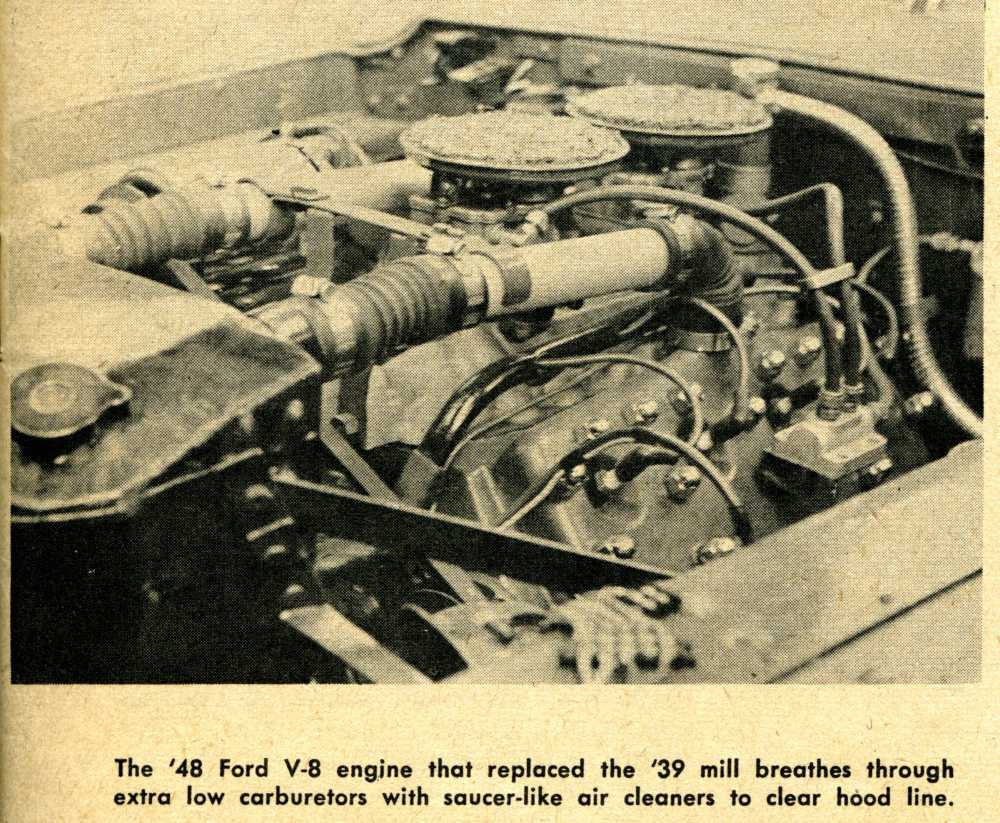

The ’48 Ford V-8 that substituted for the original ’39 Ford engine with the cracked block was stock when it was first installed in the rebuilt chassis. Because of the low hood line that they wanted, Pete and Bob had to modify the carburetion. While they were redoing the carburetion, they made a few other changes, too.

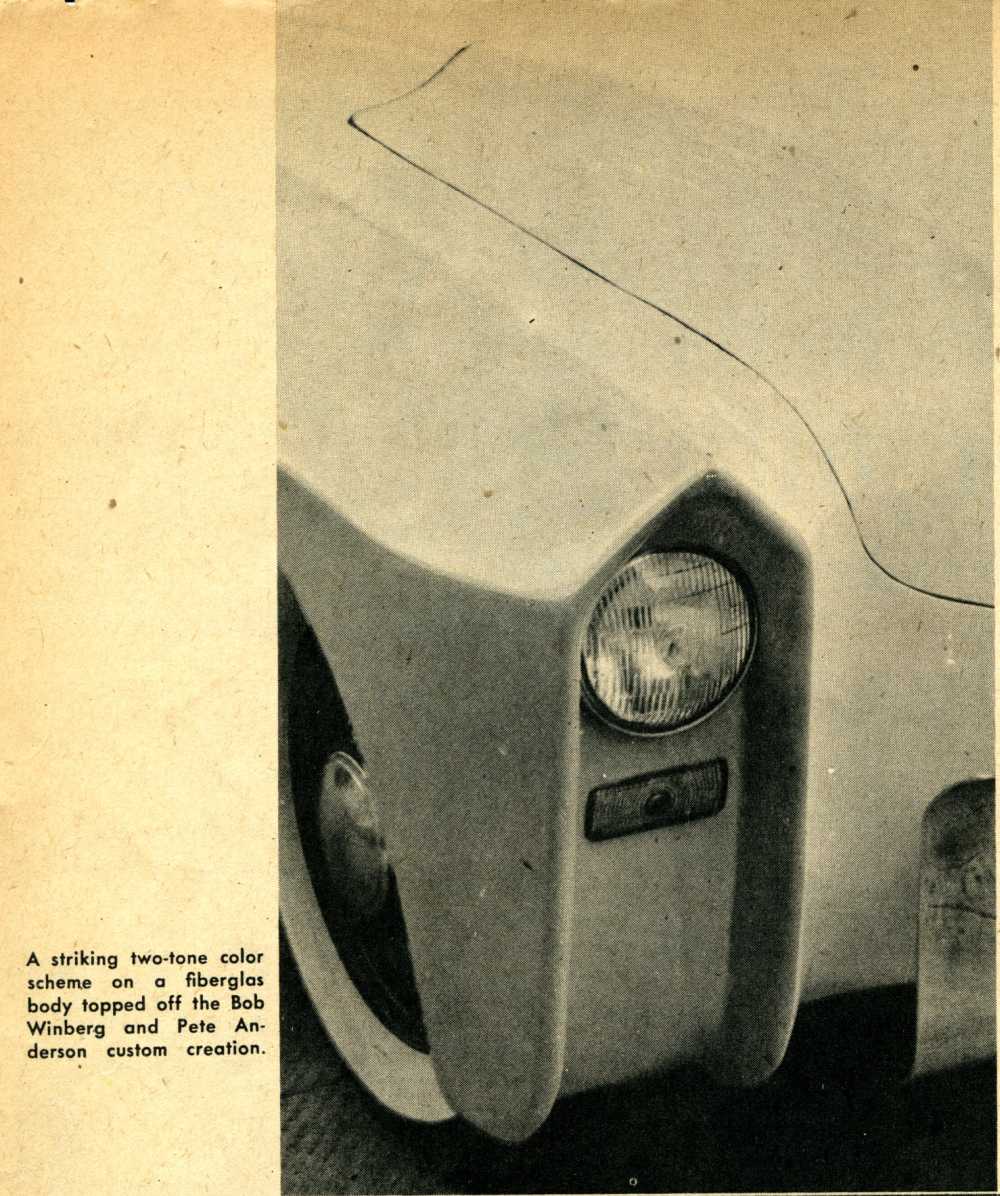

Since the big job was to be the plastic body, they decided to give the engine only a moderate hopup. The main problem was to find the manifold and carburetors that could fit under a low hood. After looking at several lines of speed equipment, Winberg and Anderson purchased a dual manifold because it was the lowest built one that they could find.

For the dual carburetors the boys got two Stromberg 97’s. Bob cut off a half inch from the top so that the carburetors would fit under the hood. Though the jugs were stock at the start, they were completely renovated. Ohman brothers in Hempstead re-worked the pots using .035 main jets.

The boys took out the bull check valve on the accelerator plunger and put a bypass hole in the dump jet. The air cleaners were cut-down so that the “saucers” are only a half inch high. The two fellows did the work with a hacksaw and file. The chokes also had to be cut in half to clear the chopped-down air cleaners.

Other modifications to the engine included Malory coils for dual ignition and a boost in the compression ratio a point above stock bringing the ratio to 7.7 to 1. Instead of using high-compression cylinder heads our car-makers had the stock heads milled .050 inch. Since this requires special precision work for good results, they had the same shop that did the brake work, Hempstead Machine, do the milling.

From two junked ’35 Fords, the boys got the exhaust pipes to make dual exhaust pipes for their car and the Winson chassis got new stock Ford mufflers to go with the homemade duals. As a safety protection against fire, the boys used one-half inch plywood faced with 20 gauge sheet iron for the firewall and side panels to the engine compartment. The sheet iron, of course, is on the side toward the engine, and the plywood merely serves as a stiffener.

The V-type windshield was what Bob called “a big experiment.” The windscreen frame came from a wrecked ’49 two-door Hudson Hornet. First of all, it was wider than necessary for the body design. The cowling later had to be built up more than the scale model they had made indicated. The big trouble, though, was the open-frame channel. The channel iron was 1 and ½ inches wide, and had an 1/8th inch wall and a ¾ inch channel.

Bob tried to fill the hollow with copper tubing and leading. In July, on the hottest day of the summer, Bob poured 30 pounds of lead along the top of the open-angle frame. Some of the molten lead splattered, burned a small scar on his upper arm and also ruined the 1951 Ford circular instrument dial by searing a small hole through its face. It was a long, sizzling day then before Winberg finished leading out the windshield frame.

For all that hot work, the ruined instrument unit and the souvenir burn on Bob’s arm, the boys found that they had a smooth, solid-looking windshield frame. But when they tried out the chassis with the re-worked windshield, the frame proved anything but solid. That extra 30 pounds of lead made it shimmy as if it would vibrate off the vehicle on a turn.

The windshield had to be as solid as it looked, since everyone who wanted a closer look always leaned on it. The boys used three 1 and ½ inch channel-iron sections on each side of the windshield frame to brace it. Anothre brace fastened the center frame member to the firewall. Besides the channel-iron bracers, three turnbuckles, running forward from the side and center of the frames’ three “legs,” kept the frame pulled tightly to give it additional strength when anyone leaned on it.

Despite all the special bracing, the windshield still vibrated enough to make you wonder if the glass might pop out. So, the “big experiment” called for more research. Eventually Bob had to admit that the 30 pounds of leading along the top of the frame was a mistake. He spent another half-day with the torch to burn out all the leading that he had so painfully and laboriously worked into the frame to give it a solid look.

In its place he used a fiberglass putty. With a silica compound powder he made a paste so thick that it didn’t flow. The he let this so-called putty harden on the frame for about a week. To smooth it off in a round, even finish he found that he could work it down as he had done the lead, with a file.

It seemed odd to him that there was no metallic clink as he shaved down the hardened material by rasping the file back and forth. The finished putty seemed to form a solid piece with the channel iron so that with a little paint on the surface you would think that the frame was solid.

The lightening of the top-heavy windscreen with the fiberglass putty did stop the violent vibration, but still left a slight trace of shimmy in the windshield when the car cornered. It took four weeks of spare time or about 16 hours of weekends and nights for the boys to make the floorboards. These they made up with 3/8 inch plywood brushed very thick with creosote to protect the wood from dampness and warping.

All the woodwork in the car got a heavy brushing with creosote, then with linseed oil as both preservative and guard against moisture. The running boards on the original ’39 Ford were still sturdy and had no rust spots. Bob and Pete, therefore, decided to use the running boards as well as the edges of the floorboard as a platform to help support the body shell.

To brace the running board they used seven aluminum outriggers 5/8 inch by 1 and ½ inches on each side of the car. Bob, who had been making all the brackets, metal fittings and other custom parts in his father’s shop after hours, made up these braces as well as the other special metalwork used in the car.

With the basic chassis completed in July 1953, the boys found they couldn’t shy away from the big problem, that fiberglass body, any longer. They knew they wanted a low, rakish, streamlined shell but couldn’t find the practical details on how to work out that structure in any of the automotive publications.

Bob and Pete had sent away for a dollar pamphlet advertised in an automotive magazine. The pamphlet, though, Bob found, made the “lowdown” on building a plastic car sound much easier and simper than the job turned out when you had to figure out just what to do at each stage and where to get supplies and basic equipment.

Bob spent a full day in research at the huge New York Public Library on 42nd Street to come up with some helpful advice on how to proceed in building a plastic-car body. That day was wasted. The library had nothing available on the subject. How finally obtained the necessary information on working with fiberglass and what their finished glass rod looks like will be revealed in the next issue of “Speed Mechanics.” If you have a similar project in mind, the story of how they completed their car and the mistakes they made will help you to produce a model of which anyone could be proud.

Summary:

What an fascinating step-by-step review that documents the challenges young men such as Bob and Pete had in achieving their dream – designing and building their own fiberglass bodied sports car. In part two of this article, we’ll see the final design come together and the uphill climb it was to do just that. Stay tuned here on Forgotten Fiberglass…

Hope you enjoyed the story, and until next time…

Glass on gang…

Geoff

Thanks for having this article Bob Winberg was my brother, I recall all the work he and Pete did, making this. We had fiberglass in everything for years. I wanted to share his story with a friend – and here it is.

the second part and pictures of the WINSON story seems to be missing on your website??? What am I missing?

@Bob Hess….let’s talk this week and get part 2 rolling. Can you give me a call at 813-888-8882. Thanks Bob.

Great story love the photos…

Mel Keys