Hi Gang…

I was quite surprised to find this article. It was sent in by good friend Richard “Dick” Lewis who built and still owns his original Allied Swallow Coupe – more about that in a future article here at Forgotten Fiberglass.

What Dick had shared with me was a fascinating article for at least two reasons:

* It was the earliest article that we’ve found that focuses on a comprehensive history of Bill Devin and his sports cars

* It does a very good job at discussing the history of building your own sports car in America in the 1950s and beyond.

The only issue I’m still struggling with a bit is that the article is a bit negative or down on the idea that people could and did do a remarkable job at completing this daunting task. As I read it, it talked more about what didn’t get done than what did. And I didn’t agree with how the characterized the early cars from the 1950s – that I have no qualms about saying.

Given these cautionary notes, I still think the article is important and nicely done. And it gives a clear and unequivocal point of view from someone in 1980 looking backward on a very significant car – the Devin – the man who built it and the industry from which it was birthed.

So….off we go and I hope you enjoy the article:

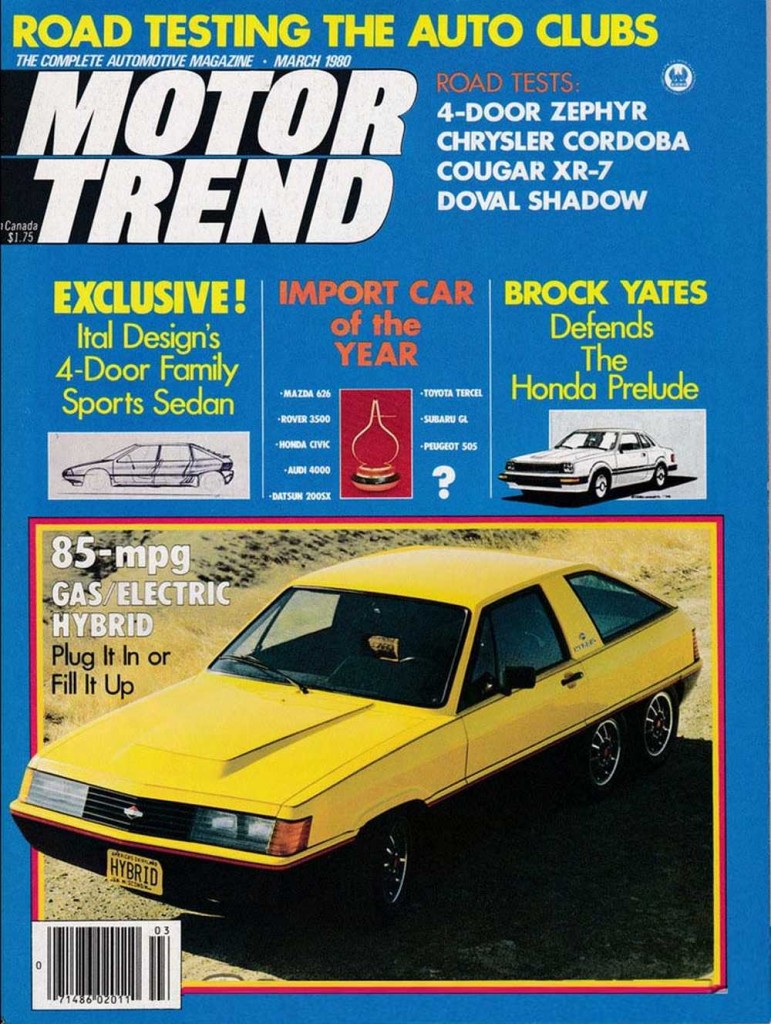

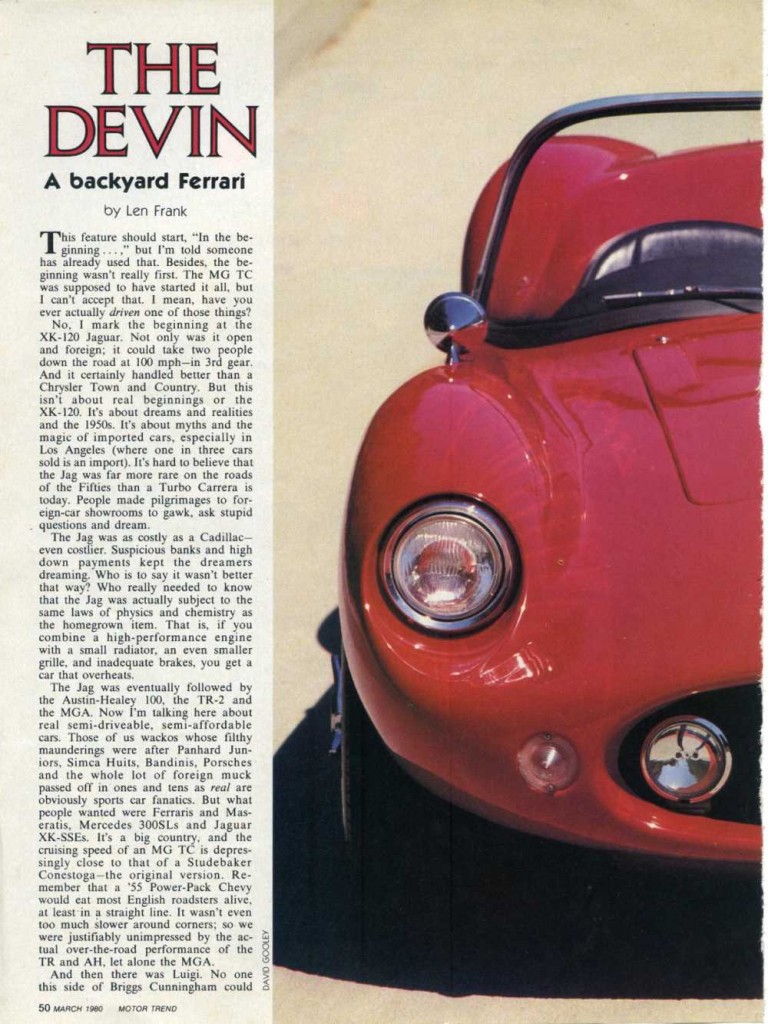

The Devin: A Backyard Ferrari

Motor Trend: March, 1980

By Len Frank

This feature should start, “In the beginning….” But I’m told someone has already used that. Besides, the beginning wasn’t really first. The MG TC was supposed to have started it all, but I can’t accept that. I mean, have you ever actually driven one of those things?

No, I mark the beginning at the XK-120 Jaguar. Not only was it open and foreign; it could take two people down the road at 100mph – in 3rd gear. And it certainly handled better than a Chrysler Town and Country. But this isn’t about real beginnings or the XK-120. It’s about dreams and realities and the 1950s. It’s about myths and the magic of imported cars, especially in Los Angeles (where one in three cars sold is an import).

It’s hard to believe that the Jag was far more rare on the roads of the Fifties than a Turbo Carrera is today. People made pilgrimages to foreign-car showrooms to gawk, ask stupid questions and dream. The Jag was as costly as a Cadillac – even costlier. Suspicious banks and high down payments kept the dreamers dreaming. Who is to say it wasn’t better that way?

Who really needed to know that the Jag was actually subject to the same laws of physics and chemistry as the homegrown item. That is, if you combine a high-performance engine with a small radiator, an even smaller grille, and inadequate brakes, you get a car that overheats.

The Jag was eventually followed by the Austin-Healey 100, the TR-2 and the MGA. Now I’m talking here about real semi-drivable, semi-affordable cars. Those of us wackos whose filthy maunderings were after Panhard Juniors, Simca Hits, Bandinis, Porsches and the whole lot of foreign much passed off in ones and tens as real are obviously sports car fanatics.

But what people wanted were Ferraris and Maseratis, Mercedes 300 SL’s and Jaguar XK-SSEs. It’s a big country, and the cruising speed of an MG TC is depressingly close to that of a Studebaker Conestoga – the original version. Remember that a ’55 Power-Pack Chevy would eat most English roadsters alive, at least in a straight line. It wasn’t even too much slower around corners; so we were justifiably unimpressed by the actual over-the-road performance of the TR and AH, let along the MGA.

And then there was Luigi. No one this side of Briggs Cunningham could afford him. Luigi was the surly, character in the odd coveralls who shook his head over the exotic Italian innards and never answered questions. I was really his car, you see, and you were only being allowed to use it with Luigi’s forbearance. Of course, Luigi had a cousin named Dieter, and another, Alf, and friends Olaf and Andre. American hands with four fingers and an opposable thumb obviously weren’t for the likes of metric or Whitworth tools.

We believed these things just as we believe in the dock strikes and currency fluctuations – the panoply of excuses that separated cars from owners and replacement parts. Something in this land of the entrepreneur, the cowboy capitalist, was sure to be done to help us realize our dreams.

If owning a Ferrari or Maser was too much trouble or cost too much, and since nothing was made here (don’t tell me about your T-birds and Corvettes), the only course left was to build your own. Briggs Cunningham did. So did Sterling Edwards. Or rather, they caused, at great expense, cars to be built that were aesthetic and visceral successes, after a fashion.

Reventlow’s Scarab was coming, but the Cobra half-domestic was still years away. A few guys squeezed Detroit engines into Healeys and usually got old doing it. Before going any further, a parable: The president of a large model airplane kit firm allowed that perhaps one in 10 or one in 20 of his kits was ever completed. It didn’t matter, though. The excitement was in the choosing, the anticipation; the fruition was in opening the box, spreading the parts, gazing at the plans. The kit, completed, would be a disappointment.

So the way was clear. The pragmatist got a job, saved his money and bought the compromise of his dreams. He got Dunlop wires instead of Borranis, a nice car instead of what he wanted. He settled. That’s why he was a pragmatist. Of course, not all pragmatists compromised. Some got rich, bought Ferraris and adopted Luigi and company.

Most bought Volvos and pretended that was what they wanted. But no everyone can handle practicality, even with dual SU carburetors.

A painful few weighed the merits of the new Warner T-10 4-speed. They looked at Dodge truck de Dions and gleefully checked Buick aluminum brake drums. If this seems parochial today, remember that the Nash-Healey and Cadillac-Allard made do with less and damn near won Le Mans to boot. The trickiest part had to be the body. No messing around here.

The body: A Chevy pickup with Maserati six in it is blasphemy, say the scriptures, an abomination to the eye. But a Chevy pickup chassis and running gear, suitable tweaked, with a Maserati body – now that has possibilities. You could botch up a chassis, but bending a sheet of aluminum over a barrel just didn’t cut it. To the rescue: fiberglass.

Magically, ‘glass body companies began to appear – Victess and Byers, Kellison and Alquist and Devin. Most of the offerings were clunk and clumsy, doing little or nothing to disguise the essential ’53 Ford underpinnings. But the Devin, now that’s another story.

The Devin:

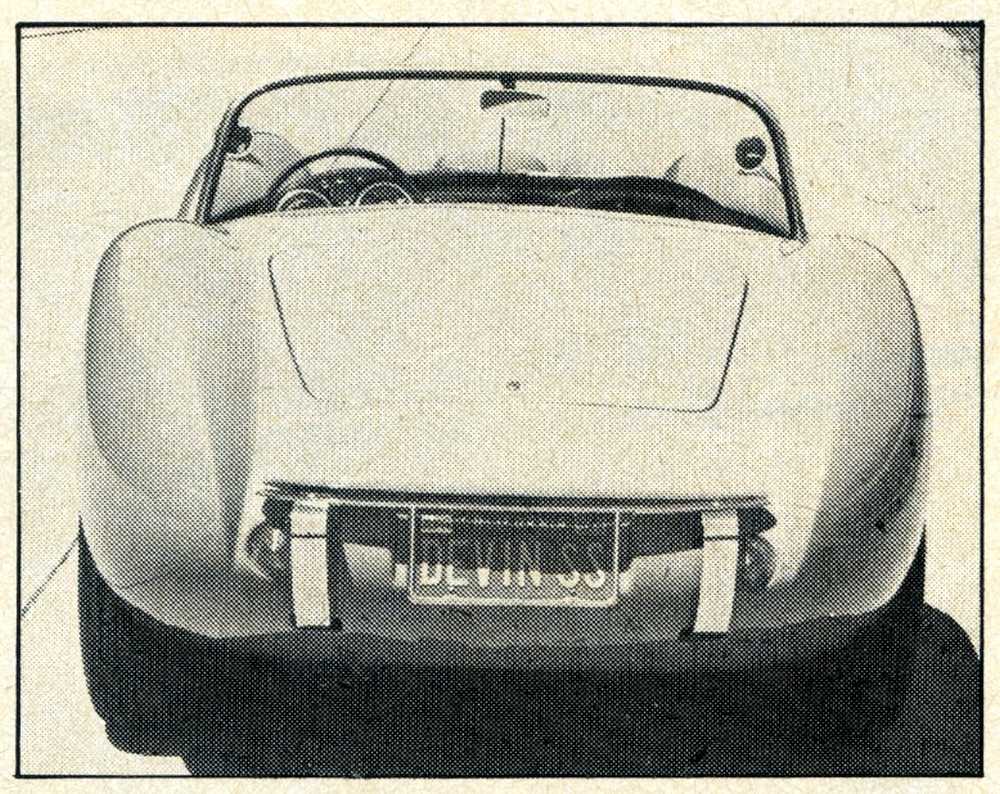

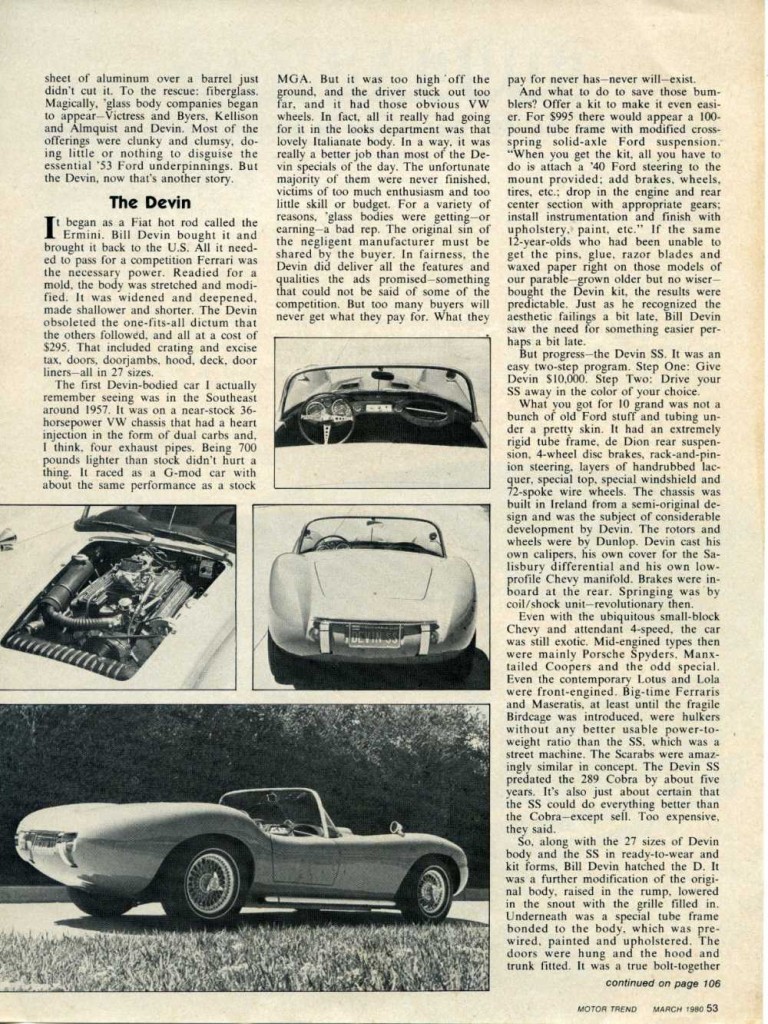

It began as a Fiat hot rod called the Ermini. Bill Devin bought it and brought it back to the U.S. All it needed to pass for a competition Ferrari was the necessary power. Readied for a mold, the body was stretched and modified. It was widened and deepened, made shallower and shorter. The Devin obsoleted the one-fits-all dictum that the others followed, and all at a cost of $295. That included crating and excise tax, doors, doorjambs, hood, deck, door liners – all in 27 sizes.

The first Devin-bodied car I actually remembered seeing was in the Southeast around 1957. It was on a near-stock 36 horsepower VW chassis that had a heart injection in the form of dual carbs and, I think, four exhaust pipes. Being 700 pounds lighter than stock didn’t hurt a thing.

It raced as a G-modified car with about the same performance as a stock MGA. But it was too high off the ground, and the driver stuck out too far, and it had those obvious VW wheels. In fact, all it really had going for it in the looks department was that lovely Italianate body.

In a way, it was really a better job than most of the Devin Specials of the day. The unfortunate majority of them were never finished, victims of too much enthusiasm and too little skill or budget. For a variety of reasons, ‘glass bodies were getting – or earning – a bad reputation. The original sin of the negligent manufacturer must be shared by the buyer.

In fairness, the Devin did deliver all the features and qualities the ads promised – something that could not be said of some of the competition. But too many buyers will never get what they pay for. What they pay for never has – never will exist.

And what to do to save those bumblers? Offer a kit to make it even easier. For $995 there would appear a 100 pound tube frame with modified cross-spring solid-axle Ford suspension.

“When you get the kit, all you have to do is attach a ’40 Ford steering to the mount provided; add brakes, wheels, tires, etc.; drop in the engine and rear center section with appropriate gears; install instrumentation and finish with upholstery, paint, etc.”

If the same 12 year olds who had been unable to get the pins, glue, razor blades and waxed paper right on those models of our parable – grown older but no wiser – bought the Devin kit, the results were predictable. Just as he recognized the aesthetic failings a bit late, Bill Devin saw the need for something easier perhaps a bit late.

But progress – the Devin SS. It was an easy two-step program. Step one: Give Devin $10,000. Step Two: Drive your SS away in the color of your choice.

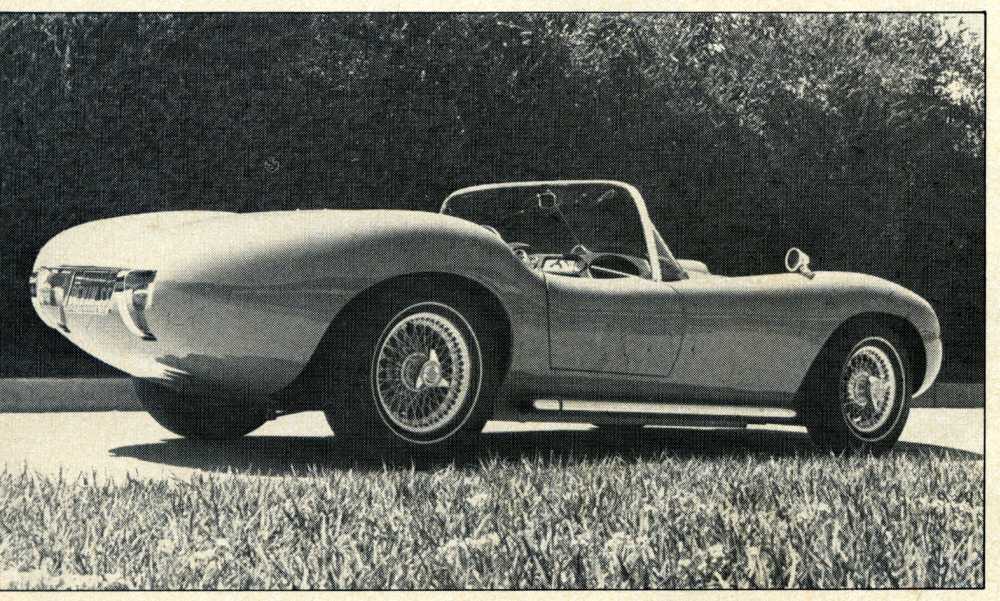

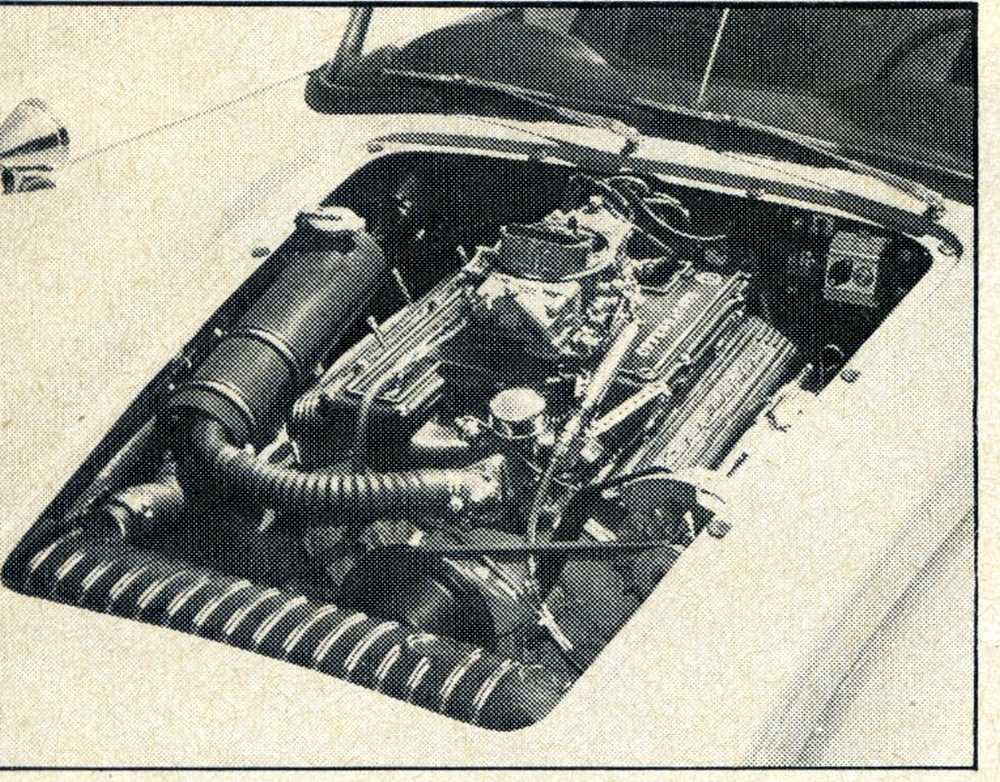

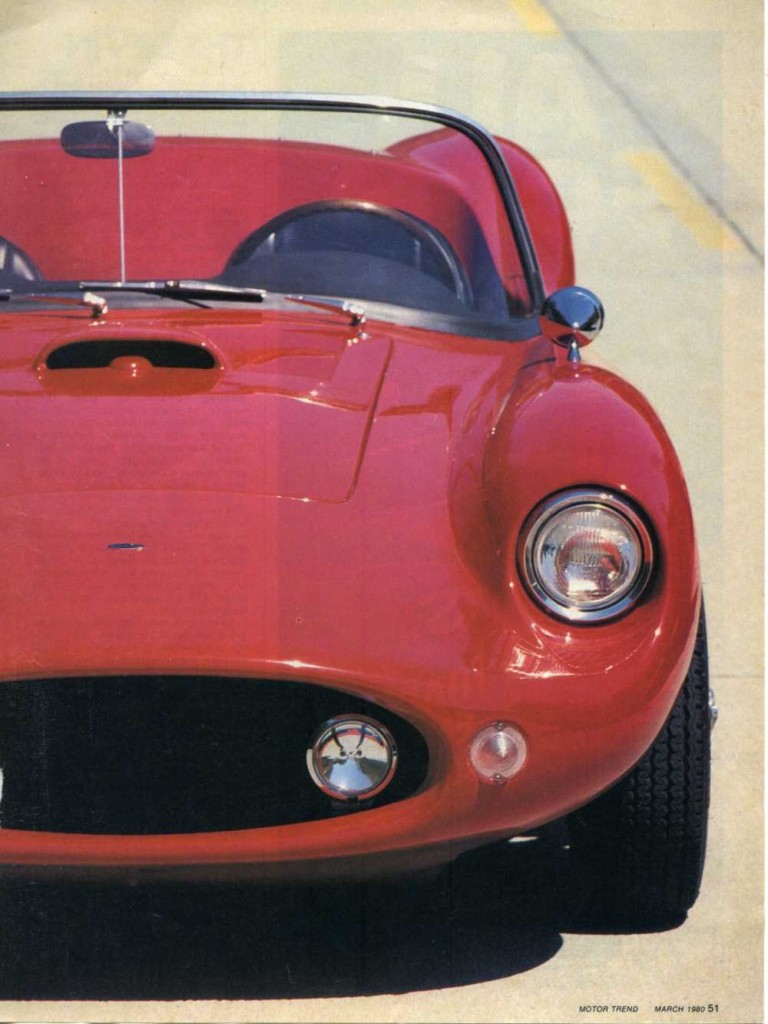

What you got for 10 grand was not a bunch of old Ford stuff and tubing under a pretty skin. It had an extremely rigid tube frame, de Dion rear suspension, 4-wheel disc brakes, rack and pinion steering, layers of hand-rubbed lacquer, special top, special windshield and 72-spoke wire wheels.

The chassis was built in Ireland from a semi-original design and was the subject of considerable development by Devin. The rotors and wheels were by Dunlop. Devin cast his own calipers, his own cover for the Salisbury differential and his own low-profile Chevy manifold. Brakes were inboard at the rear. Springing was by coil/shock unit – revolutionary then.

Even with the ubiquitous small-block Chevy and attendant 4-speed, the car was still exotic. Mid-engined types then were mainly Porsche Spyders, Manx-tailed Coopers and the odd special. Even the contemporary Lotus and Lola were front-engined. Big-time Ferraris and Maseratis, at least until the fragile Birdcage was introduced, were hulkers without any better usable power-to-weight ratio than the SS, which was a street machine.

The Scarabs were amazingly similar in concept. The Devin SS predated the 289 Cobra by about five years. It’s also just about certain that the SS cold do everything better than the Cobra- except sell. Too expensive, they said.

So, along with the 27 sizes of Devin body and the SS in ready-to-wear and kit forms, Bill Devin hatched the D. It was a further modification of the original body, raised in the rump, lowered in the snout with the grille filled in. Underneath was a special tube frame bonded to the body, which was prewired, painted and upholstered. The doors were hung and the hood and trunk fitted. It was a true bolt-together proposition, simpler by far than, say, a Lotus Seven. All special parts and any stock parts that required modification were included in the kit.

Weight was in the 1200 pound region so that, even with stock VW power, performance was passable. And, of course, a pushrod Porsche fit right in. A bit later came the Devin C – the same thing but with a Corvair drivetrain. Even with the puniest Corvair, double the VW horsepower could be counted on with only a 150 pound weight gain.

And remember that the Corvair offered the first production turbo (150 horsepower, later upped to 180). Devin’s brochure claimed 250 potential horsepower, 0-60 in 4 seconds, top speed of 150. For the genuinely inept, Devin would arrange to have the kit assembled by a local buggy shop for $50 – $75.

By 1963 it was about over. Devin built one last car, an SS coupe that used a Stingray windshield. Shown at the New York Auto Show, it was a smash. Orders came in, but the financing to build the car wasn’t there. Perhaps two dozen kit-body companies had failed before Devin. About a dozen more after. Too many kit cars started out badly financed, poorly conceived, ugly and unworkable.

Unlike the Devin process, the customer was required to become a professional scrounger – a junkyard adept. As with those model airplane kits, the satisfaction was too often only in anticipation. People sued and got sued. Bodies sometimes came late – and sometimes not at all.

To the flint-hearted bankers, the Devin was just another high-risk piece of fiberglass. Despite years of production, experience, engineering and pioneering, Bill Devin was perceived to be one of those fast-talking (well, really slow-talking) con men. And so Almquist and Atlas and Byers and Meyers an Victress, LaDawri, Fiberfab and sure, Devin, all disappeared.

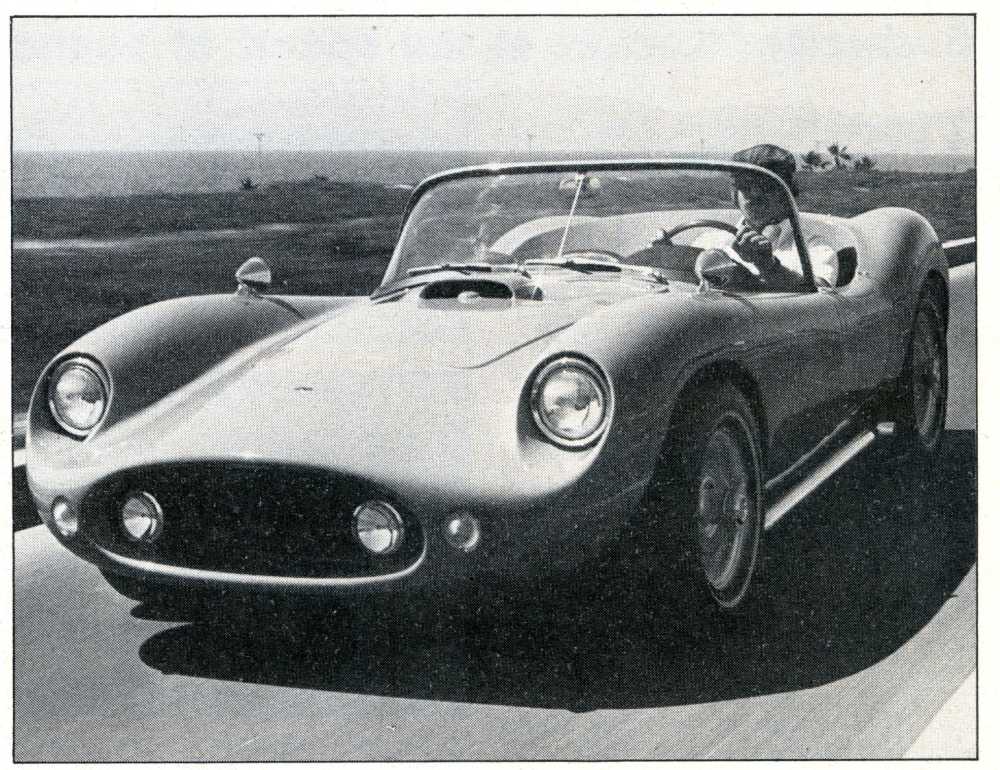

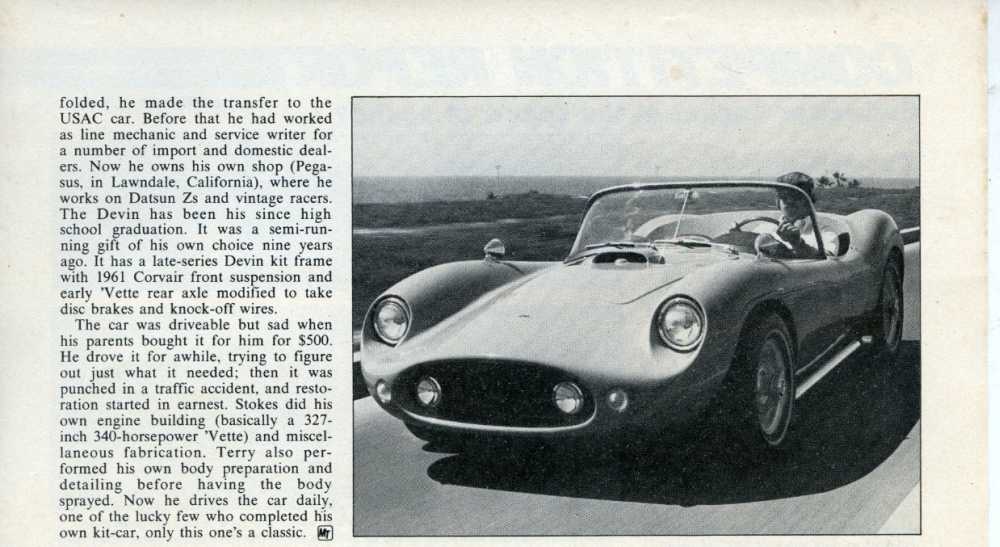

Terry Stokes, the owner of the car shown here, is just another car-crazy Californian – with one or two additions. When he was younger, just a kid really, he worked his way up to the number two spot on the Vels-Parnelli F5000 (Andretti) car. When that effort was folded, he made the transfer to the USAC car.

Before that he had worked as line mechanic and service writer for a number of import and domestic dealers. Now he owns his own shop (Pegasus, in Lawndale, California) where he works on Datsun Zs and vintage racers. The Devin has been his since high school graduation. It was a semi-running gift of his own choice nine years ago. It has a late-series Devin kit frame with 1961 Corvair front suspension and early ‘Vette rear axle modified to take disc brakes and knock-off wires.

The car was driveable but sad when his parents bought it for him for $500. He drove it for awhile, trying to figure out just what it needed; then it was punched in a traffic accident, and restoration started in earnest. Stokes did his own engine building (basically a 327 inch 340 horsepower ‘Vette) and miscellaneous fabrication.

Terry also performed his own body preparation and detailing before having the body sprayed. Now he drives the car daily, one of the lucky few who completed his own kit car, only this one’s a classic.

Summary:

I like the article – it grows on me over time. And the author – Len Frank – certainly had a distinctive writing style. Click here if you would like to learn more about Len Frank and his background in automotive journalism.

There was another section of this article – a sidebar on Bill Devin – which I’ll share in the near future here at Forgotten Fiberglass.

Hope you enjoyed the story, and until next time…

Glass on gang…

Geoff

Someday I hope to transcribe the tapes of a conversation Harold had with Bill Devin when we picked up our uncompleted SS from him in California. Over several days Harold recorded many hours (part interview, mostly conversation) as they talked about Bill\’s cars and that time in the car industry. Of course some of the information was used in articles Harold wrote about Devin (the cars and the man), but there\’s bound to be more tidbits of information on those tiny little tapes. Harold had all that info in his head, but maybe someday I\’ll be able to share the interviews. Hope so.Shelley

Thank you Shelley – and we’ll be hear to help transcribe and share that information when you are ready. Harold will be truly missed but we will keep him with us in everything we do – always…..Geoff

I like the article too. The Devin was one classy design. I always liked Italian styled cars the best.

Mel

I have always thought this was an interesting article. Bill Devin told me he only built three Devin SS models with the Corvair front suspension and live rear axle, but I suspect he built many more of them. He called them an SS at the time, trading on the reputation of the earlier Irish and California-built Devin SS models with DeDion rear end, fabricated IFS and Girling disc brakes. As far as I know all of the live axle cars were sold in kit form. There was a photo of one on the old Devin web site that Bill had, showing an SS kit car ready to be shipped with drum brakes all around. Bill also told me he sold three versions of this SS model with Corvair front suspension and a Pontiac Tempest transaxle/swing axle rear suspension setup (and Chevy V8 in front). Never saw or heard of one.

Best wishes,

Harold Pace

1959 Devin SS

In the back of my mind when I see a nice car, I pretend to park it next to a Ferrari 118 LM. Then I decide how it matches up.

You can park the Devin next to my imagined Ferrari anytime. Most people would think both are Ferraris.

Hi Les…disagreement is good However…keep in mind the mission you, I, and all of us face. We are ambassadors of these cars and their history. And for 50+ years only disparaging remarks, scoffs, and negative comments have been banded about concerning these cars and their history. And for the most part these remarks were right.

However…keep in mind the mission you, I, and all of us face. We are ambassadors of these cars and their history. And for 50+ years only disparaging remarks, scoffs, and negative comments have been banded about concerning these cars and their history. And for the most part these remarks were right.

But there were many many beautiful and well-built cars done including examples of Glasspar, Victress, Woodill, Meteor, Byers, Grantham Stardust, Devin, and Kellison. To this point, we are bringing a factory built Meteor SR-1 to Amelia next year which is in mostly original condition. This would stand up to any well-built automobile from this era – which you’ll see as you’ll be with us at Amelia, 2015 too

There were many beautiful examples built – and built right. This is what we need to celebrate while also giving a nod to ones not fully built too.

We – all of us – need to lead with the positive each and every time. And of course all of us would agree – most were not fully built, many were not well built but many were built beautifully. If we lead with all conversations about the negative then we are not acting as ambassadors and educators of this wonderful genre of cars. You’re just getting in line with the conversation of 50+ years. Those years are over.

Getting people to see the beauty of what was created – at its best – and what has been restored – at its best – is our focus.

No one would disagree with the negativism you mention in the article – and I admitted that in my posting of the story. But that’s the old story told for 50+ years. Our new mission leads with positive information and discusses what was – and wasn’t accomplished – in the past.

So think of yourself as an ambassador of the wonderful story of Kellison and other marques – people will celebrate the accomplishments of what was done in the past if you and all of us take this approach.

Just my thoughts gang.

Geoff

Geoff:

What I meant was that most builders of fiberglass bodies in the 50s & 60s grossly underestimated the abilities of their buyers and also the time required to complete a car. No doubt a number of exquisitely finished cars were produced, but many, if not most, seem to have disappeared in the last 50 years. We regularly race against Devins, and other “kit” cars from the 50s and 60s, and we always we query their drivers/owners about their car’s history. I think of the 10 or so “kit” owners with whom we’ve talked only two or three claimed to have competition credentials from the sixties. The majority have histories like our Kellison – half completed or poorly completed cars that required almost total rebuilds.

We’ve applied for FIA credentials for our Kellison & we cannot find a single record of any Kellison competing as a race car in the 1960s. There were a few Devins, but that seems to be all.

If you follow the auction scene you will also see a number of fiberglass-bodied cars from the 50s and 60s with quite recent completion dates.

I think our Kellison is a good ambassador for the 50s fiberglass body manufacturers – both as a race car ans as a show car.

Les

Wow what a article , the writer seems angry while he’s writing the first part then lightens up a little , he must of built a few of these cars himself, it can be frustrating , I’ve made changes in my Glasspar so many times i could have finished two cars, you get something done and realize something else would be cooler or function better, the main thing is you love the car and it becomes a labor of love, the reason you change things is because you seek your level of perfection and with every small accomplishment comes a great amount of satisfaction.

Sorry to disagree with you but the negativism in the article is well deserved/documented. Just look at Kellison, who lasted a lot longer than Devin. Hard to determine how many Kellison bodies & their derivatives sold – probably somewhere in the 1500 range (forget claims of up to 3000.) The Kellison registry has about 150 members with perhaps 75 cars listed, of which there probably aren’t more than 30 completed & running. As someone who took a shoddily completed & totally unusable Kellison to what it is today – a truly beautiful & dependable dual use car – I can testify how difficult it was, and is, to complete one of these 50s/60s fiberglass cars.

So far this racing season, the ONLY car to complete every weekend of vintage racing is the Kellison.

Keep up the old articles – love them!

Les