Hi Gang…

Today I’m honored to share an article by our friend and intrepid “historian-adventurer” Bob Cunningham. Bob has always had an affinity for small cars and their history and this story is about a different “BMW” than you’ve heard of – a company called “Boulevard Machine Works” out of California.

So let me bid “adieu” and hand off today’s story to Bob.

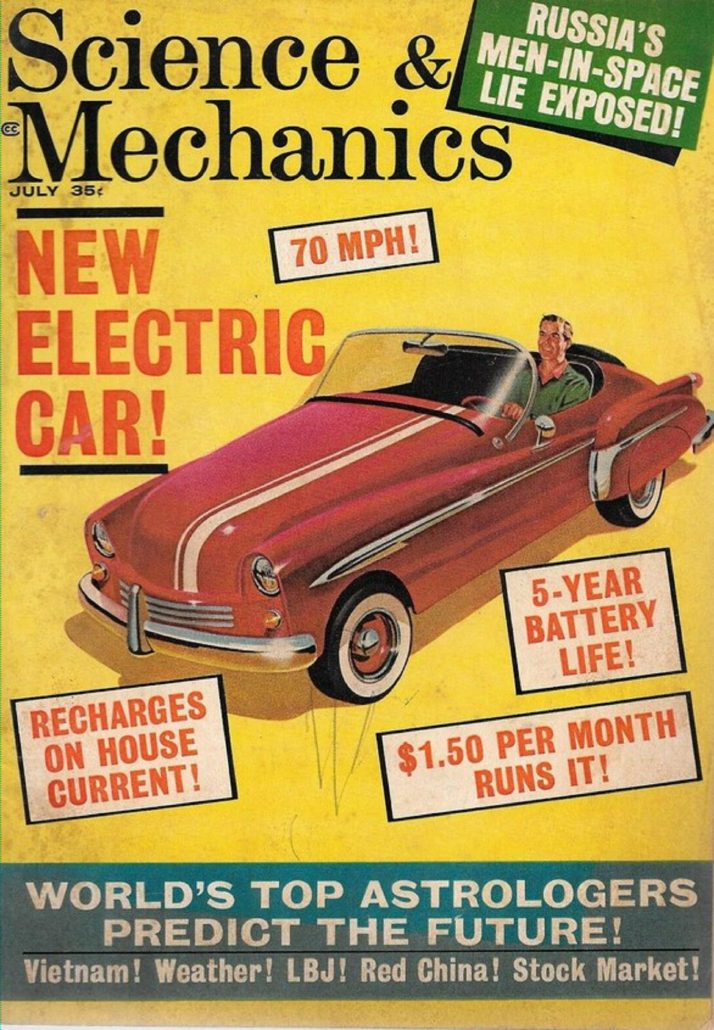

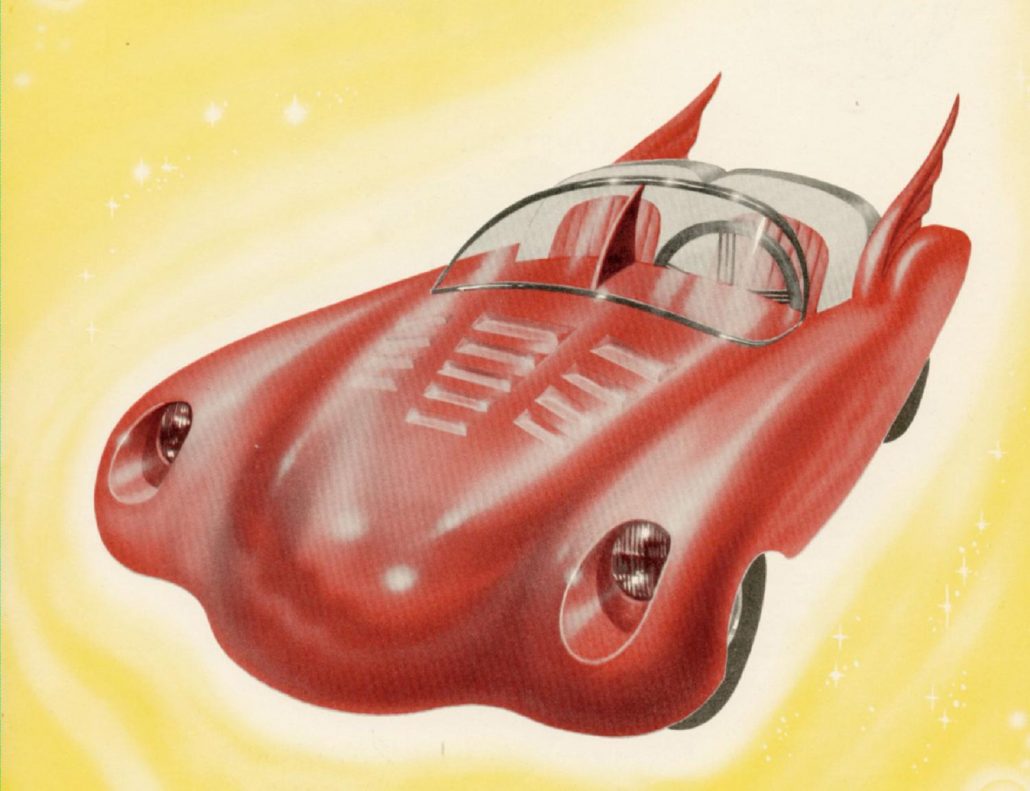

Science & Mechanics magazine featured an artist’s rendering of BMW’s proposed up-sized model that would have been built to the same dimensions of popular English sports cars. It was also featured in the February 1957 issue of Motor Life.

Electrified Cuties From The “Other” BMW

The Forgotten Electric Cars of Hollywood’s Boulevard Machine Works

By Robert D. Cunningham

FUTURISTS HAVE LONG PREDICTED the arrival of the economical, efficient and attractive electric automobile. Until valiant and noteworthy efforts spearheaded by Toyota on the low end and Tesla on the high, the dream remained elusive due to the relatively low price of fuel and high cost and inefficiency of traditional batteries. Even so, favorable conditions have existed from time to time.

In 1900, steam, electricity and gasoline were powering horseless carriages in relatively equal numbers and dozens of manufacturers provided reliable, quiet and efficient electrics. Of the 4,192 American cars built that year, 28% were electric. Ironically it was an electric apparatus that doomed the electric car— the electric starter for gasoline engines. The self-starter made cars easier to use and more accessible to those without the physical strength to crank their vehicles.

BMW decals were applied to the car’s rear decks behind the seat back. The letters “BMW” stood for Boulevard Machine Works, and the letters “PL” were Leslie Perhac’s initials.

In February 1942, United States automobile production was curtailed as manufacturing efforts shifted toward supporting our troops overseas. Three years later, when peace brought an immediate need to replace the nation’s aging passenger car fleet, the cost of gasoline had tripled and the price of electricity had declined by two-thirds. Automobile owners had driven the rubber off of their tired old relics and they were ready to buy almost anything new. So electrified golf carts, which had first emerged in Kansas City and Long Beach almost simultaneously during the 1930s, took to the streets to exploit their obvious economic advantages.

By 1950, the golf carts had evolved into two-passenger Autoette, Mobilette, Electric Shopper, Marketour, Marketeer and other grocery-getting “automobiles” that could operate cheaply and travel useful distances on a charge. Even the crudest of vehicles managed to find buyers. But one Hollywood inventor/entrepreneur took a different approach. His electric cars looked like, well, cars.

Leslie Perhacs was born in Budapest, Hungary in 1898 and immigrated to Studio City, California during the 1920s. He established his 12,000 square-foot research and development workshop in nearby North Hollywood on the corner of Burbank and Vineland Avenues. Perhacs called his place Boulevard Machine Works—BMW for short. There he developed and sold a wide variety of electric vehicles, including golf carts, boats, cycles, amusement park rides, and vehicles especially suited for paraplegics.

In 1949, Perhacs began limited manufacture of a licensable electric car called the BMW Boulevard 4-wheel-drive roadster. It was powered by a series of three-cell, 24-volt storage batteries and four 1/6-horsepower electric traction motors installed at right angles over the axles. Equipped with his patented gear system that stopped or reversed the car without damaging the power plant, the Boulevard required no conventional transmission or differential.

Styling loosely mimicked the contemporary Buick Roadmaster with its bulbous front fenders that swept across the sides to meet skirted fenders at the rear. An optional wrap-around chrome bumper was available for commercial models. Perhacs’ son, ten-year-old Les Jr., piloted a four-wheel-drive BMW Boulevard in Pasadena’s 1950 Rose Parade.

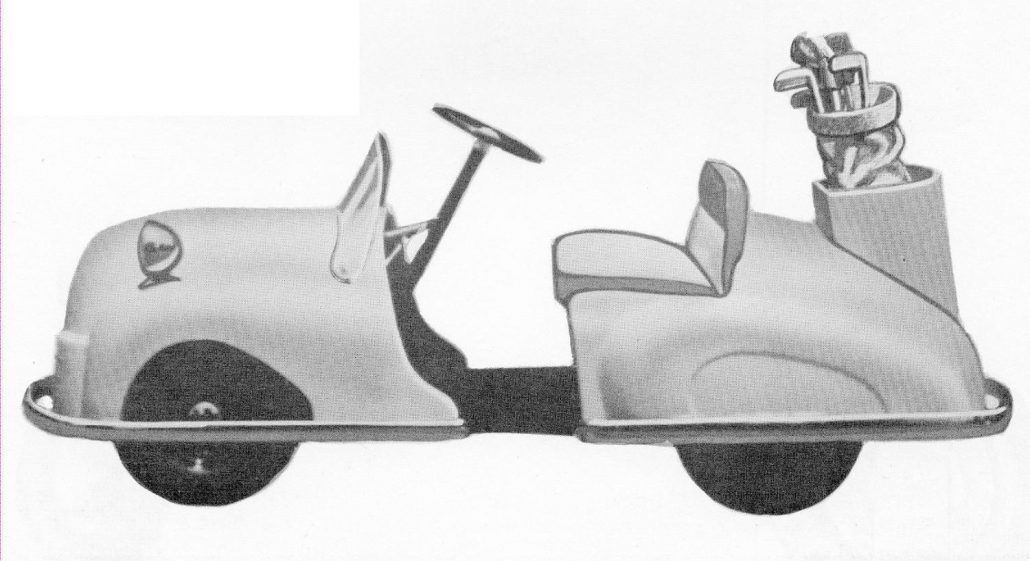

Buyers could also choose the BMW Errand Master. With its two chrome strips and headlights perched on top of the fenders, the two-place, 48-inch-wide Errand Master smiled at oncoming traffic. The doorless body allowed step-through entry and exit, perfect for veterans and paraplegia victims. The fiberglass body, which was hinged in back, lifted to expose the batteries, motors, and the built-in recharger. An optional golf bag holder converted the Errand Master into a stylish golf cart.

Perhacs marketed his cars to young adults as entry-level sports cars, although their governed top speed was only 25 miles per hour. A single charge was good for up to 75 miles with operating efficiency of up to 300 miles at a cost of just 39 cents. Batteries were good for up to five years as long as Perhacs’ patented secret electrolytes were changed every other year. He claimed the chemical greatly reduced corrosion of the metallic plates.

By 1955, Perhacs had added two golf cars and a parcel truck to the BMW line at a time when the public considered an electrical automobile as a novelty rather than an environmental asset. When Les, Jr. asked why BMW was building electric cars when cheap gas was available on nearly every corner, Leslie, Sr. wisely replied, “Sooner or later we’re going to run out of fossil fuel.”

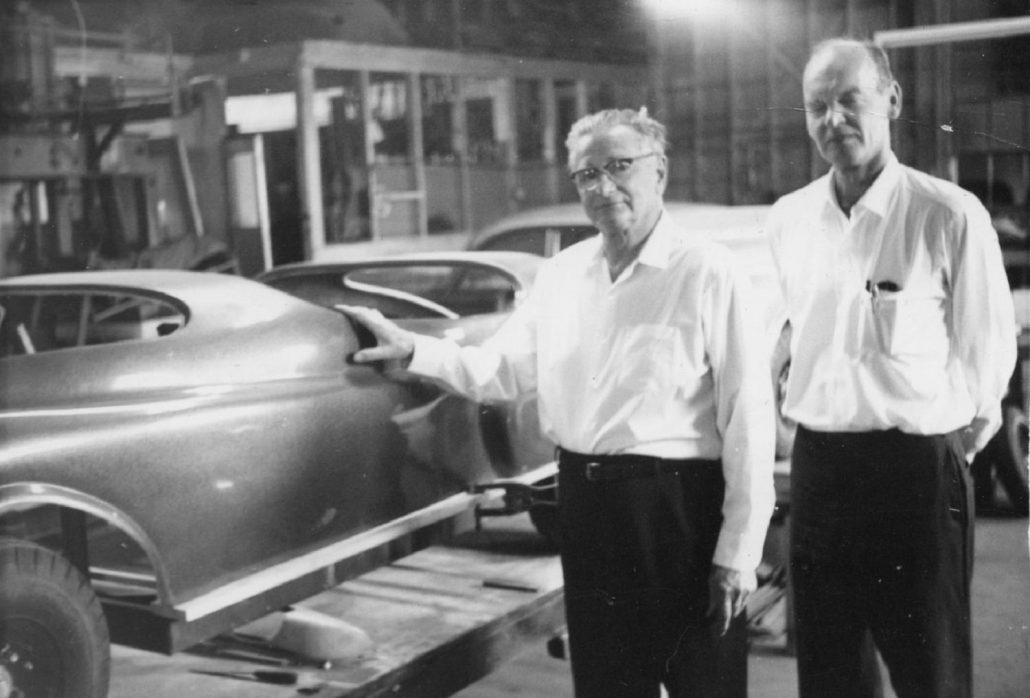

Styling began when Sr. and Jr. sketched their ideas on paper. Full-scale plywood mock-ups were covered with plaster, carved into shape and overlaid with fiberglass. Perhacs, Sr. generally worked alone, but he hired temporary help to lay fiberglass and prepare bodies for painting. To expedite the process, he developed one of the first spray-chopping fiberglass guns. If a finished car didn’t sell immediately, Perhacs Sr. either dressed it up with additional trim or removed parts to use on his next project. As a result, few of the first year’s output of 25 Boulevards and Errand Masters were exactly alike.

Les Perhacs, Jr. was a talented teenager when he conceived several new product designs for his father’s organization, including parcel carriers, futuristic bubble-canopied cars, and a sports car called the Starfire, which graced the 1956 Boulevard Machine Works product brochure cover. Text touted “the beautiful car perfected after 10 years of experimental engineering.” At 140 inches long and 70 inches wide, its dimensions were roughly the size of a Volkswagen Beetle. Mechanical features included direct four-wheel-drive and hydraulic brakes on each wheel, and split wheels allowed for 5-minute tire changes. Its $1,887 price was competitive in the small-car class, but its top speed of 50 miles per hour and absence of weather protection likely kept customers away.

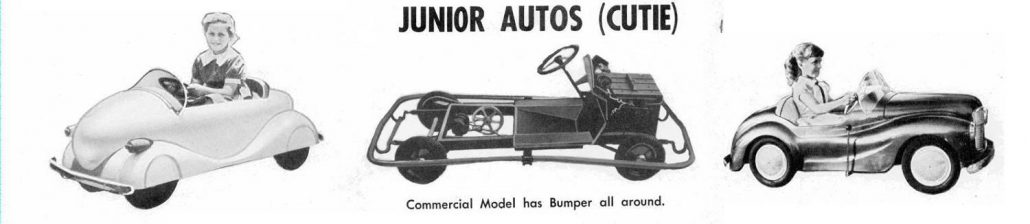

The fantastically tail-finned Starfire was never built, but the half-scale Starfire Jr. for children was, setting a doting father back $600 for the single-motor model and $750 for the two-wheel-drive, 25 mile-per-hour version. Additional Jr. models included the $575 two-passenger tandem Cutie on a 60-inch two-motor chassis, and the $395 single-passenger, single-motor Cutie Jr. Clients who bought BMW’s Junior autos included members of the Shipstads & Johnson Ice Follies, motion picture studio executives and movie stars. Walt Disney visited the shop frequently.

At age 16, Leslie Jr. won a scholarship to Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles and later attended the USC Art Center School of Design and Pratt Institute in New York. While at USC in 1962, he won the National Alcoa Aluminum Student Design Award for his ‘tractor for the sea’, a battery-powered diving saucer that he developed for Hobie Cat. After college, he went to work as a model maker and inventor for the Toy Development Center in Los Angeles where he designed toys, games and studio props for Universal Studios’ Star Trek and The Man from U.N.C.L.E. television series.

Meanwhile Perhacs, Sr. update the BMW Boulevard by incorporating headlights within the front fenders. The new 4-wheel-drive Electricar with a 2-horsepower motor on each wheel could zip around Los Angeles at speeds of up to 70 miles per hour. Eight 3-cell, 48-volt lead-acid batteries were responsible for fully one-third of the car’s 1,000-pound curb weight. Six batteries were mounted in front behind a plywood firewall and the other two were situated behind the pleated bench seat.

Although the Boulevard Machine Works Electricar was economical to operate at a cost of less than $1.50 a month, $2,300 was a steep price to pay for the tiny roadster (although one client instructed Perhacs to trim his Electricar with gold plating valued at $53,000).

In a July 1966 Science & Mechanics magazine interview, Perhacs claimed he could develop a family-size BMW Electricar two feet longer than his 10-foot production model that would rival the speed and efficiency of gasoline-powered cars at a fraction of the purchase price. The better known BMW (Bavarian Motor Works) of West Germany took notice and formally objected to his use of their initials for car-building. Perhacs renamed his business Perhacs Motor Works (PMW), concentrated on electric golf car production, and set his sights on more innovative projects.

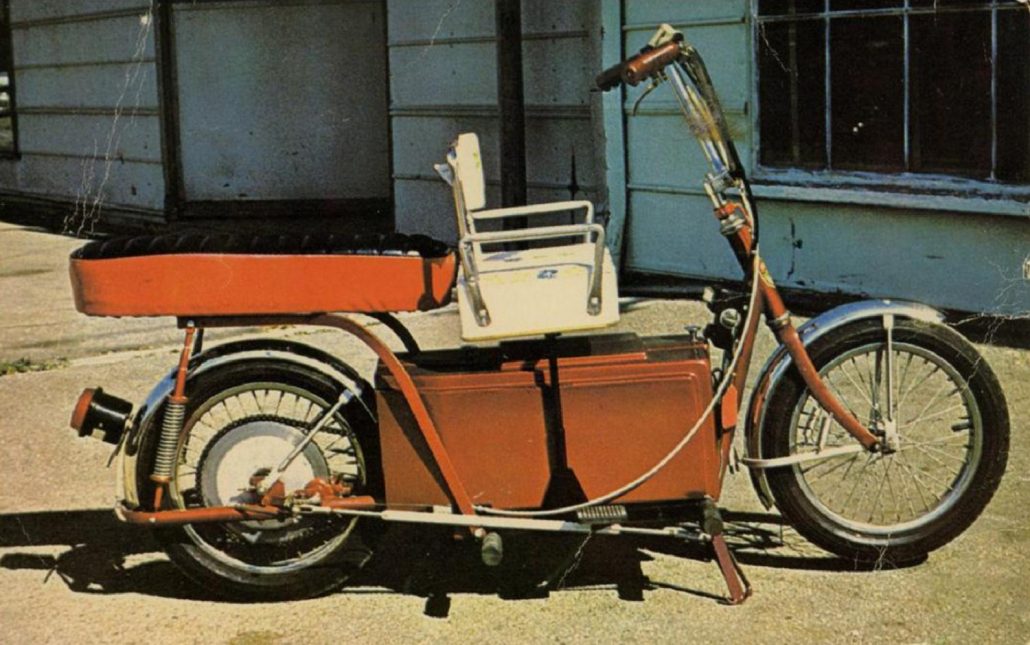

After Perhacs changed the company name from BMW to PMW (short for Perhacs Motor Works), he introduced the Elestra Electric Motorcycle, “suitable for all age groups for pleasure or business riding, one answer to end noise and air polution. Designed for street use, not as ‘trail bikes’. 12 and 24 volt systems with built-in battery charges and intermittent duty motors. Elestra-J for young ones and adults. Speeds up to 20 mph, range 30 – 40 miles. Elestra-S for all riders, speeds up to 30 – 35 mph, range 40 – 60 miles.”

For example, he consulted with renowned architect Victor Gruen on a series of neighborhoods in which residents’ necessities would be within the reach of a fully charged Electricar. He conceived a portable battery pack that the driver could easily switch out at thousands of battery stations. And he experimented with a unique spring drive propulsion system—as a car’s spring wound down during operation the battery motor would rewind the spring.

It might of appeared that Perhacs was in a perfect position to benefit from the Clean Air Act of 1970, which required every state to stem pollutants. When the OPEC oil embargo of 1973 created long lines at the gas pumps, consumers demanded an economical, efficient and attractive small car. But the timing was off for Leslie Perhacs. The passionate promoter of electrified transportation fell ill late in 1974 while finalizing an automobile development contract in Japan.

While in high school in the early 1960s, Leslie Perhacs, Jr. contributed to his father’s business by designing a series of futuristic electric vehicles. Although his father built none of these designs, Perhacs Jr. grew to become an accomplished inventor and sculptor in his own right.

He returned to Los Angeles and survived an aortic bypass but a blood clot took his life on the day he was to return home. Immediately the Japanese company claimed and retrieved valuable equipment from PMW. In 1975 the facility was auctioned off in lots that included $250,000 worth of real estate, machinery, patents, storage batteries, tools, parts, raw materials and, of course, whatever remained of Perhacs’ unique and innovative inventory of electric vehicles.

Where are the remaining examples of BMW’s electrified Cuties today?

Let’s Explore More Vintage Photos That Bob Cunningham Sent In:

Four-wheeled BMW Golf Car was available in one-passenger and two-passenger models priced at $680 and $1,195 respectively.

The stylish BMW Errand Master roadster was advertised as an ideal second family car or runabout for paraplegia victims. The car measured 102 inches long, 48 inches wide, and carried two passengers at speeds of up to 25 miles per hour. Suspension featured coil springs and shock absorbers. Buyers could select from a range of colors and paid between $975 and $1,250.

Leslie Perhacs Jr. drives the all electric 4 wheel drive Boulevard in the 1950 Rose Parade under the watchful care of his father, Leslie Sr.

The popular Cutie for youngsters under 12 years of age was available in two models. The single-seat version was an original Perhacs design, and the two-seater looked much like the English Austin J40 pedal car.

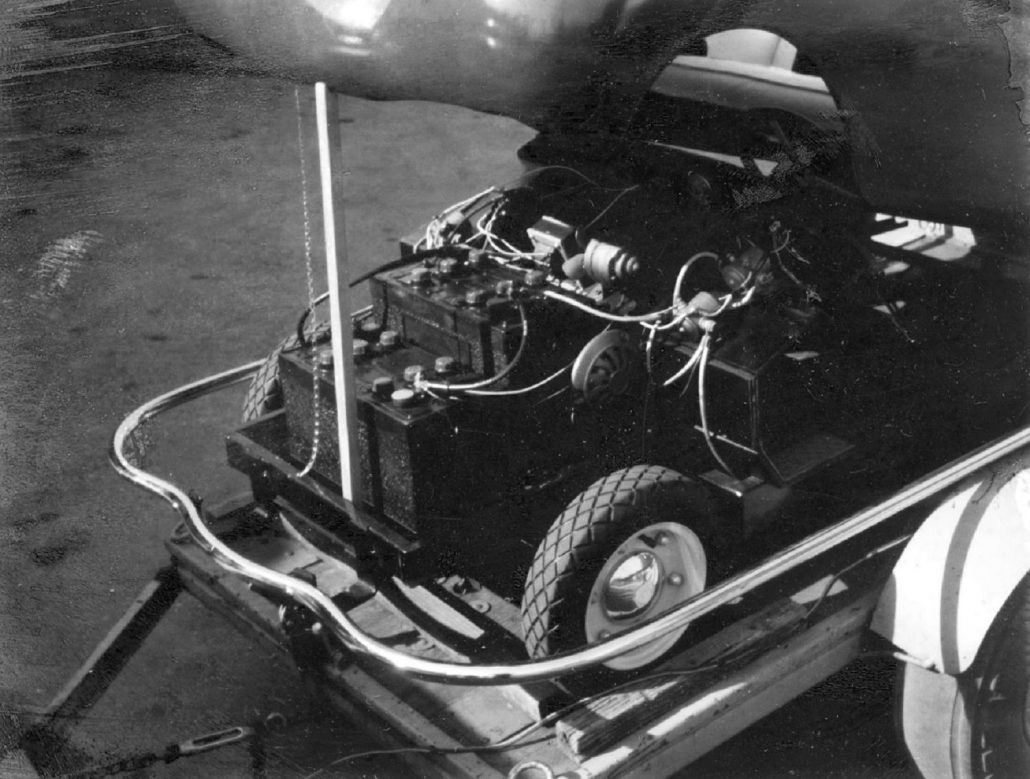

Access to the BMW Electricar’s series of 3-cell storage batteries simply required lifting the hinged body. To recharge, the owner unreeled an extension cord from under the dash and plugged it into a standard 110-volt outlet.

One of Perhac’s BMW cars on a trailer with the body raised, showing the chassis with batteries, solenoid, and other electronics.

Leslie Perhacs test driving a three-wheel parcel delivery version of his Elestra Electric Motorcycle in 1954.

Summary:

It sounds like there should be several of these “BMW’s” around today, but Bob has not been able to locate any. Sounds like a job for our Undiscovered Classic aficionados out there. Anyone want to help start the hunt?

Thanks again to Bob Cunningham for sharing this story today with us at Undiscovered Classics. If you want to learn more about Bob and view some of his writings and work, explore the links below:

Click here to view Bob Cunningham’s stories on Undiscovered Classics

Click here to view Bob Cunningham’s art and other items in his store for sale

Click here to view Bob’s book on “Orphan Babies – America’s Forgotten Economy Cars” via Amazon

Hope you enjoyed the story, and remember…

The adventure continues here at Undiscovered Classics.

Geoff

The American BMW (and later PMW) appear to be a line of cars that the world has forgotten. The only reason that I heard about them was because I discovered a Science and Mechanics magazine from July, 1966, covering the “NEW ELECTRIC CAR!”… They cleverly failed to mention the size and stature. I appreciate the author for bringing all of this information together and creating an informative place for people to learn about Leslie Perhacs great work!

Please contact me. My mother used to work for Les when I was a child. What else can we tell you? The Japanese were horrible to Les. I have several postcards addressed to my family from Les when he was in Japan. Les gave me a pink electric car to drive when I was a child, and a scooter that o rode to death, however I don’t know what happened to either. Les also made my cousin who had MD an electric wheelchair before they were popular. I also have a wrought iron butterfly sculpture made by Les Perhacs Jr that I’ve had since I was a child. Les was very dear to our family.

Since all of the vehicles in the Rose Parade are covered in flowers and vegetation my guess that this picture was taken in the Junior Rose Bowl Parade which was led by the Whitehead Special around 1947.

Not only was the BMW name borrowed from the Bavarian carmaker, but the Cutie kid’s car had styling clearly derived from the hyper-classy Austin J40 pedal car. Since the first German BMW cars were British Austins built under license, this makes the pilferage sort of poetic.