Hi Gang…

I love first person accounts of history – and this one’s an early review of the history of Kurtis-Kraft – from 1952 no less. Talk about early!

This article appeared two years before the ’54 introduction of the fiberglass Kurtis 500M sports car, was on the heels of Kurtis’ earlier successes with sports and race cars, and covered this in detail I’ve never seen before. While I’ve found many articles about Kurtis and his cars from 1947 thru 1952 and beyond, this is one of the earliest I’ve located that discusses the history of Kurtis, and for that….I’m very excited about sharing it with you here at Forgotten Fiberglass.

One of the neat things about this article is that it articulates in detail the story about how the Kurtis-Hughes sports car came to be in the late ‘30s / early ‘40s – and some of its history thereafter. This is one of my favorite cars, and I’ve not seen this detail before.

Today’s article is long – with only 3 pictures. So if you’re a Kurtis fan like myself – you’ll love it. If not… well…. now’s the time to start and dig into some detail that few have seen before.

And with that….off we go!

Kurtis Kraftsmanship

Auto Sport Review, May 1952

A few years ago Kurtis sneaked one of his cars out on California’s Muroc dry lake test course and pushed his foot to the floor board. When he’d flashed over the course at 130 m.p.h., and rolled back to the starting line, an old time driver rushed out and soundly berated him. You’re too valuable to racing to risk your fool neck,” the driver scolded. Since then Kurtis has been side-lined.

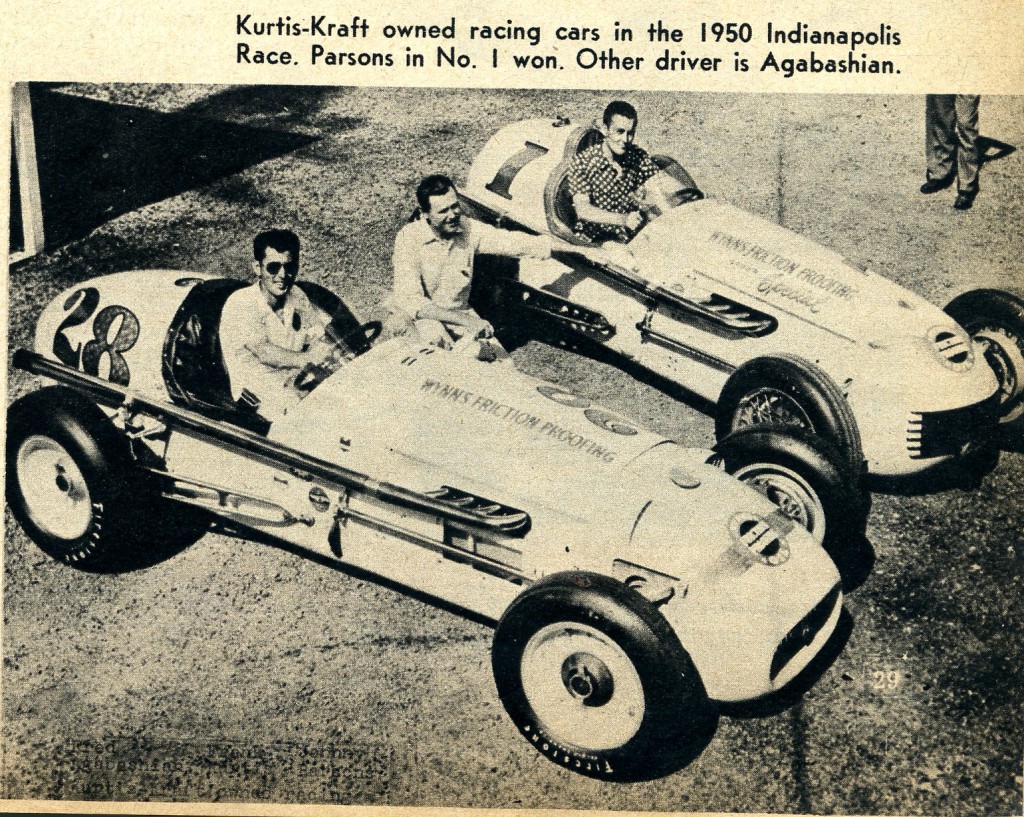

Kurtis designed a tubular-trussed chassis for the Indianapolis 500-miler while drivers and fellow designers sneered. They took one look at the car’s tubular frame–its cross members resembling bridge construction–and its independently suspended wheels and predicted it would sway like a suspension bridge. They promptly dubbed it “The Brooklyn Bridge.” But when Johnny Parsons romped home in it with the “AAA” National Championship in 1949 and won at Indianapolis last year, one driver who had pooh-poohed the car swallowed his words as the checkered flag waved Parsons in on Decoration Day.

“That’s one ‘Brooklyn Bridge’ I’ll buy,” he winced. He wouldn’t have gone wrong. The Kurtis “Brooklyn Bridge” collected $58,000 in tolls at Indianapolis alone last year. In the process Parsons smitherined all track records from 100 to 345 miles when rain stopped the marathon. Parsons averaged more than 126 m.p.h. for some laps.

Since 1946, Kurtis has built 28 Indianapolis big cars–almost half of the post-war 500 milers. But there was hardly a car in last year’s race that didn’t carry some Kurtis-Kraft part. Of the 28 Kurtis-built cars entered in the Indianapolis field of 60, seventeen qualified and five ran away with the race, taking five of the first 10 places, including first, fourth and fifth. Kurtis cars came away with a whopping hunk of the $175,000 prize money.

Beneath his racers’ functional skins, Kurtis stuffs that vital organ–usually an Offenhauser racing motor. Race driver Lou Meyer manufactures the Offys at his Meyer and Drake Engineering Co., a few miles from Kurtis’ Kurtis-Kraft Co., in Los Angeles, racing capital of the U.S. A Kurtis body and an Offy motor are as American as ham and eggs. No real fan of racing ever hesitates when someone asks, “Which one has the Kurtis?”

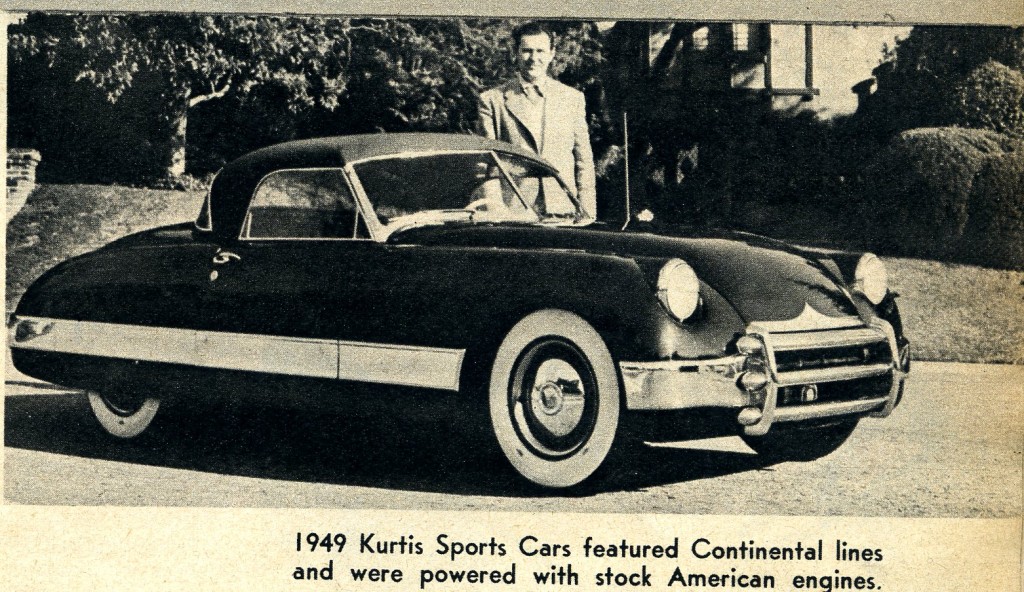

As someone said recently, “If Frank wanted to exploit his Kurtis-Kraft sports car as others did–he’d be a millionaire tomorrow morning.” As it is, Kurtis was content with last year’s sports car production: exactly 18 hand-tailored, variously powered cars, which cost their owners between $3500 and $5000. Yet the line continues to form on the left. Back orders for sports cars come from as far away as South Africa and the Philippines. Only recently flamboyant used-car and television dealer “Madman Muntz” announced he’ll produce a much modified Kurtis sports car to sell for around $5000.

As one automotive old-timer commented, “Well, at last Frank is jumping on his own bandwagon.”

Workadays, which includes Saturdays and Sundays, except during May when he’s at Indianapolis, find Kurtis designing and building race cars. Some years ago he decided he needed relaxation–so sports cars became his hobby. For vacations, he putters with hotrods. But to Kurtis, the ultimate in relaxation is to gun his sports car 250 straight miles across the Mojave for some Colorado River black bass fishing. He tries desperately, though seldom successfully, to keep the car below 90. Local traffic cops call these desert crossings “harassing tactics.”

“I’m really being considerate,” laughs Kurtis, “the car will do 140 m.p.h. as easily as 90.” Until Kurtis, American racing car design had been napping over the drawing board. European cars occasionally invaded U.S. tracks. When they did, they were the cars to beat.

There were alibis aplenty for this chronic marking of time. Some from afar, with misty and critical eye, compared American tracks to European road racing and declared that tracks were death to American racing. They said, for instance, that while European cars were constantly being revamped for speed–with no ceiling in sight–U.S. tracks were designed with built-in top speeds. On American tracks, straightaways were few and close between–so short that about 2/3rds of the race was spent broadsiding through the curves. European races were won on the straightaways; U.S. races on the curves.

Believing that each U.S. track had a set maximum speed, American car designers harped on endurance. Why design for speed, they said, when you can go just so fast on our tracks and that’s all. Meanwhile, Europeans were emphasizing acceleration on the straightaways. European cars generally pulled away from the Americans like jet fighters from a bi-winged crop duster.

The road races at Roosevelt Raceway in 1936-37 were tests of these opposing schools of design. The European cars ran circles around the Americans and when they tired of that, they made semi-circles. Defeatism had stealthfully infiltrated behind American design lines. Then in 1940, when Kurtis was a brash newcomer to big car racing, he exploded a home-made bomb by declaring, “There isn’t a track in the U.S. where maximum speeds have ever been attained.” And furthermore, he insisted, U.S. racing design had taken a forty years’ Rip Van Winkle.

There were facts and figures aplenty on Kurtis’ side. In big car racing, the Mercedes, Maserati, Alfa Romeo and Auto-Union Racers burned up American tracks. Year after year higher speeds won the 500-mile classic. Did that prove there was a “top” speed for American tracks?

Last year, for instance, the average qualifying time for all cars at Indianapolis was 131.045 m.p.h. The year before it had been 128.361. A 2 1/2 mile an hour gain and steadily climbing! When Kurtis shoved his lanky frame onto the post-war scene, American racing already had its most powerful engine, the Offenhauser. “But what’s the use of a lot of horsepower when you’re dragging a wooden plow?” he asked. To answer himself, he built his first post-war midget, borrowing some aircraft ideas. He gave it a light, rigid, tubular-trussed racing frame and torsion bar suspended wheels. That was in 1946 when Kurtis was already legend in midget car design.

Immediately, from backyard shop and from the tracks came hoots. Kurtis had climbed way out on the design limb. For Kurtis had approached the problem standing on his head. He built a rigid, tubular trussed frame–welded and heavily reinforced to take engine vibration.

Then he suspended the wheels from torsion bars–which in effect gave each wheel knee-action. Torsion bars had come from European tracks. Essentially they were steel rods which actually twisted and contracted to take up shock. Not only did the car handle easier, but more tire surface stayed on the track for greater power-transfer. Kurtis was the first to shock-mount the Offy engine on rubber–easing driver-fatigue.

To get the same effect Kurtis achieved through design, race car mechanics had actually loosened frame bolts just before a race to give their cars elasticity! Until Kurtis Kraft cars appeared at tracks, it was the driver who did most of the shock absorbing. Drivers felt like pebbles in a gourd somebody shook up for 100 miles. Kurtis didn’t arrive at his design by way of textbooks–although he shuns them less today then in his teens. Instead, he spent long days and longer nights watching races. Usually his eyes never strayed far from the wheels. He noted how rigidly supported wheels hopped off the track, wasting power. How drivers strained through the turns.

“If a car doesn’t handle smoothly, a driver can’t get maximum speed,” he reasoned. Speed follows safety. And easy handling precedes them both. A couple of years ago when driver Duke Densmore careened off the track, looped over the wall and took up company with a palm tree during qualifying for an AAA 100-mile sprint at Del Mar, California, drivers pointed to the Kurtis frame.

A lot of opinions were modified that day. The Duke was carried away from that wreck only slightly injured, thanks to the sturdy tubular frame which, while bruised, wasn’t badly bent. Had the frame been made of channel iron, as previously, racing could have had another casualty. Two days later, the Duke smacked another tree, this time while on a state highway driving his own car home from a party. Bandaged and bruised, he declared he felt a whole lot safer in a Kurtis car.

Kurtis’ following among that fanatic, and often times pecuniarily loaded tribe of sports car fans is legendary. It’s a crowd that thinks $10,000 a modest price for a car. Nowadays Kurtis seldom relieves them of more than $5000 of their money at a time. Kurtis surveyed the sports car picture and asked himself a question: “Why?” Why were all the top sports cars of European design? Cars like the Jaguar, M.G., and Allard had no American competition. In fact, until Kurtis built the Kurtis-Kraft just after the war, not one U.S. builder had ventured into the field production-wise for 20 years.

The first sports car he ever built–forerunner of the Kurtis-Kraft–was the biggest package of automotive “firsts” ever concocted from expensive junk. It’s a chapter some automotive experts dispute–but when Frank built it in 1928, he was an unknown kid of 20. He’s got the photos to prove it, and a few oldtime mechanics remember the car. It had among other “firsts” concealed running boards; fender skirts; a streamlined body; a convenient glove compartment; and instruments huddled conveniently in front of the driver. It was the first automobile to conceal the spare tire in the rear compartment. A powerful engine goosed it along at almost 100 m.p.h.

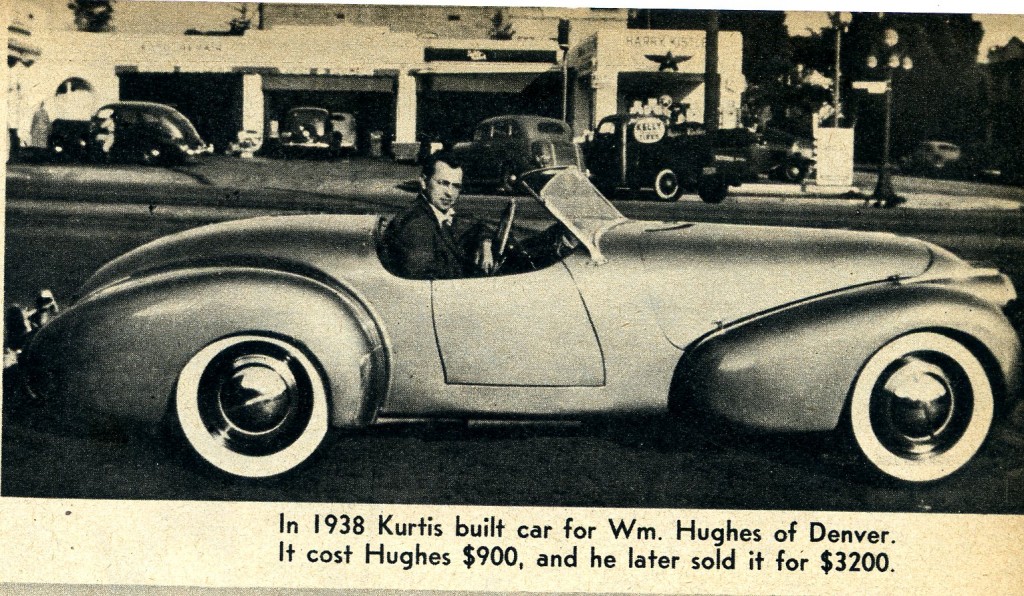

In 1938, Kurtis designed and built a sports car for wealthy cattleman Bill Hughes of Denver. It was a design 10 years ahead of any sports car of that day, and Kurtis built it for a paltry $900.00. Hughes later sold it for $3200 to a Hollywood director. Then a couple of years ago–when the car was pushing 10 and due for retirement–a wealthy cameraman barged into the director’s office.

“I’ve got to have that Kurtis car,” he said harriedly. “My wife’s in love with it, and I’m in love with my wife.” But the director said he wouldn’t sell–not for any amount. Not even when the car was involved in a romantic triangle. “I’ll give you $5000 for it,” the cameraman persisted. Still no sale. The price went up to $6000–$7000–then $8000. Still the producer shook his head. Finally, the cameraman scrawled out a check for $8000, threw it on the producer’s desk, and stomped out of the office, declaring, “I want that pink ownership slip by tomorrow.”

The director finally relented, and sold the car!

Now comes the sequel. A few weeks ago, the Hollywoodian and his automotively addicted wife were packing up for Tangier–where they expect to live. As the gal climbed from behind the car’s wheel for the last time, she wept. “I can’t leave ‘Drool’ behind,” she sobbed. She’d named the car “Drool” because “that’s what I do over it.” So now the car which Kurtis built 12 years ago for $900 is on its way to Tangier–via Marseilles. The freight bill alone was $1100–two hundred bucks more than it cost Kurtis to build.

Recently, when an investment broker suggested to a top-flight midget driver that he sink his dough in some gilt-edged securities, the broker was rocked back on his financial heels when the guy retorted: “Hell, you can’t guarantee me more than 12% return a year. If I buy a Kurtis midget maybe I can make 100% the first week!” Of the 550 midget racers which Kurtis has turned out since the war’s end for around $5000, a score have paid for themselves the first week. In 1947 he made a rush delivery of a midget chassis to an eastern owner–for $4800.

A week later the car had won $9000 in prize money and traded hands at Indianapolis for $12000. The owner promptly wired for another car. To him, as to many another, a Kurtis car is a gilt-edged security with an Offy engine and the prettiest shape this side of Marie Wilson. Remembering back now, Kurtis is a little dumb-founded when sports writers dub him the “Henry Ford of racing.” But he’d rather have his name festooned with automotive lingo than with the kind of stuff a Hollywood producer handed out while considering Kurtis for a part in MGM’s “To Please A Lady,” which stars Clark Gable as a tough race driver.

“I don’t want you to out-Gable Gable,” the producer warned. There’s a striking resemblance between the two. Kurtis, meeting Gable a few months ago, was a little self-conscious–until he discovered that Gable owns a Jaguar and that MGM had bought a Kurtis car to co-star in the picture. After that, they settled down to the lingo Kurtis knows best.

Some of racing’s biggest names have spent the greater part of their careers in Kurtis cars–first midgets, then in big cars. Typical are Johnny Parsons, Sam Hanks, and Duke Nalon. Every year some lucky moppet sits down with Frank to go over Soap-Box derby plans. It’s as if a jet designer helped a kid with his box kite, but Frank gets a kick out of it. A couple of years ago when he was asked to design a motorized midget car for the Junior Midgets of America. Kurtis amazed his client by arriving at San Marino, Calif., equipped with only a crayon and a roll of wrapping paper.

He tacked the paper to a wall, then asked a kid of average size to sit in front of it on a low stool. Then and there, Kurtis designed a car around his live model, sketching in the details on the wrapping paper. The midget car was a giant success.

The late, great Rex Mays catapulted Kurtis into the midget racing game. Kurtis and Mays were standing in the infield at Los Angeles’ Gilmore stadium back in 1939, watching the midgets shriek around the oval. “I don’t like the way my car handles,” Mays confided to Kurtis. “It’s like putty on the turns, but it’s the best they build today.” Kurtis, who had built some midgets since 1936, and had his revolutionary midget on the drawing board, snapped back: “I can build a better car then any of these.” Inspired, he and Mays took hasty leave of the track and spent the rest of the night over Kurtis’ drawing board.

Kurtis showed Mays how lowering the center of gravity would stifle a car’s urge to lift off the track; how switching from old arched Model T spring suspension to a flat spring would smooth out the ride, give the car trackability; how to balance a car to transfer the weight from wheel to wheel.

One trick Kurtis employed was to apply wedges under the springs to load the left side of the car, compensating centrifugal loads on the corners. “It’ll cut down your fatigue and transfer maximum power to the track” Kurtis explained. A few weeks later Mays had his new midget–for a piffling $550–and overnight it became the leader that paced the track. “It handles like a dream on the turns,” Mays’ driver enthused after beating the field his first day out. He’d won on the corners–gunning it when the other drivers stomped on the brakes.

Summary:

Quite a lot of Kurtis history to digest at once, but coming from ’52, it’s a rare insight into the early years of his success.

Hope you enjoyed the story, and until next time…

Glass on gang…

Geoff

——————————————————————-

Click on the Images Below to View Larger Pictures

——————————————————————-

Excellent article. Thanks. You always find the good stories.