——————-

Note: This is the second part of a two part story concerning the history of Plasticar’s Marquis. Click here for the other part of this story

——————-

Hi Gang…

In the previous article about this car, the Marquis by Plasticar of Doylestown Pennsylvania, we discussed the ’53 brochure which touted the “soon-to-be” released fiberglass version of the Marquis shown in their brochure. Thanks to the effort of Marvin McFalls, Roy Smith, and the folks at the “Renault Owners Club of North America” (of which I am a member too), we now know the “rest of the story” concerning this beautifully built sports car.

Let’s take a look at the story published by their organization in “Renault News” in the Fall of 2009:

Mystery Marquis

Renault News: Fall 2009

Renault Owners Club of America

By Roy Smith

The car belonged to my father, Raymond Buckwalter; he drove it for a while, and then parked it up. I soon found out why he parked it up when I wanted to drive the car for a few months in 1958. Every time I turned the motor off and left it for a while, the car wouldn’t start again without a push. This kind of thing you remember, believe me! I always parked in the same parking lot and the attendant always saved a spot for me.

Five days a week they would push me to get it started. I guess my father figured I couldn’t go shopping unless I could find some kind person to push it a few feet, but as I was a young lady at the time, I always found some kind gentleman to give me a push. It was the battery; something was draining it.

Rather than fix it my father liked to challenge me and he would often laugh at how I managed these small challenges. Now the memory of it makes me laugh – I can just imagine me in a parking lot at my age trying to get someone to give my car a push! When I went to get it painted in the late 90s we found traces of blue, so I assumed that was the original color.

Those words from June 2009 talk of a time decades ago.

I owe several people thanks for the information and photographs that appear here, so I will do it now. From the USA, Dan Woods and his mother Mary Ann – those are her words above – and Marvin McFalls, President, Renault Owners, Club of North America.

A thank you, too, to literary friends in France: Jean-Luc Fournier and Christian Descombes. I also commend to the reader various bibliographic sources: Chappe et Gessalin by Michel Delannoy; Jean Rédélé – Monsieur Alpine by Jean-Luc Fournier; Alpine by Dominique Pascal; and Alpine Label Bleu by Christian Descombes.

Those words of introduction and the photograph above, personally from the owner, tell of a time in the 1950s and a very interesting car. The evidence uncovered suggests that this is almost certainly the original Rédélé 1953 Renault Special that was in the early weeks of January 1954 modified, tidied up, prepared and shipped to the USA for the New York Motor Show of 1954. This was the car that was used to raise interest and promote sales of a car planned to be built in the USA during 1954 to be called The Marquis.

I had read a few words about the Marquis in several places, but much it seems may have been speculation, so I decided to research the subject. Coincidentally, an Alpine Renault contact in the USA, Marvin McFalls, had been tracking down a likely car and it was he who put me on to Dan Woods, son of the owner of a car that looked remarkably like the so called Marquis.

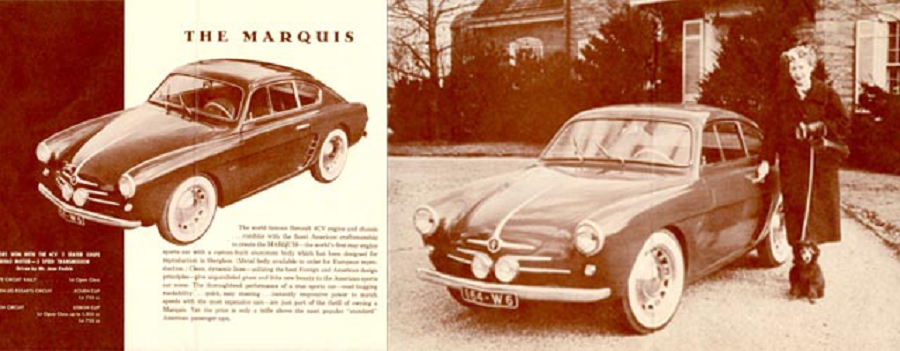

Marvin had heard about this car tucked away in a barn in Pennsylvania, USA, having been on the trail of the Marquis since 2001, when he received an original brochure featuring two cars, one called the Rogue, a sports roadster based on the Rosier Renault. The other car in the brochure was named as The Marquis and the text indicates that it was to be a replica of the Rédélé Renault Special from Allan Meyer . The company that had produced the brochure in question was PlastiCar Inc.

Marvin was sure the barn find was connected to the Marquis. He had already tracked down Todd Daniel in 2002 who was nearing the end of a 5-year restoration of the only known Rogue built in 1954. He hoped one day he might find a glass-fibre-bodied Marquis. We agreed to help each other with the research; this is the result.

Jean Rédélé, the son of a garage owner in Dieppe, had taken up rallying and had been using the ubiquitous Renault 4CV 1063cc. By the end of 1952, he had already proved a formidable competitor in many events, including the Coupe des Alpes, the Monte Carlo Rally and the Mille Miglia, in which he won his class. He entered the 1952 Le Mans 24 Hours and finished in 17th place overall; with co-driver Guy Lapchin, they covered some 2388km (1483.834 miles).

In 1953 Rédélé, along with his rally co-driver Louis Pons, again went rallying and also entered the Mille Miglia, finishing 8th in the Sports 750cc class. 13-14 June saw them in Le Mans for the 24 Hours of that year, but Rédélé and Pons failed to finish. By now, though, Jean Rédélé definitely had other things on his mind: he was dreaming of becoming a car manufacturer. The future father of the marque Alpine had in his hands a recently ordered lightweight car built on the floor pan chassis of a Renault 4CV.

Evolved in 1952 after Rédélé had met Giovanni Michelotti, a young Italian designer trained by Giovanni Farina who had worked with Serafino Allemano before setting up his own studio in 1949. Michelotti became a design sub-contractor of Allemano, Ghia and Bertone.

Jean Rédélé liked the quiet Italian and asked him to design a sports coupé on the base of the 4CV. Happy with the result, he asked him to make the car, entrusting the bodywork specialist Allemano to do the work. Rédélé was to collect the finished vehicle in Italy and drove it back to France in December 1952 at the end of a holiday he was to call a honeymoon following his marriage to Michelle Escoffier, daughter of Paris Renault dealer Charles Escoffier.

The aluminium-bodied creation on the 4CV chassis weighed just 550 kilos. It wasn’t perfect, but it had his signature: it was his first car. Under the rear engine cover, the original engine was greatly improved by the modification of mechanical parts acquired from Satecmo and a Rédélé-Pons-Claude 5-speed gearbox. He had entered it as a Renault Special in the Dieppe Rally.

Carrying No. 229, he won the event in front of a 3.4 litre Jaguar XK120 and in doing so won all the categories, as it was the car with the smallest power unit! For his second event it underwent some modifications. Visually, the front chrome work was changed, much of it being removed. He cut out a vent below the rear wing to improve cooling to the engine and on 15 July 1953 at Rouen Essarts, in front of 20,000 spectators, he won again in the 750cc class.

He repeated the feat once more at the Coupe de Lisbon on the Monsanto circuit in Portugal on 26 July, winning his class and finishing fourth overall behind three Porsche 1500s and in front of several more powerful cars.

June 30, 1953 had seen the first Chevrolet Corvette roll off the assembly line in Flint, Michigan. The concept of an all-glass-fibre production sports car had just become a reality. Glass fibre had arrived on the scene many years before: in the 1880s a glass maker from Massachusetts by the name of Edward Drummond Libbey had first discovered that glass in fibre staple silk-like format could be woven as a fabric – he even had a dress made that was exhibited at the Chicago World Fair in 1893.

Taking a giant leap to 1938, we see a gentleman by the name of Russell Slayter eventually create the product generically to be known as glass fibre and the trade mark Fibreglass was born. Our Mr Slayter had produced a continuous as opposed to a staple textile filament. The continuous filament was easily woven into a fabric which when treated with a new type of chemical resin would go off very hard.

The world at that time was on the brink of war and although this was a global disaster for populations, for science it was to drive forward many emerging creative technologies, amongst these polyester resins and the use of molded glass fibre, where it was found to have great strength when used in layered laminated format.

With the end of World War II, in France we see the pre-war-designed Renault 4CV finally see the light of day. It would become a massive success story for Renault and from early on spawned the design of several lightweight sports cars using the simple 4CV chassis as a starting point.

Men like Vernet and Pairard, Labourdette, Chappe and Gessalin would all take a look at the use of laminated polyesters. Included among these was of course the clever, opportunistic mind of the man Jean Rédélé. In the early 1950s the company Chaumarat in France had been working with the Chappe brothers to perfect a textile fabric-like glass fibre that could be impregnated with chemical resins and moulded into shapes without creating too thick a finished rigid sheet. The Chappe fabric, as it was called in France, had arrived.

Rédélé was to see this product at Chappe et Gessalin at St-Maur and at Gaillard in Paris. Raymond Gaillard had asked Maxime Berlemont, a car body stylist, to design a two-seater coupé which was made with resin and glass fibre in a format known in France as stratyl (laminated). The bodywork was moulded at Chappe et Gessalin.

During 1953 certain events had been taking place that would influence Rédélé’s next move. He heard about and eventually met a rich American industrialist who was passionate about European sports cars: Zark W Reed. Rédélé at that time had only just got his new aluminium-bodied first car fully sorted. We will never know, but perhaps a new project was on his mind production, even.

Renault had been approached by Zark Reed and on 9 December 1953 Pierre Lefaucheux, then PDG of Renault, was to take lunch with Reed in Paris. (His was one of several approaches Lefaucheux had recently received.) Reed represented PlastiCar, a company based in Doylestown in Pennsylvania, whose parent company specialized in the molding of boat hulls in glass fibre.

The company wanted to diversify its range of products by adding cars, hence the name PlastiCar. Its aims were ambitious, as they estimated that they could fit a bodywork assembly made of just seven elements and attached directly by washers and bolts to the floor pan of the Renault 4CV in fifteen minutes and produce 3000 cars a year.

The idea was that they wanted to compete with the US imports of the then popular English roadsters familiar to US soldiers who had been based in Europe and were returning home smitten by the Triumph TR2, MG and Singer. Zark W Reed was a tactician, though also perhaps a bit of a dreamer (Pierre Lefaucheux called him woolly-minded), but nothing would stop him.

Reed obtained an agreement in principle with Renault concerning the Rosier, using that design to create a car with a glass fibre body; they would call it the Rogue. But Zark was not content with this: he wanted to go further and up the ante by directly approaching another partner, enter Jean Rédélé.

Rédélé jumped at the chance of finding himself potentially in the saddle for a production deal and a shot at the American market. Shortly after his meeting with Renault, Reed visited Rédélé, who had an office in the rue Forest in Paris. Rédélé took the American out on the road in his race-winning Special and Zark Reed was immediately won over by the car and its owner. Reed decided he wanted the rights to produce the car industrially in the USA, but with a glass fibre body.

Rédélé saw the possibilities: was his dream about to become reality? Here was a company which was experienced in glass fibre and it looked like a superb opportunity to become a constructor. Rédélé didn’t have the financial wherewithal himself to produce his own cars at that point, so he decided to sell Zark Reed a manufacturing licence for the sum of $2500. But Reed stipulated in the contract that the licenser must supply him with a master to work from; that master mould would come from the Renault Special…

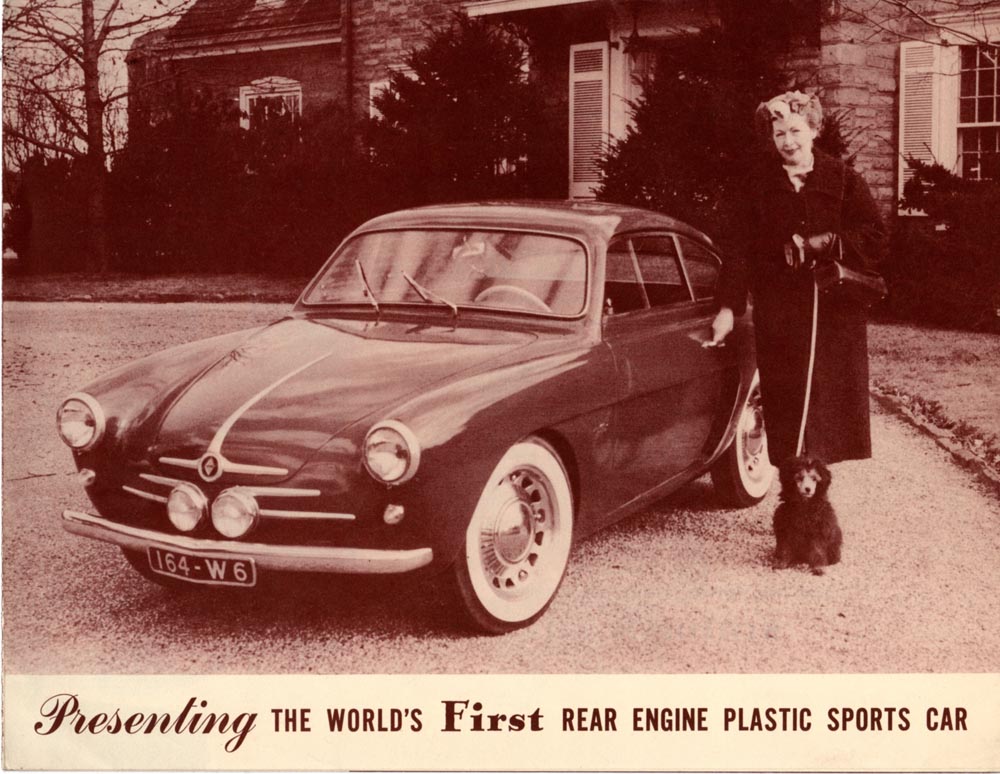

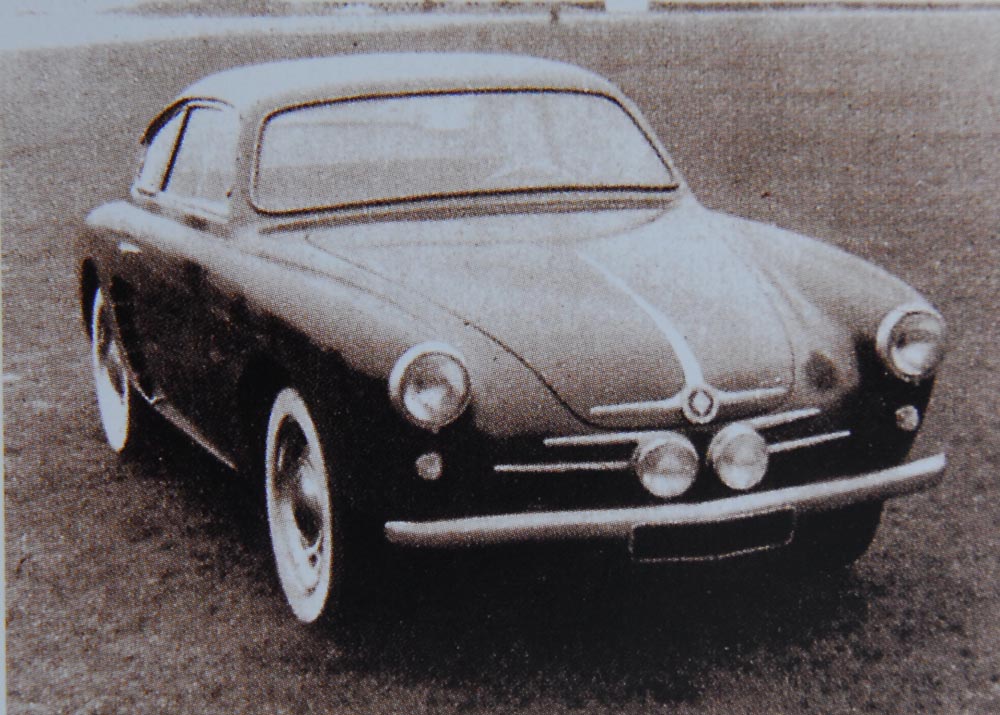

For Rédélé this was perfect. He had found the means to finance manufacture of a car linked to him – a neat financial strategy and industrial engineering solution, he thought. Jean Rédélé had the original aluminium-bodied car further modified at the front and generally tidied up; it’s likely, too, that it was repainted. The front was revised with two lights that recessed into two housings in the nose, a plain bumper was fitted and the car was sent to the New York Motor Show early in 1954.

Reed moved fast; he had PlastiCar brochures made up and published photos of the car in preparation for production, being hopeful of receiving many orders at the show. It received flattering comments from those who saw it. Zark Reed was delighted, but the dream was about to turn to a nightmare for PlastiCar Inc, Rédélé and Renault.

Unknown to all parties, Reed was being badly advised by the men he had recruited to put The Marquis, the name they had given to the proposed fibre glass car, into production. A former Chief Design Engineer at Ford who had joined PlastiCar was not up to the mark and he and his colleagues got off to a bad start. The first mold taken from a Rosier for a sports car named the Rogue had a body that was too thick and therefore too heavy.

It is suggested that they were also found to be unable to fully take on board the concept of the rear-engine design which they would have on the Marquis, planned to be a direct copy of the Rédélé Renault Special which would be made after the Rogue: the 4CV engine layout was one they were not familiar with. The enthusiastic Zark had already ordered 150 initial mechanical assembly floor pans from Renault.

On top this PlastiCar Inc, as mentioned, was finding it impossible to master the adaptation of the glass fibre process to car bodies. They were used to thickly laminated boat hulls accumulating many layers of the impregnated glass wool over long flat areas; the first Rogue body was too thick – completely useless for a lightweight sports car.

Reed suddenly found himself with a heavy, unsaleable product and he was now facing the same problem with the planned Marquis coupé, plus he had a bill for 50 million francs from Renault for the mechanical assemblies. Disaster was at hand. Jean Rédélé quickly got to hear about the problems and soon after his 750cc class victory with Louis Pons in the ’54 Mille Miglia in May with a 4CV, he went to the USA but was horrified to find that what he had heard was true and he could only confirm the fiasco to Renault during his visit.

Furious that his licensee had failed, he cancelled the agreement. It was all over. He returned to France with no money from the deal and without his first car (too expensive to ship back), anxious to recover from what one might see as a humiliation. Uncertain of the new material, Rédélé would go ahead and order a second special from Allemano but incorporating the aesthetic and mechanical modifications done on the original car for the New York show.

At this time the Escoffiers (father and son) were also working on the creation of a new car. They had thought about the new plastic, finding that at Chappe et Gessalin they were already on the case. Escoffier knew that laying down glass fibre and resin did not need the same skills as aluminium and Chappe et Gessalin had begun to acquire a good knowledge of the use of laminated fibre materials. They proposed to Charles Escoffier the production of a series of bodies. Escoffier was cautious and asked to see a first car. He was delighted and ordered 25.

Rédélé – part of the family, of course, being married to the daughter of Charles Escoffier – found that Gérard Escoffier, his new brother-in-law, was more interested in boats. Rédélé started to wonder; the new coach design of Escoffier was in fact perfect for his needs. The proposed deal to have bodies shipped from PlastiCar was not going to happen; the glass-fibre-bodied Marquis project was dead and Jean Rédélé wanted to move quickly forward.

It seems he had originally planned to take delivery of that improved second car from Allemano, based on the first one he had sent to the USA, in early 1955 with the idea perhaps being to use that as the basis of his future production model. Then a dispute arose between Escoffier and Rédélé over Jean’s idea to promote this new car by entering the Mille Miglia again in 1955, thereby creating a perceived competitor in the market to Escoffier, his own father-in-law!

In the end it was family interest and common sense that prevailed. As 1954 drew to a close, Rédélé and Escoffier joined forces in the construction of the first coach Alpine utilizing those early body shells. The cars were put together at the Escoffier Garage in Paris.

With great strategic marketing and business creativity, Jean Rédélé would now launch the Alpine company. Officially registered on 22 June 1955, the name would become world famous in the years that followed as Rédélé developed his own glass-fibre-bodied creations. The second Allemano car was supplied to Galtier and Michy who were to take a class win in the 1955 Mille Miglia with it.

As for the Marquis and PlastiCar Inc of Doylestown, Pennsylvania, USA, the only glass-fibre-bodied car they did create was the one based on the Rosier design that they called the Rogue. There appears to be no evidence that a Marquis was ever actually built and what had happened to the New York Show car remained a mystery until the previously mentioned Marvin McFalls started to investigate.

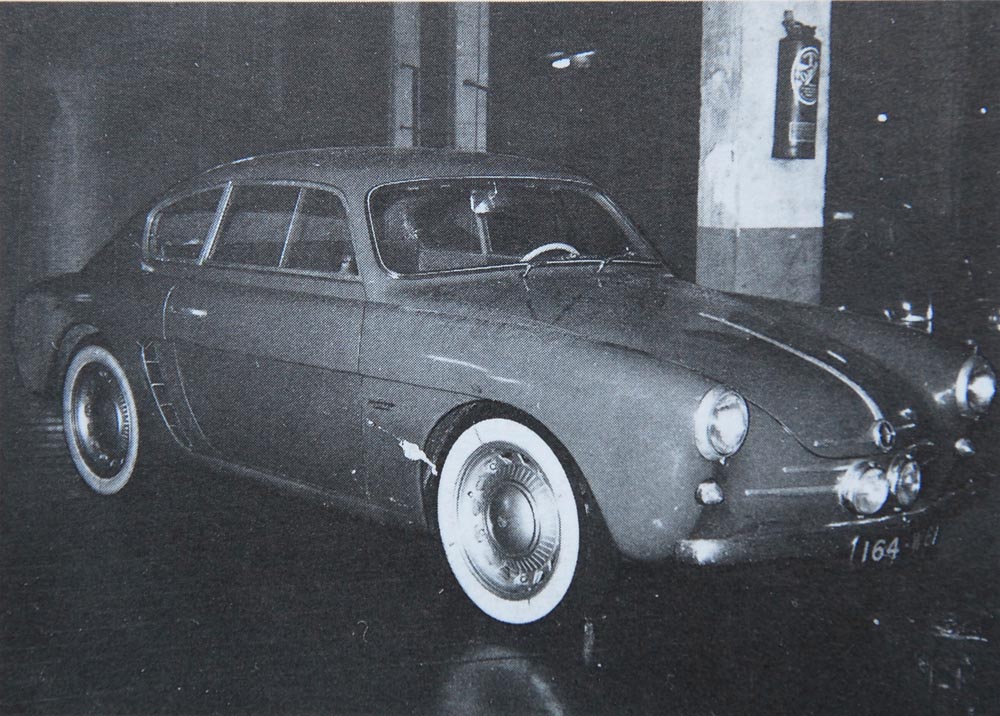

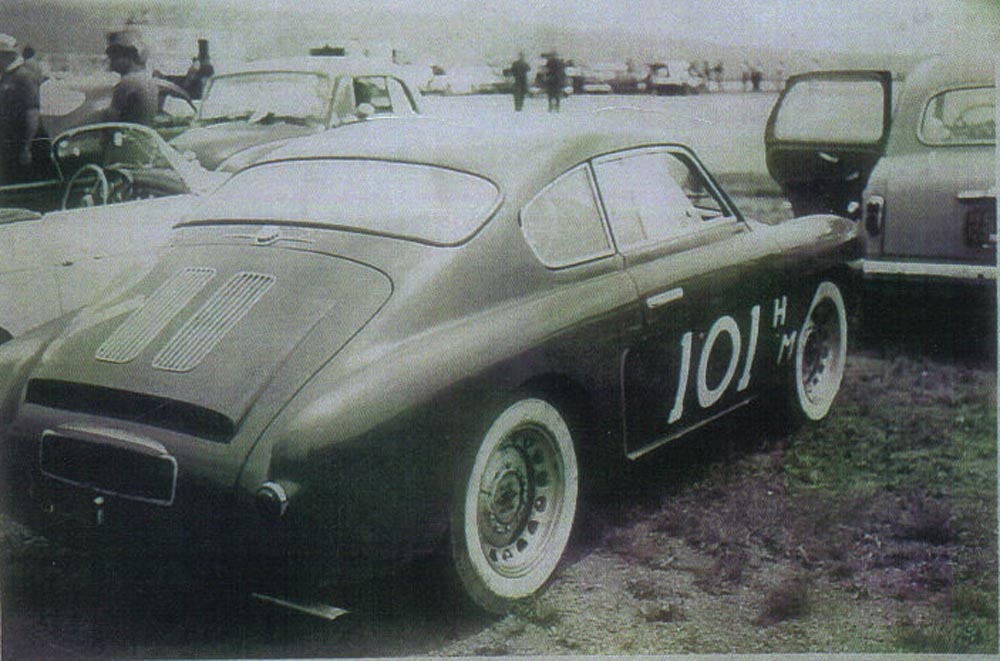

He found that the Rédélé aluminum car that was to be used as the master mold and held by Zark Reed’s PlastiCar Company had been put up for sale on a used car lot in Doylestown and purchased in 1955 by a local racer by the name of Bob Holbert. The car was seen at the Cumberland Maryland Airport race in 1956 and Marvin says the car carried the letters HM, which in that particular case apparently meant that it was entered in the 750cc class, but it was not witnessed racing.

It then disappeared.

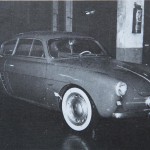

Several decades later, Jonathan Burnette, an American Renault Club member was asked about a car that a gentleman wanted to restore. He and Marvin identified it as looking like the long-lost Marquis. Eureka! Maybe? As the present owner says: My father was a keen collector of cars. He had a Lincoln dealership and had access to lots of cars.

Sometime around 1957 he was told about an interesting little coupé for sale. He bought it and used it – it was running ok until it failed to start, then I got to use it. I was told that my father bought the car somewhere in Hummelstown Pennsylvania.

It has an all-aluminum body and has been in our barn for as long as I can remember, though we can’t remember who had it painted white. In the latter part of the 1990s I had it pulled from the barn and had it repainted blue, as that was the color we found under the white and we assumed that was the original color.

A local garage man tried to get it running but there was a problem with the carburetor that was not resolvable. This is surely the missing Allemano-made, Michelotti-designed original Rédélé Renault Special, the New York Show car of 1954. The only difference is that the two central front lights are now behind the recess, not in front of it. There is also now a cover of sorts over the rear engine cover vents. Otherwise it appears to be identical.

Without further evidence, it seems that the only PlastiCar vehicle ever made was the still existing and now restored Rosier copy, the Rogue. The perceived Marquis was never finally built. Marquis or not, the exciting thing is the discovery of what must be the first Jean Rédélé-created car – the very one that won the Dieppe Rally in 1953.

The late Raymond Buckwalter couldn’t have known how important a car his purchase was to become. The good news is that his grandson has said the plan is that the all aluminum bodied vehicle will live and run again. Let us all hope so.

Summary:

What a great story by Roy Smith and thanks to Marvin McFalls, President of the Renault Club, for allowing us to reprint the story here at Forgotten Fiberglass. Two points Marvin asked me to make since 2009 when this article was published are that another Rogue and the molds have been found – which is exciting news.

And…that more history on the Marquis discussed above has also been found identifying that the car in the story above is actually the second car made in Europe – but still the earliest known prototype for an Renault Alpine that exists today.

Hope you enjoyed the story, and until next time…

Glass on gang…

Geoff

——————————————————————-

Click on the Images Below to View Larger Pictures

——————————————————————-

- The aluminum-bodied ex-New York Motor show car in the late 1990s

- First sighting for a long time – tucked away in a barn, 2007

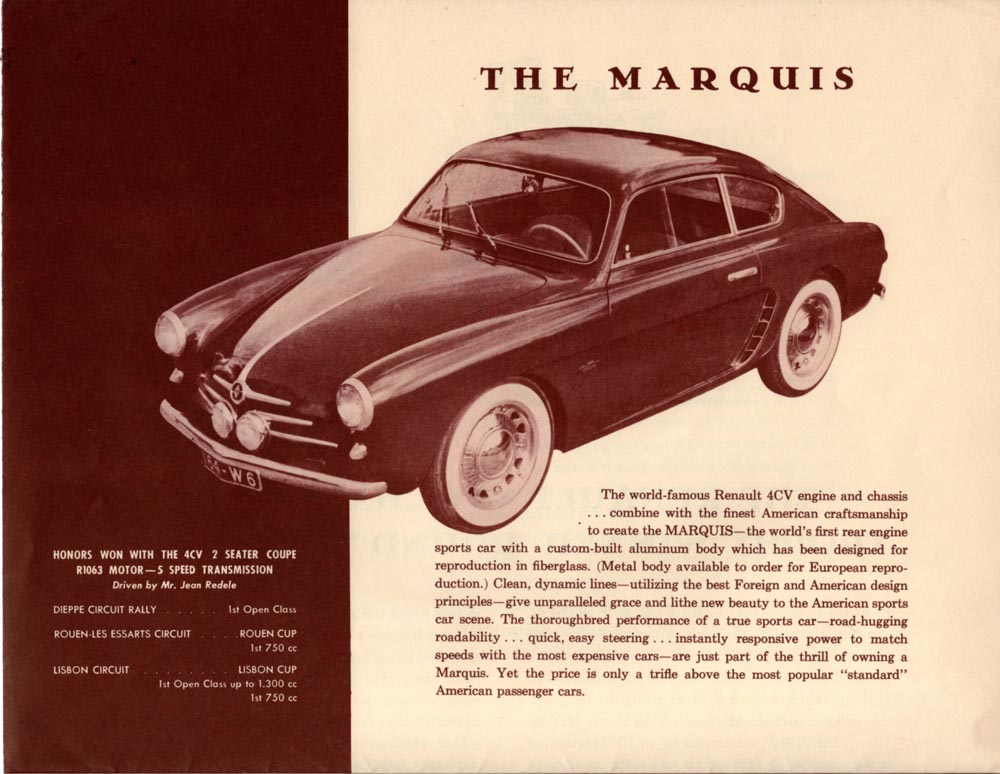

- Brochure from 1954

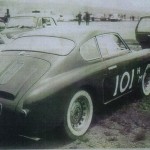

- The first Redele “Renault Special”, Rally Dieppe 1953

- Original aluminum-bodied Rosier Renault, 1953

- The Redele Special, in blue maybe – early 1954 promo for the Marquis

- Promotional photo using the first aluminum bodied car.

- The second Michelotti / Allemano car delivered in 1955

- The Redele Renault Special, 1956

- The Redele Renault Special, 1956

- This is that car

Thanks for this great story, about what I would call the start up from Alpine. Looking forward to part 3, if the story of these prototypes develop.