Hi Gang…

This is another of a multi-part story on the “Mota” electric car by Banning Electrical Products Corporation of New York. Click here to review the first part of the story on the “Mota” Glasspar Electric Car.

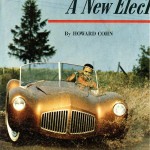

We shared the Mota brochure last time along with a great picture of Herb Shriner and the car at Shriner’s 1953 International Motor Sports Show. After the show in early 1953, an article about the Mota was published in Colliers Magazine on October 30th, 1953 – nearly 60 years ago this month.

In honor of this special anniversary we just created here at Forgotten Fiberglass, let’s take a look at what the Collier’s article had to say.

A New ElecTRICK Car

Written By Howard Cohn

“I’m going to build an electric runabout, Dad…”

“Hum,” remarked Mr. Swift musingly. “I don’t take much stock in electric autos, Tom. Gasoline seems to be the best, or perhaps steam, generated by gasoline. I’m afraid you’ll be disappointed. All the electric runabouts I ever saw, while they were very nice cars, didn’t seem to be able to go very fast or very far.”

–Tom Swift and his Electric Runabout, Victor Appleton, 1910.

Tom Swift, of course, went on to build a super runabout, despite his father’s misgivings. And in the final chapter of the book, the young inventor dramatically piloted his electric car to victory and a $3000 prize in the big race. But outside the pages of fiction, the senior Swift’s musings proved unhappily correct for thousands of people who believed around the turn of the century that electricity would be the best possible substitute for the horse in the horseless carriage.

They learned that the storage batteries which supplied power for almost all of the electric cars had serious limitations. Not only were the batteries heavy and space-consuming, but they didn’t provide enough current to threaten even the lowest speed limits. Furthermore, every few miles they had to be recharged.

Caption: Inventor Gerald Banning takes his Mota car around a curve. Only the right rear wheel is attached to the motor, but the experimental model has plenty of zip.

By 1912, there was only one electric auto on the road for every 1000 gasoline cars. Fifteen years later the electric-car market was as dead as a blown fuse. But today, a new and startlingly different electric car has made its debut on the American road – or, to be more accurate, on a limited number of highways in and around a Michigan town with the unusual name of Zilwaukee.

Mechanically, the new car bears no more resemblance to the electric runabouts of Tom Swift’s day than it does to the gas-powered automobiles that dot the parkways now. It has no complicated gears, no transmission, no drive shaft, and just a wisp of a rear axle. Yet it provides such amazing power and potential economy that despite some bugs, it could be a prototype of the car of the future.

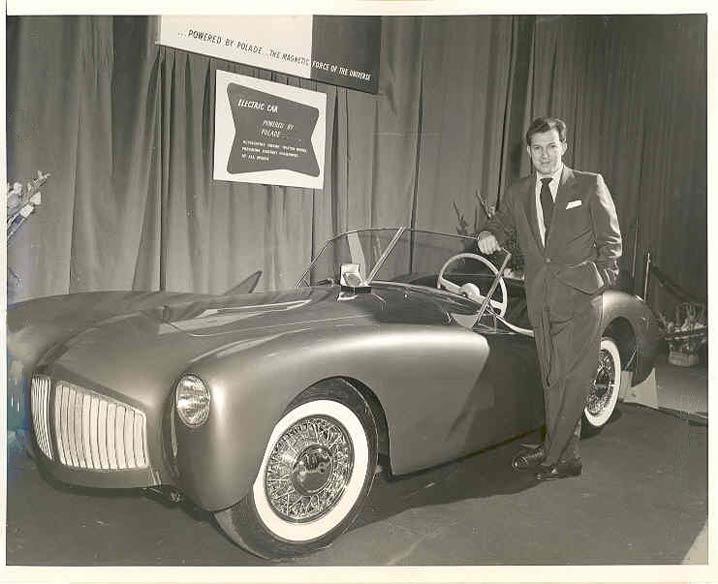

Called the Mota, the new electric automobile is a strictly experimental model that was designed and virtually hand-built by Gerald Banning, a thirty-five year old inventor and correspondence school trained electrical engineer. At the last International Motor Sports Show in New York, the first public showing of the car won Banning an award for “the most unique and advanced concept of automotive engineering in the field….”

Unlike the somber, black victorias of the past, Gerald Banning’s electric car is as dynamic-looking as a springboard. Minus its bronze fiberglass body, the Mota resembles a stripped-down, low-slung racer. With the gleaming shell on, it looks like the sleek sports cars now dotting U.S. highways in increasing numbers.

The car as it now stands is very heavy. Banning and the 17 mechanics he employees put the chassis together with whatever material they could find around his shop. It turned out to be mostly heavy steel, so that automobile weights 4500 pounds, about the same as a medium-sized truck.

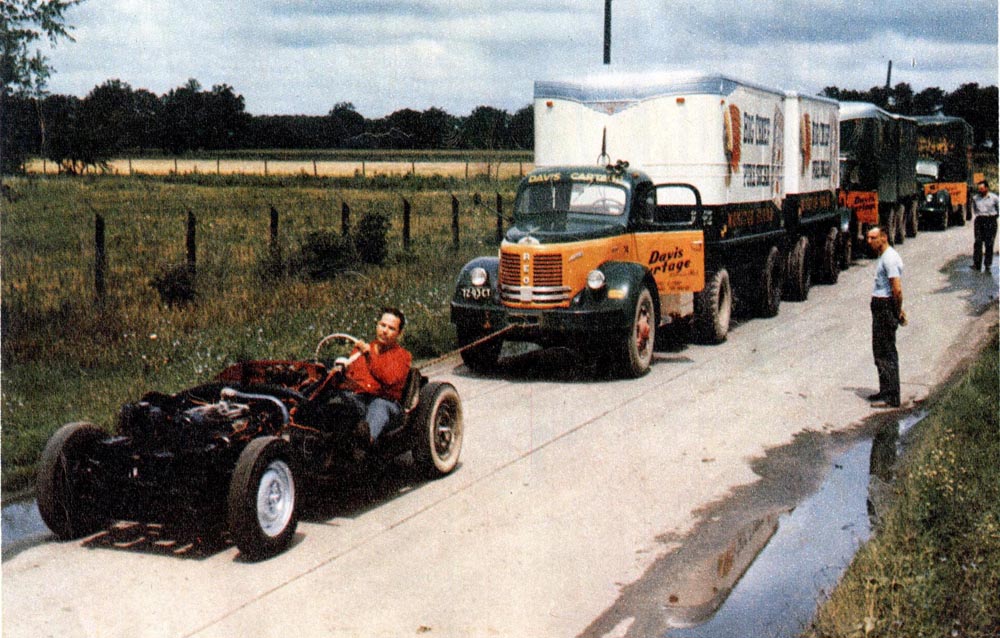

Despite this great weight, the car has no trouble hitting 60 miles an hour on the open road. Starting from a dead stop, it has towed three mammoth trailer trucks weighing a total of 32 tons. Once, for a test, Banning blocked the front wheels to keep the car from moving then gave it the gun. He literally burned the rubber off the right rear wheel, the only one connected to the motor.

How The Power Is Generated:

All that power comes from an alternating current electric motor with only 20 horsepower – compared with the 75 to 200 horsepower required for most conventional cars. Every electric motor must have a source of current; the old-time runabouts used batteries, and your household vacuum cleaner plugs into a wall socket.

But Banning wanted to dispense with the troublesome batteries, and of course he couldn’t use power-company current in a moving automobile. So he installed a generator to provide current for his motor, and a little four-cylinder gasoline engine to provide power for the generator.

The only operating cost of his car is for gasoline to work the generator – and that comes to about two gallons an hour, regardless of the car’s speed.

Why did it take so many years to find the secret of a practical electric car? The answer, Banning contends, lies in the limitations of standard electric motors. “You need a small motor that can provide a variety of speeds and has a compact, long-lasting source of current. The electric motors in general use today don’t meet these requirements. There are motors which can provide a variety of speeds, but they’re big, expensive, and complicated.

Banning began work on the problem during World War II. His goal was to produce an inexpensive alternating current motor that could operate at all speeds and would have the same horsepower output at 300 revolutions per minute as at 1800. By 1946 he was on the track of what he now calls Polade Power. Here’s how it works:

Banning started with a conventional electric motor of a type consisting of a rotor spinning at 1800 revolutions per minute inside a fixed frame. The rotor could be hooked up to any piece of machinery to make it run. Then he made one major change: he freed the previously stationary frame, permitting it to spin, too. So he had, in effect, one rotor inside another.

So long as the outside rotor, or frame, stays still the motor is like a conventional one-speed 1800 rpm machine. But suppose you spin the frame at 100 revolutions per minute in the opposite direction; then, for all practical purposes, the inside rotor slows down 100 revolutions. Spinning the outside rotor at 1500 rpm would slow the inside rotor to 300, and so on.

And that’s the secret of Banning’s new motor. By using two spinning parts, one inside the other, he is able to regulate the speed of his car. He controls the degree of spin by hydraulic pressure, adjusting the pressure with valves.

Visiting engineers have called Banning’s principle an important new development in the field of electric power. The inventor himself, an effervescent, stocky young man with a crew haircut and thin mustache,, is less modest. He thinks Polade Power is revolutionary.

Banning’s engineering background is practical, rather than theoretical. His only formal training has come from correspondence courses. But his father had an electrical shop, and the son says now that “it sems I’ve been winding electric motors since I was seven years old.”

Caption: Stripped of its gleaming cover, the auto provides a power demonstation by pulling three huge trucks.

After high school, Banning worked for his father, then spent four years knocking about the various industries in and around neighboring Saginaw. “In each job,” he says, “I got acquainted with different machines and tools. I never stayed in a job for more than seven months,, but I wasn’t fired from any of them.”

By 1938, Banning was in business for himself, rewinding electric motors and doing occasional experimental work for such major concerns as General Motors. Banning has never thought of Polade Power principally as a source of motivation for passenger automobiles. His primary interest has been in industrial applications.

Three years ago, he persuaded the Saginaw Foundries Company, which makes steel castings, to use three of his experimental electric motors on a huge ten-ton crane. This first commercial test of the Polade Power principle has been a success, although Lenwell Cline, the assistant general manager of Foundries, complains that the inventor tends to neglect a specific motor once he feels he has proved his point.

“The motors have worked well,” Cline says, “but in recent months we’ve had a little trouble with the control system. There really isn’t much wrong; if Banning would come around and give us a little maintenance once in a while, the motors would work even better.”

One reason the inventor hasn’t been around very often is that he and his men have been working into the early hours of the morning building the pilot motors which he hopes will mean riches for him – and for the 160 other stockholders who helped him organize Banning Electrical Products Corporation.

Other Firms Will Do The Selling:

The general financial plan is for Banning to design and build Polade Power motors with specific purposes in mind, then turn the sales rights over to outside companies. In return, Banning Electrical Products will get a sum of money, guaranteed royalties on future sales of the motor, and a contract to engineer – and in some cases manufacture – the motors that will be evolved from the pilot models.

The sales rights to three types of motor will stay right in Saginaw. Howard Doss, a Banning stockholder who is president of a firm which makes house trailers, already has put his money down for control of a power wheel that Banning wants to develop.

The inventor’s plan is to house a Polade Power electric motor inside a wheel, thus providing a vehicle with tremendous direct power and traction. Doss plans to adapt the wheel to farm tractors, heavy trucks and perhaps military tanks.

It was while trying to develop the power wheel that Banning got started on his electric car: the new wheel will get its electricity from a gasoline-driven generator and the inventor needed something on which to test the principle. Banning is the first to admit that his present electric car is far from a finished product.

“Ideally,” he says, “it should have one 10-horsepower electric motor mounted beside each rear wheel. But since we built it with our own money, we had to cut corners sharply. We hooked up just the one 20-horsepower motor on the right wheel because it was the only one around that we could spare.

The chassis is welded out of some old heavy steel we had around the shop, and instead of trying to cover the hydraulic pipes that regulate motor speed, we left them unconcealed. At that, the car has cost us $15,000 and 2500 man-hours to build. And we haven’t finished tinkering with it.”

Because Banning and his men are still tinkering, the Mota changes appearance almost daily. In all its versions it’s crude – in looks (under its fiberglass shell) and in operation. Banning believes he could build a Polade-powered car that would equal the record bursts of speed the old Stanley Steamers used to provide. Once it had the steam, a Stanley Steamer could accelerate from zero to 60 miles an hour in 220 feet. But with the present Mota, acceleration to that speed takes more like 2200 feet.

The reason for the delay lies in the valves that control the hydraulic pumps – and therefore the speed of the car. Banning has been unable to buy satisfactory automatic electric valves, so he uses valves that are turned by hand – the same type you have on the hose spigot in your backyard. There are six in all, and Banning says, “I’m kept so busy turning valves I feel like a gardener regulating a sprinkler system.

“But,” he adds, “in my electric car of the future there will be just one little lever on the dashboard for forward, and one for reverse. When I want to go forward, I’ll just press the proper lever and step on the gas.”

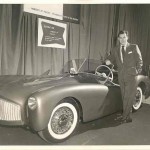

Despite his emphasis on what he hopes to do in the future, Banning is proud of the present car and its performance. Actually, part of the credit for converting the dream of a new electric car into a reality belongs to radio and television comedian Herb Shriner, a devoted automobile enthusiast. When Shriner heard early this year about Banning’s project, he insisted that the inventor exhibit the car at the International Motor Sports Show (1953) in New York, which Shriner was sponsoring.

Shriner’s Confidence Justified

The Mota was in select company. The show, which was held last April, featured such prize exhibits as a 1912 Rolls-Royce and a $29,000 Spanish Pegaso. “Not only did the electric car win Banning a prize for advanced engineering thinking,” says Shringer now, with the happy air of having spotted a winner, “but it turned out to be the most popular attraction in the show.”

Banning hasn’t yet decided what the future of his electric car will be. He’s received a few nibbles from sports-car manufacturers who want to purchase the rights to the motor, and he’s inclined to believe he will accept one of them.

“We’ve proved our principle,” he says. “Now I’d like to see a more advanced version of the Mota in limited production as a sports car.” About the only complaint Banning has at the moment is the traditional inventors’ lament that “some people just can’t see the importance of what’s been accomplished.”

Last spring, after months of work, the car finally was made ready for the trip to New York. Wire wheels were substituted for the old ones, and the gleaming fiberglass body was fitted over the scarred handmade chassis. The handful of mechanics who had spent so many long hours helping Banning put the car together joined him to look over the results.

“Boy, what a job,” said one of his men proudly. “Just think what it could do if only it had a Cadillac motor.”

Summary:

The Glasspar G2 bodied “Mota” sounds like one interesting car. And it might exist. I just found the “Banning” family this morning and hope to have more information about this special man and his fascinating car – a car that, no doubt, was ahead of its time.

Hope you enjoyed the story, and until next time…

Glass on gang…

Geoff

——————————————————————-

Click on the Images Below to View Larger Pictures

——————————————————————-

- Caption: Stripped of its gleaming cover, the auto provides a power demonstation by pulling three huge trucks.

- Caption: Inventor Gerald Banning takes his Mota car around a curve. Only the right rear wheel is attached to the motor, but the experimental model has plenty of zip.

- Shown Here Is Herb Shriner at the 1953 International Motor Sports Show Next To The Mota.

I was there when the car was built and work on it. Along with orther project that Gerald

built. There was orther things that was turn out at the shop in Zilwaukee, Michigan.

Hi Ben. I know Diane Banning (Fischer.) She is Gerald’s daughter. We had lengthy discussions about the Mota car and her Father. This is so interesting. The family has no records of the car whatsoever. Do you know how the whole thing worked? Banning was a genius. He even had correspondence with Albert Einstein in his work. I was trying to help the family find information about the car, but there isn’t much out there. I grew up in Zilwaukee, and still live in Saginaw. Are you in the area still?

Gerald is my grandfathers brother, I have heard so much about the MOTO car, my father has pictures and articles stashed away.

I have the original Colliers magazine and found this story interesting. Thank you for making it possible for others to read.

I think I would have to have been there to see him pulling three trucks with only one wheel traction..Sounds a little far fetched to me..

Mel

This was real. I work with a guy who married Banning’s Daughter. The reason it works with one wheel is that he applied the power gradually with faucet handles, so there is no spinning or slipping. I have a first hand account from Banning’s Daughter that this did happen, and she also told me that the first semi tractor tried to pull the other two, but couldn’t. His car pulled all three. Pretty amazing for the 1950’s.

It is real. I know Gerald Banning’s daughter, and she remembers when it happened.

Neat story Geoff! The pic from the ’53 Motor Sports Show looks like the level of fit and finish was quite high – too bad that the underpinnings, apparently, were rude and crude. With the technology available today, perhaps controls could be simplified and this car could be a winner – just a thought.

Glenn Brummer

My coworker is married to Banning’s Daughter, and I heard the story of this car from them. I was interested, so I did some research. Banning was a mechanical genius. If his “polade power” concept could be applied today with computer controls instead of faucet handles, you would have a powerhouse of an electric vehicle that could revolutionize the trucking/transportation industry.