Hi Gang…

I like to go the extra mile – confirm beyond a reasonable doubt what we’ve heard time after time and have long accepted as fact. Too long, sometimes.

The story of postwar sports cars always starts with American GI’s seeing sports cars in Europe during World War II and taking this new found interest and passion back with them to the states. I always found that peculiar since the war ended in ’45, and cars like the Jaguar XK120 and others like it really came out in ’48 and later. Of course there were the prewar MGs, Singers, and the like, but from what I can tell there was much more “fighting” going on over there in the war years than driving sports cars around.

So….I’ve been on a quest to look for information on two issues:

* The postwar interest in sports cars

* The postwar zeal for building your own sports car, hot rod, custom car, etc.

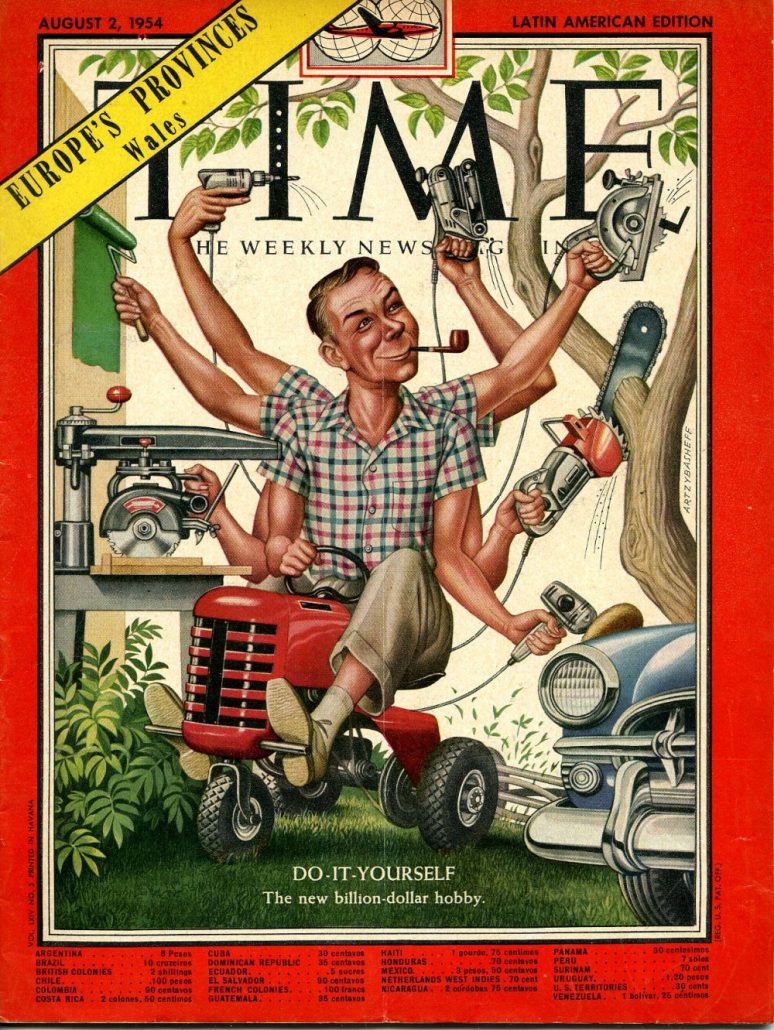

Recently, I located an article published in the August 2nd, 1954 issue of Time Magazine which gives more detail concerning what was happening, why, and when. This article was the cover story for this issue of Time Magazine, with the front page showcasing the following title:

“Do-It-Yourself. The New Billion Dollar Hobby”

Seems to me this is part of the story that I’ve NOT heard before – perfect material to use and peruse here at Forgotten Fiberglass!

As I thumbed through the article, I quickly took note of several quotes as follows:

“In Los Angeles, dozens of hot-rod clubs build their own sports cars out of junk-heap jalopies fitted with souped-up, modern engines. Some of the youngsters take surplus airplane-wing fuel tanks and turn them into 170 m.p.h. racers for speed trials on Utah’s Bonneville salt flats; others build elaborate racing cars with Fiberglas bodies and 300-h.p. power plants (often with two engines hooked together) that can do up to 240 m.p.h.”

And…

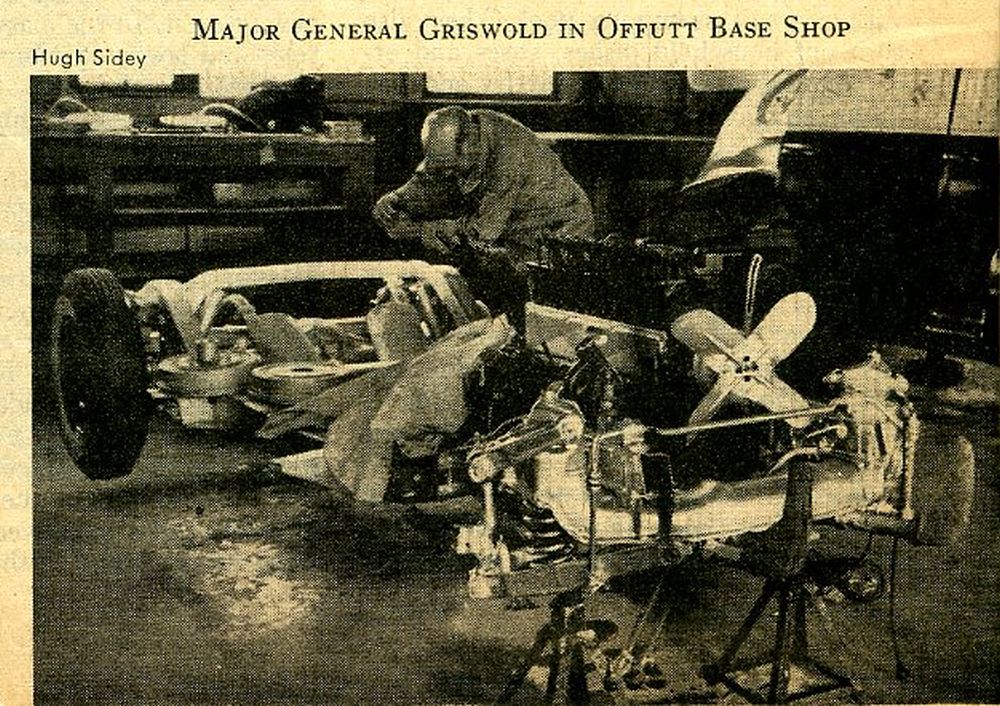

“The Strategic Air Command’s General Curtis LeMay, who is currently helping fellow airmen rebuild a private airplane, and has set up do-it-yourself workshops at SAC bases for everyone from airmen to SAC’s vice-commander, Major General Francis H. Griswold, who is reconditioning a sports car.”

And More…

“California’s Glasspar Co., which started off with $1,000 capital in 1950, is up to $585,000 annual sales selling knockdown Fiberglas sports cars for $1,466.50, without engine.”

In fact, the article also addresses where this “do-it-yourself” phenomenon began – as a byproduct of World War II where various skills and trades were taught to men and women alike. So “yes” the experience of the war years did lead to an interest in and building of products of your own hand. But what I like about this article is that it gives us a glimpse into the thinking circa 1954 of how and why the “build-it-yourself” mentality took root and raced like fire over the plains of America.

So….another piece of the puzzle is starting to take shape. Not just the American spirit and drive for something new, but the reasons for how and why this had come about. It’s a long article but worth your time, so let’s review what Time Magazine had to share about this phenomenon and its origins back in the golden era of building your own sports car.

August 2, 1954

Do-It-Yourself: The New Billion Dollar Hobby

“The Shoulder Trade”

He was a Yankee, the very character of whom is, that he can “turn his hand,” as he says, “to any thing.” —John Neal, Brother Jonathan, 1825

In New England modern-day Yankees are indeed turning their hands to anything. But so, too, are the Hoosiers of Indiana, the Sooners of Oklahoma and the Cornhuskers of Nebraska—along with Texans, Californians, New Yorkers and Iowans. North, South, East and West, Americans have joyfully taken up a new hobby: “Do-It-Yourself.”

In the postwar decade the do-it-yourself craze has become a national phenomenon. The once indispensable handyman who could fix a chair, hang a door or patch a concrete walk has been replaced by millions of amateur hobbyists who do all his work—and much more—in their spare time and find it wonderful fun. In the process they have turned do-it-yourself into the biggest of all U.S. hobbies and a booming $6 billion-a-year business. The hobbyists, who trudge out of stores with boards balanced on their shoulders, have also added a new phrase to retail jargon: “The shoulder trade.”

Cabins & Comics

In Los Angeles last week, the Pan-Pacific Auditorium held its second annual show for the shoulder trade. There were 300 exhibitors displaying everything from a build-it-yourself log cabin ($600) to assemble-it-yourself swimming pools, garage doors, gymnasiums, and gas stoves. In five days 100,000 West Coast fans paid $1.10 apiece to browse through the show and buy $1,000,000 worth of paints, power tools, plywood and plastics for their new hobby.

That was only a drop in the flood of products that goes to the shoulder trade. Last year 11 million amateur carpenters worked on 500 million sq. ft. of plywood with 25 million power tools, burned enough electricity to light a city the size of Jacksonville, Fla. for a year. Amateur decorators slapped on 75% (400 million gals.) of all the paint used in the U.S., pasted up 60% (150 million rolls) of all the wallpaper, laid 50% (500 million sq. ft.) of all the asphalt tile, enough to cover the entire state of Oregon. And while the menfolk labored mightily, 35 million U.S. women made their own clothes (using 750 million yds. of cloth), gave themselves 32 million home permanents, leafed through millions of copies of do-it-yourself magazines and books, looking for still more projects for their husbands and themselves.

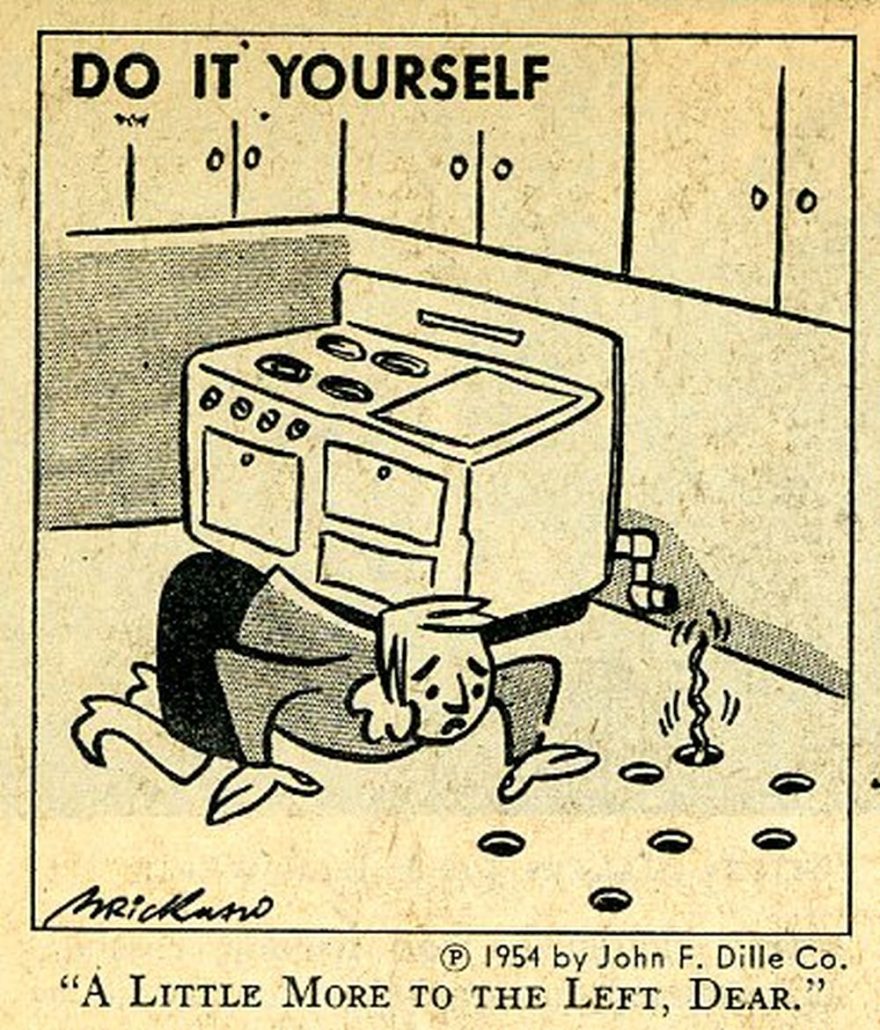

In the do-it-yourself cult are such bigwigs as U.S. Steel Vice President David Austin, who has a two-room, $5,000 woodworking workshop packed into his Pittsburgh apartment; former Secretary of State Dean Acheson, who makes his own furniture; TV and Radio Luminaries Desi Arnaz, Edgar Bergen and Fibber McGee, who spend their spare time puttering around with shelves and kitchen cabinets; Movie and Recording Stars George Montgomery, Perry Como, Dan Duryea and Jane Russell, who do their own handiwork, build boats and furniture; the Strategic Air Command’s General Curtis LeMay, who is currently helping fellow airmen rebuild a private airplane, and has set up do-it-yourself workshops at SAC bases for everyone from airmen to SAC’s vice-commander, Major General Francis H. Griswold, who is reconditioning a sports car. Recently, the hobbyists found themselves in a comic panel called Do It Yourself, now syndicated in 83 newspapers.

Cooks & Cats

In addition, there are 100 “How To” magazines, and in New York City’s public library there are 3,500 how-to books, 250 on cooking alone, both for the gourmet (Escoffier Cook Book) and the not-so-rich and not-so-particular (The Can-Opener Cookbook). Gardeners can pore over Perennials Preferred, Rockeries, Principles of Weed Control, animal lovers over such volumes as How to Tempt a Fish, How to Live with a Cat. There are dozens of books on How to Buy a House and how to make it better. There is even one on How to Make Sense.

To do-it-yourself buffs, there are few projects too difficult to try. Examples:

> In Pleasantville, N.Y., the Easi-Bilt Patterns Co. puts out nine different blueprints for do-it-yourself home builders. Since the war it has sold 250,000 plans, estimates that 70,000 of its do-it-yourself customers have managed to build their own homes.

> In Milwaukee, a Korean war flyer named Paul Poberezny formed the Experimental Aircraft Association for do-it yourself flyers to make their own airplanes. So far, the group has 600 members spread around the U.S. who have flown 500 of their creations. One man is working on a combination plane and car with a pusher propeller and folding wings; another hopes to sell a do-it-yourself small plane kit for $1,000.

>In Los Angeles, dozens of hot-rod clubs build their own sports cars out of junk-heap jalopies fitted with souped-up, modern engines. Some of the youngsters take surplus airplane-wing fuel tanks and turn them into 170 m.p.h. racers for speed trials on Utah’s Bonneville salt flats; others build elaborate racing cars with Fiberglas bodies and 300-h.p. power plants (often with two engines hooked together) that can do up to 240 m.p.h.

> In Northfield, NJ. (pop. 3,500), Mayor G. L. Infield thought bids to paint the City Hall were too high. So His Honor and 23 councilmen and citizens rolled up their sleeves, wangled free paint, and did the job themselves. Cost: $30 (for beer), a saving of $1,470.

How It Began

The great postwar hobby got much of its start from the war itself. During their service years, millions of Americans learned for the first time how to repair radios, engines and dozens of other machines. Housewives who had been punch-press operators, welders and electronics technicians found that it was no trick to fix a leaky faucet or paper a room, especially as it was hard to hire anyone to do it. Doing it herself was also less expensive, since the wages of carpenters and plumbers had jumped far higher than those of many other workers. Says one do-it-yourselfer: “A $1.25-an-hour bookkeeper is not going to pay a $3.50-an-hour carpenter very long.”

For many Americans, do-it-yourself makes possible luxuries that once existed only in their dreams. In Santa Fe, N. Mex., Joseph Wertz, a retired architect, lives handsomely on $3,000 a year by making what he wants, with the help of his wife Jean. Like many others, they have found a new source of happy companionship in doing tasks together. Working as a team, the Wertzes have built their own ultra-modern fieldstone house with a small swimming pool. They also turn out household dishes, vases and ornamental ceramics, belts, jewelry and furniture. In Hingham, Mass., Jozef Piekarski came home from World War II dreaming about a house far beyond his bankroll—a 17th century Cape Cod Colonial of shingle and red brick. Joe Piekarski has been working on his house for six years; it is still not completely finished, but it is snug, neat, and beginning to look luxurious. Its appraisal value already is $25,000. Cost to Do-It-Yourselfer Piekarski: $11,000. The difference, he says, “came out of my hide.”

Sense of Accomplishment

Economic necessity was not the only cause for the boom. Housebuilders had more time, thanks to the five-day week, longer vacations and more holidays, and they had a new interest. In the mass migration to the trees and lawns of suburbia, some 7,000,000 people got houses of their own for the first time—and immediately set to work improving them.

Furthermore, the whole character of U.S. life has been undergoing a complex change. As mass-production techniques have broken jobs into smaller and smaller parts, the average American worker has often lost sight of the end product he is helping to build; his feeling of accomplishment has been whittled away as his job has become only a tiny part of the whole production process. In the same way, the meaning of the tasks performed by white-collar employees and executives often becomes lost in the complexities of giant corporations; it is hard for them to see what they are really accomplishing. But in his home workshop, anyone from president down to file clerk can take satisfaction from the fine table, chair or cabinet taking shape under his own hands—and bulge with pride again as he shows them off to friends.

Good Medicine

The therapeutic value of do-it-yourself is hard to overestimate. One Dallas doctor, a do-it-yourself addict himself, often advises patients to “go home and start doing things themselves.” A harried executive who took up woodworking in his spare hours to ease the tension swears that it kept him from suicide. In Minneapolis an elderly dowager recently walked into a hardware store to look at power tools. “For your husband, Madam?” asked the clerk. “Good heavens, no,” said she. “I want them myself.” Her doctor had told her to take up knitting, but she thought woodworking sounded more interesting.

One successful Zion, Ill. jewelry-store owner, Wesley Ashland, cured himself of a nervous breakdown by building his own home. He got out in the woods, found a plot with a small ravine and creek, oaks, elm, hard maple and hawthorn. He drew his own design for an L-shaped ranch house, planned it so that he could save all but two of the trees. He built a bridge over the ravine with 340 bolted railroad ties, and laid a 350-ft. winding lane, bought saws, an electric drill, a jeep, and an old concrete mixer. He built a concrete and limestone house, worked through the winter in 10°-below-zero weather. Inside the four-room house all closets were cedar-lined, all screens and storm windows handmade of aluminum. He did all the plumbing, wiring and paneling himself. To him, the backbreaking work “is a relaxation.” Now, at 60, he is healthier than he has been in years.

Lilacs on the Roof

But for beginners, do-it-yourself is often a painful succession of bashed thumbs and bruised egos. In their haste to build, they often take on complicated projects for which they have to learn a dozen skills, often find themselves in tragicomic jams. One enthusiast, who decided to build two bedrooms and a bath in his attic, put his wife to work tacking insulating paper between the room partitions and outside walls of the house. An hour later, when she tried to crawl out, she found herself nailed in between inner and outer walls. In Boston a do-it-yourselfer soaked his roof shingles in a preservative mixture of kerosene and 20 gallons of scented brilliantine, which he got from an aunt who was once in the cosmetics business. It worked fine, but for days the entire neighborhood reeked of lilacs. Another do-it-yourselfer indignantly returned a can of blue paint, complaining that she could not make it bluer. “What did you use?” asked the dealer. “Why bluing, of course,” she replied.

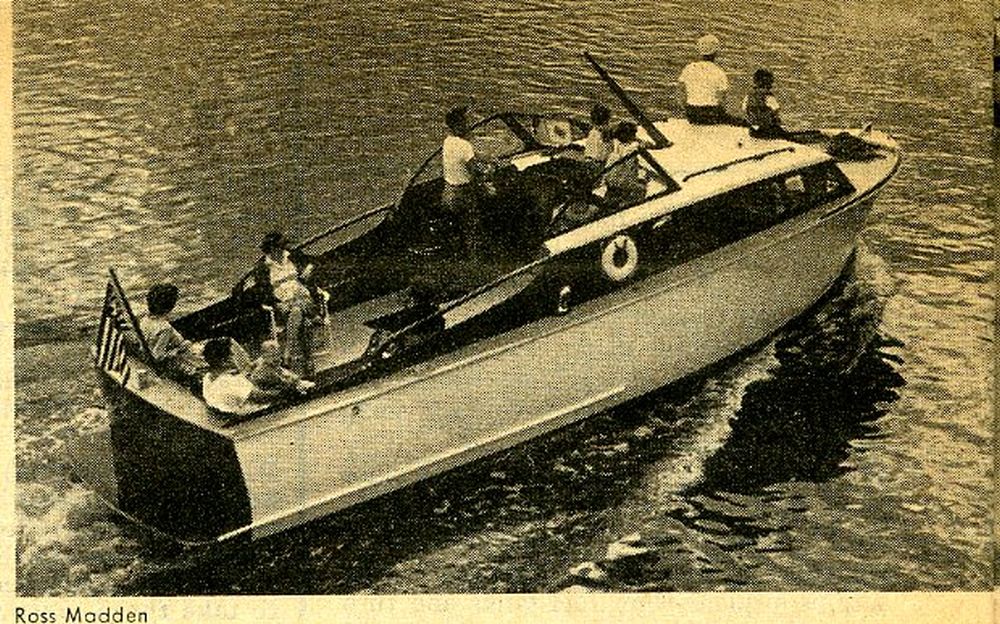

After running into such trouble, some beginners give up and call in a professional. But most do-it-yourselfers are a hardy, bulldog breed, and constantly astound friends by their ability to overcome all obstacles. Prime examples are Sherman Bushnell Jr. and Charles Parke of Seattle. Bushnell is an $8,000-a-year sales manager for a local air-conditioning firm; Parke makes $5,000 as a grocery-chain accounting-machine supervisor. They set out to build a boat — a 30-ft. cabin cruiser that would do 15 knots and would normally cost $15,000 or more.

For $50 Bushnell and Parke bought a yellow, 16-ft.-by-32-ft. surplus tent, paid $49 for a set of boat plans, and got ready to work in Bushnell’s backyard. The neighbors complained that the tent was unsightly, asked the boatbuilders to move. Undaunted, Parke and Bushnell started again in a spare room in a boatyard on the shores of Lake Union. Working three nights a week for nine months, they had completed the frame before they made a shattering discovery. Though thousands of jokes have been written about it, the two boatbuilders had made the classic mistake: the boat was too big to be taken out of the door. In dismay, they dismantled the frame, carted the pieces to a leaky shack near by which they rented for $10 a month, and started all over again.

The Never Neverland

For months they worked. Says Bushnell: “The boat was driving us nuts.” Their wives got annoyed, then downright angry. Toward the end, the two were forced to spend every free hour at the yard, cutting, drilling, measuring, gluing and installing a 215-h.p. V-8 engine. They experimented with a new plastic paint, had to paint the hull three times before they found a mixture that went on smoothly without bubbles; the first four coats of varnish on the cabin peeled off like sunburned skin; there was even one heart-stopping moment when a fire broke out in the shack. By the time their Neverland finally reached the water, the two had spent $6,000 and three years on their idea. Parke was dead tired: Bushnell had an ulcer from the strain. (He still managed to work hard enough at his regular job to become a vice president.)

But the two boatbuilders were happy: they could pile their families aboard and spend happy weekends cruising up and down Puget Sound. Then, one day, the Neverland passed a lovely, wooded point jutting out into the Sound. Bushnell had a great idea: Why not build a summer cottage and a dock? Last week Bushnell was drawing plans for a one-room summer cottage and felling madrona evergreens to clear the ground. When it is finished, he plans to build a new eight-room house for his family.

Applejack to Zymurgy. Actually, the fact that millions find joy in building is nothing new. Men have puttered around since the dawn of time, constantly trying to learn new skills, gobbling up expert knowledge on everything from applejack to zymurgy. And Americans, more than any other people, have always been a nation of how-toers, of putterers, tinkerers and inventors. Philadelphia’s Ben Franklin wrote dozens of pamphlets on how to do things, from The Way to Wealth to Advice to a Young Man on the Choice of a Mistress. Thomas Jefferson spent hours figuring out such devices as a revolving chair, an automatic door opener, a dumbwaiter to bring wine from the cellar.

Boston’s earliest merchants sold knockdown chairs, casks and tables, to be assembled at home. In the 1880s a U.S. paint firm put out tiny pots of black paint so that proper ladies could spruce up their Sunday straw hats. By the turn of the century, Sears, Roebuck catalogues already offered such do-it-yourself items as plumbing and water systems, bathroom fixtures, all sorts of floor covering, paints, handymen’s tools and supplies to Americans who either liked or had to do things themselves.

“It Was Easy”

Those who have never been bitten by the do-it-yourself bug wonder how sane and sensible people get that way. For example, Sid Bernstein, 35, came back to Los Angeles from serving in the Air Force in India in World War II determined to spend every free hour lounging in his backyard. He managed to do so for 2½ years. “I could look across the street and see a poor slob mowing his lawn, carrying ladders into his house and unloading a lot of junk from his car,” recalls Bernstein. “I felt sorry for the guy, honestly. I wondered why he was knocking himself out on his day off.”

But one fateful day Lounger Bernstein was persuaded by his wife to paper a wall. “It was easy,” says he. “They make wallpaper with glue on the back, and all you do is dip the stuff in water and roll it on.” Bernstein soon bought himself a $12.75 home-carpentry set and nailed up a shelf. “Did a good job, too.” In quick order, he reversed a bothersome living-room door, made a plywood table for his son’s electric-train set, laid a tile floor in the bathroom. “Great stuff—it’s got suction cups on the bottom—no trouble laying it down.” Last week ex-Lounger Bernstein was busy building a brick walk for his backyard, a wall bookcase, and planning a handsome new cabinet for the hi-fi set he had just bought.

Coffee & Clinics

Hardware merchants have learned to make it easy for men like Bernstein to wander in for a gimlet (25¢) and then persuade themselves that what they really need is a power drill ($25). Manhattan’s Patterson Bros., which has been in business since 1848 and used to supply machine shops and small industries, now sells 95% of its products to the shoulder trade. Customers can look over 60,600 items, including ten different types of paints, varnishes and lacquers in 150 colors, shelf upon shelf of nuts, bolts, screws, doorknobs and window catches, all arranged in neat bins so the do-it-yourselfer can serve himself. Along one wall there is an array of 50 power tools that clerks demonstrate, cutting boards and drilling holes for customers to show them exactly how to do it.

Seattle’s McVicar Hardware Co. goes even further. Each Friday night the store clears its counters and holds a “do-it-yourself clinic” for 100 people on such subjects as gardening and interior decorating, with a manufacturer’s representative on hand to lecture. Owner McVicar has set up a free coffee dispenser so that customers can help themselves while making up their minds on what to buy. “The coffee stimulates their brains,” says Mc Vicar. “There isn’t any place to set a cup down, so they just go round and round, getting warmer and more receptive.”

Under the Wing

Many a company now gives courses in plumbing, upholstering, how to make furniture, screens and storm windows, how to paint and lay tiles. Georgia Tech has a twice-weekly course for 23 doctors, businessmen and housewives on painting, wallpapering and carpentry. A dealer for Hachmeister, Inc., which makes floor coverings, has even gone so far as to advertise: “We guarantee your work.”

This year U.S. industry will put out millions of do-it-yourself kits, print up plans for hundreds of thousands more projects. Milwaukee has a Rentit store that will rent out a big power saw ($35 a week) or a small electric drill ($10 a week). California’s Glasspar Co., which started off with $1,000 capital in 1950, is up to $585,000 annual sales selling knockdown Fiberglas sports cars for $1,466.50, without engine. Michigan’s Chris-Craft Corp. has 21 different do-it-yourself boat kits ranging from a $49 pram to a 21-ft., $814 express cruiser, now does 25% of its business in the do-it-yourself market.

Other companies are hurrying into the market with build-it-yourself tractors ($99 v. up to $250 readymade), knockdown easy chairs, prefabricated doghouses, six-power binoculars, porch gliders, greenhouses, even install-it-yourself oil burners and bathtubs. Chicago’s Spiegel Inc.. the No. 3 U.S. mail-order house, has 4,000 do-it-yourself products.

Rolling Revolution

For homeowners who once had to muddle along with tools and materials designed for professionals, industry has developed a vast new array of simpler, better products to make hard jobs easy. The paint roller was invented —some even with a hollow center to hold the paint—and revolutionized the paint industry. This year alone, U.S. hardware stores will sell a total of 8,000,000 paint rollers, and professional painters, who once hooted at the gadget, are now using it themselves.

To replace the old, smelly, slow-drying, oil-base paints, manufacturers brought out new lines. Such firms as Sherwin-Williams Co. and Glidden Co. developed latex-base paints that spread on handily, dry in one hour, are practically odorless. For outside jobs, compressed-air spray guns were designed for home use. For small inside jobs, paint was put in pressure cans; it can be applied by merely pressing a button.

The old, expensive ceramic tile for bathrooms and kitchens rapidly gave way to new tiles of rubber, asphalt, cork and a dozen different plastics, most of which can be easily laid. Tough, easy-to-install plastic laminates were perfected for kitchen counters; cheap, rustproof plastic screening, unbreakable transparent plastic slabs for shower baths, new lines of Fiberglas panels for sliding-wall partitions were developed. Such firms as United Wallpaper, R. B. Birge Co., and a dozen others, brought out pre-trimmed and packaged wallpaper, plastic-coated paper that washes easily, paper with adhesive already on the back so that all the homeowner has to do is wet it and slide it into place.“One Medium-Sized Board”

Lumber companies started putting out new sizes and shapes of wood ideal for the do-it-yourself market. They no longer laugh at the request for “one medium-sized board.” U.S. Plywood, biggest in the U.S., introduced panels 16 in. wide instead of the usual bulky 48 in., developed easily handled clamps to join them together. Today, U.S. Plywood estimates that 15% of its sales (1953 total: $124 million) and 10% of the industry’s total 5 billion sq. ft. yearly business is do-it-yourself, a 160% jump since 1946.

Big rubber companies, e.g., Firestone, U.S. Rubber, Goodrich, have all boosted do-it-yourself with new foam-rubber products to help amateur furniture makers upholster their own chairs, make their own pillows, back rests and car seats. The U.S. chemical industry has provided canned plaster to repair cracks and holes, easily-nailed-up plasterboard for bigger jobs. U.S. Gypsum has a new form of its Sheetrock wall panels that look like plywood. There is a whole new family of do-it-yourself aluminum products that can be cut with kitchen shears, used to make car grilles, wheelbarrows, aquariums, wastebaskets, porch screens. Reynolds Metals last year brought out a few types of rods, sheets, tubes, bars and strips, and had them selling in 10,000 stores in the first six months.

The hobbyists have bought the new products so fast that industry is hard pressed to keep pace with demand. Almost anything new catches on instantly. Three months ago, Denver’s Rocky Mountain News started a do-it-yourself column, In one of its first articles it explained how to build an aluminum carport. By noon the next day, the News switchboard had received 200 calls; seven local firms immediately went into the business with carport kits, and so far have sold 300.

The Toolmakers

In the fast-growing market, the fastest-growing business of all is in the basic machines for the do-it-yourself workshop. Before the war, the power-tool industry rarely topped $25 million in sales; now it is a $200 million business, with a 25% increase predicted for 1954, and its products are America’s most popular gadgets. Old companies in the field have suddenly come to life, dozens of new ones have popped up. Such firms as the Rockwell Mfg. Co., DeWalt Inc. and Black & Decker Mfg. Co. have brought out whole lines of better, easier-to-use tools. Black & Decker alone has 150 models, now does a $35,648,000 business annually v. $5,346,000 in 1939. Other firms, such as Skil Corp., Shopmaster, Magma Engineering Co. (TIME, March 29), have brought out portable and stationary power tools to do half a dozen different jobs. Magma Engineering’s versatile Shopsmith tool is a complete home workshop, with drill, lathe, saw and sander all rolled into one. Price: $269.50. But the real tinkerer who plans to do extensive woodworking likes to buy tools to perform each task separately and he generally has enough to outfit a small factory.

The Compleat Handyman

In his home workshop, the compleat handyman usually starts out buying a little $25 utility drill to act as a portable sander, buffer and saw. If he wants to make furniture, he discovers he needs a bigger, stationary tool for ripsawing heavy pieces of wood, buys himself an arbor saw for $150. Next he wants a jointer for cutting precise corners, which costs him $130. Then he wants something to drill deep, accurate holes, and so buys a drill press for $100. As he graduates to fancier work, and starts putting intricate filigrees in his woodwork, he needs a jig saw, and that costs $65. The heavy curved lines on his masterpieces now call for a band saw at $250. If his furniture is to have legs, he must buy a lathe for $200 to turn them. And if he really wants to turn out professional work (as he usually does), he looks around for a shaper to groove and plane it precisely. That costs another $250.

To this the do-it-yourself addict also adds a paint spray gun with an attached air compressor for $60, an exhaust fan to carry off the fumes for $20, plus a $200 collection of chisels, wrenches, hammers, screw drivers, vises and pliers. For outdoor work he buys a $125 power lawn mower, a $35 hedge trimmer, a $115 chain saw for work on his trees, a $250 tractor to plow his garden and shovel snow from his driveway. By the time he is finished, he has as much as $2,000 invested in his new hobby, and he can build anything from a toothbrush rack to a ten-room house, and landscape the land.

What Next?

Has the do-it-yourself boom reached its peak? No one thinks so —least of all the do-it-yourselfers. As their skills increase, they see themselves tackling bigger and bigger projects. The man who has put together an 8-ft. pram begins to leaf through plans for an 18-ft. outboard cruiser. The woman who has restuffed and recovered an old chair begins to wonder if she could not make a set of furniture for the dining room. Sales to the shoulder trade are climbing so fast that by 1960 the estimates are that they will be well over $10 billion.

Conceivably, then, millions of Americans will live in the happy, independent state of James W. Lowry, 45, of Cleveland, purchasing agent for Republic Steel Corp. Over the years, he has built his daughter a wood-paneled game room, installed a new furnace in his home, made Venetian blinds for all the windows, laid a concrete drive, screened in the front porch, made a suite of bedroom furniture and slipcovers for chairs, built a snowplow, and rigged a darkroom for his other hobby, photography. Says Lowry, in the independent voice of all his breed: “I don’t believe I’d know a plumber, electrician or carpenter if I saw one. I haven’t hired one for years.”

Summary:

A long article indeed, but one that I hope you found worth your time. It gives us insight into the times from the perspective of 1954 – exactly what we’re looking for to describe why these cars were being built from scratch in the 1950s.

Hope you enjoyed the story, and until next time…

Glass on gang…

Geoff

——————————————————————-

Click on the Images Below to View Larger Pictures

——————————————————————-

The “DO IT YOURSELF” generation is now 50 and older. I wish that today’s youth had this attitude. But they are lost in that cyber world of i pods and social networks.I build my own car bodies and folks think I am some great artist, but i am just a guy that did not have a lot of money so I had to make my own stuff, like everyone of my generation. Just compare a popular machanic magazine from the 60s 70s and early 1980s and you will notice the page after page of project on making boats planes etc, campare it to those same magazine of today….. you will find nothing like that

~ that is fascinating. being state-side i knew nothing of Rod Jolley, but with luck i’ll find an image of the ‘glass front to assuage my curiosity. did the one-off fiberglass front end resemble Sydney Allard’s original?

In September 2009, I spent an entire afternoon at Rod Jolley’s shop in England.

His craftsmen duplicate the construction methods of the country of origin for all of his restorations (and they do vary greatly). He took the time to talk me through each

of the different methods of body fabrication as I watched the work in progress. I learned a lot that day.

Hi Scott, Yes there are published pictures of the car in one of the small format magazines from the fifties. I believe it is in “Hop Up” but I will have to verify that. There is a story about the restoration of the car in a Brooklands Book simply titled “Allard”. The car was discovered and restored by Dudley Hume. Rod Jolley did the body. The article says the glass body was of RGS-Atalana origin, but we know the body was a one-off built in the US in period. I suppose there is a chance that the car had a second glass body installed at some point, but I would bet that the body that was scrapped was the actual LeMay body.

General LeMay owned a few Allards. He also owned an Allard JR and LeMans. One of his Allards was partrially rebodied with a one-off fiberglass front end which I believe was thrown away during a high dollar Rod Jolley restoration back in England.

~ wow– thank you for filling in the outline, Erich. do you suppose any pictures still exist?

~ General LeMay owned an AllardJ2 and was an active member of Sports Car Club of America. he is said to have ‘loaned’ Strategic Air Cpmmand air base runways to the club for racing events and was inducted into the SCCA Hall of Fame for his contributions and support.

in the mid ’50s my dad, who denied being handy and swore he was no carpenter, constructed a large addition to our home and built 2 complete garages on our lot with only the help of his 5 sons. maybe one day i’ll figure out how he found time.

Great article, Geoff.

I’ve been a DIYer for 75 years—my granddad introduced me to tools at the age of seven. We paneled the basement with the old oak flooring from the house, replaced because it had been sanded too many times. We straightened the old flooring nails and used them again (it was the Depression, remember). All our tools were manual; no power tools until the ’50s.

Merrill Powell

So what kind of chassis is the Major General working on?

The chassis appears to be a Corvette C1 chassis with the Blue Flame Six engine.