Hi Gang…

What a fun article this must have been to write back in the day.

Building your own sports car that could compete as well as handle nicely on the road was something many young men dreamed of. By 1960, this was getting harder and harder to do, but Ray Hixon of Indianapolis, Indiana did it – and the story was covered in great detail in “On The Grid” Magazine in September 1960.

Let’s see what they had to say about building your own sports car with a Devin body.

Built Your Own Competition Sport Car For Only $2920

On The Grid: September 1960

By George Moore

Mechanical ingenuity is a tricky thing. Generally, the fruits of such a particular talent bloom at their best when money is short and the engineering handbook basically consists of the magic touch to do what is right through experience.

The competition sports car gracing these pages is an example of this touch for the machine is not the product of a well-padded pocketbook. It was fabricated in the rear of a Chevrolet agency’s service department. And its construction will give hope to those individuals who dream of someday creating their own personal sports job on a limited budget, because it represents an investment of exactly $2920.

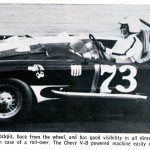

The automobile has been the recent project of an Indianapolis used car manager named Ray Hixon who set out to prove it was possible to develop a relatively inexpensive racing car, providing two principals were rigidly observed. One was to come up with a car which would be basic enough so no difficulty would be entailed in making it run. The second was to keep the cost nominal by sticking to standard parts. This meant modifications must be kept at a minimum.

The art of scrounging up some old as well as new parts in work of this undertaking will stand any constructor in good stead, because the ability to uncover the necessary component pieces at the right price has, of course, an all-important bearing on the ultimate cost.

The art of scrounging up some old as well as new parts in work of this undertaking will stand any constructor in good stead, because the ability to uncover the necessary component pieces at the right price has, of course, an all-important bearing on the ultimate cost.

Fortunately, the Chevrolet Corvette has many components which are adaptable to a project of this nature. And their availability liberally contributed to the finished product.

Hixon wanted a machine smaller than a Corvette, so to use parts off one of the fiberglass jobs meant reworking them in order to have everything proportionate.

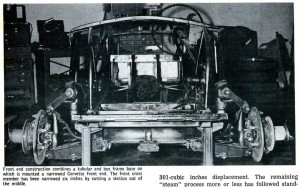

To accommodate a 91-inch wheelbase, a Corvette front cross member was narrowed simply by whittling six inches from its center.

The rear end entailed a bit more doing though, for to shrink the rear tread eight inches it was necessary to cut and re-weld the housing, then re-spline the ends of the axles themselves to mate with the ring gear carrier and differential assembly.

Suspension is straight out conventional coil springs in front and leaf in the rear. And while this arrangement may not especially fascinate the independent rear enthusiasts, it’s a lot cheaper and a lot more reliable than either swing or De Dion axles as all the components are heavy duty competition equipment available from Chevrolet.

The frame radically departs from the currently popular concept of welded tubing. It is not made of tube. It is constructed from box channel, because a pair of stock car mechanics, Jim Garrison and John Lee, who worked on the machine argued that while the tubes were more rigid for the considerable difference in cost the channel would not be at such a disadvantage there would be nothing to recommend it.

The frame is fabricated from two-inch by three-inch box and has a kick-up at the rear only. Lateral stiffness has been added by one-inch tubular cross braces, and stress tests have indicated no marked degree of flexibility.

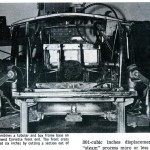

Possibly the easiest place for a builder to go wrong is the engine. Since being a sales manager doesn’t qualify anybody as being a mid-West Midas, the powerplant problem was solved by plucking some V-8 components out of the parts bins and boring out the block to four inches in order to get 301-cubic inches displacement.

The remaining “steam” process more or less has followed standard procedures, as heavy duty valve gear, polished rods, Corvette rods, and Forged true pistons constitute the reciprocating assembly.

The heart of the engine, the camshaft, was ground by a local concern, Gallivan Engineering. And the scavenging department contains a bit of the “built in Indiana” touch, for the fellows made their own headers and pipes.

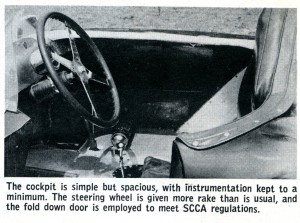

Back of the Corvette four-speed gearbox it was deemed advisable to jump the pressure plate spring pressure upwards to guarantee a minimum of clutch slippage upon hard acceleration. The pressure on the stock Corvette plate was stepped up from 1850 pounds to 2800 pounds, then a servo-assist for the clutch was installed so the added compression would not cause undue fatigue in the driver.

The servo has been split between two hydraulic cylinders. A Chevrolet master unit accommodates the foot pedal, and a bell housing mounted Ford truck slave unit operates the clutch linkage itself.

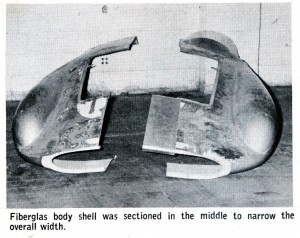

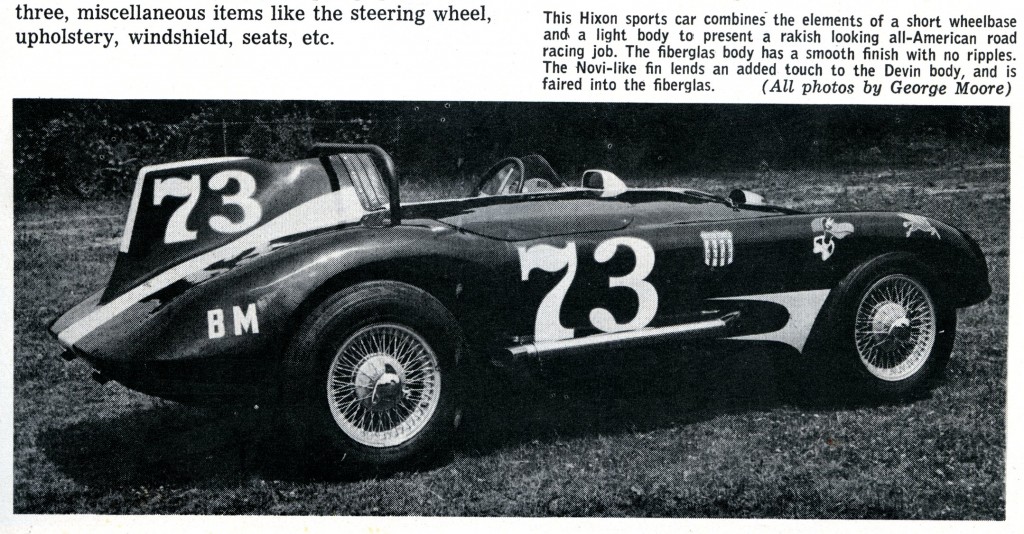

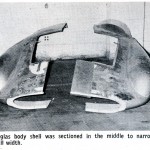

A certain amount of latitude always is permitted when obtaining a skin for an automobile. Hixon went neither long nor short on finances for the body, but merely took a second hand fiberglass shell and adapted it to the chassis.

The shell originally was made for a more narrow tread, thus it was necessary to cut the fiberglass along the centerline and widen it four inches with an aluminum panel insert.

The shell originally was made for a more narrow tread, thus it was necessary to cut the fiberglass along the centerline and widen it four inches with an aluminum panel insert.

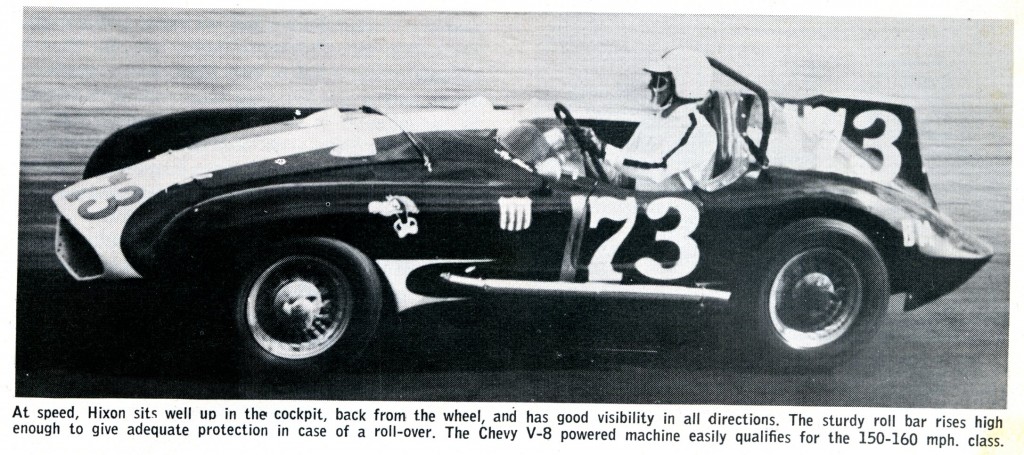

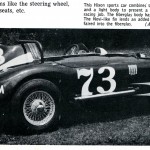

Personalized styling has been added to the body by incorporating a Novi-like fin into the tail section. The fin is not bolted on, but is blended into the material so smoothly it could pass for an original fabrication.

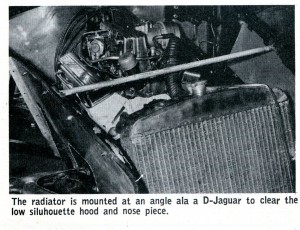

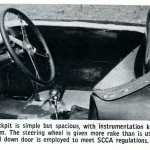

To clean up the completed automobile, a number of secondary items such as a radiator mounted at an angle ala the D Jaguar; Corvette brake drums and ceremetallic linings; a set of Dayton wire wheels and knock-off hubs; Corvette steering linkage; and Stewart-Warner instruments were added to finish the machine.

There is nothing sensational here, to be sure, but all these parts are good basic speed equipment which can be purchased upon an across-the-counter basis. And the very nature of their availability keeps the cost element down.

Obviously, it is impossible to build a car for nothing. But considering the end results achieved from this venture, the final product was acquired for a very nominal sum. The cost element can be divided into three categories: one, the body, frame suspension, axle and running gear; two, the engine, transmission, and hop-up equipment; and three, miscellaneous items like the steering wheel, upholstery, windshield, seats, etc.

The first group almost ran a dead heat with the engine-transmission category, for the frame-body-suspension segment represented a total outlay of $1160 while the engine-gearbox combination came to $1295. Actually, the powerplant itself, including all the power modifications, cost only $950.

But an additional $345 was spent acquiring a brand new fuel injection system. Miscellaneous pieces were lumped together for a total of $400. And an extra $65 was expended later for a second set of adaptors for the Dayton knock-off wheels.

This particular machine, which has the appearance and performance characteristics of the best imports from Europe, clearly illustrates it is possible to build a competition car at a cost less than the purchase price of many popular Detroit models. All a builder needs to do is not be afraid to get his hands dirty, and determine in advance just what direction he wants to go.

The most factual statement ever uttered is, “If you’re going racing, bring money.” However, in this case, don’t bring so much.

Summary:

It would be neat to know how well this car performed once it was ready to compete – and perhaps it is still around today. If any of you know the rest of the story about the “Ray Hixon Devin Special,” let us know here at Forgotten Fiberglass. We’d love to share it with everyone here as well.

Hope you enjoyed the story, and until next time…

Glass on gang…

Geoff

——————————————————————-

Click on the Images Below to View Larger Pictures

——————————————————————-

I did a quick search of the name “Ray Hixon” on Racing Sports Cars and located these results:

http://www.racingsportscars.com/driver/archive/Ray-Hixon-USA.html

The car ran in B Modified which would have made sense in SCCA back at that time. Also, on the link below, Bud Gates is listed as a co-driver to Ray:

http://www.racingsportscars.com/driver/Ray-Hixon-USA.html

This supports Glenn’s comment above.

A very cool car that would make a nice find today.

Glenn….thanks for the extra info. If anyone can find this car…it’s you in Indiana. Go get ’em Glenn! Geoff

I think that this article was penned by George E. Moore who was the automotive writer for The Indianapolis Star. He wrote columns entitled ‘Speaking of Speed’ and ‘Speaking of Cars’ for the newspaper. Although technically minded, he had the ability to write in a layman’s language, as he has done here. George died at the age of 83 in September of 2003. While I don’t remember Ray Hixon, I do remember Bud Gates who raced a Corvette with a similar rear tail fin – Ray Hixon may have been the used car manager for Bud Gates Chevytown? Don’t know for sure.