Car designers are artists – sculptors as you would say – creative down to the last bone in their bodies. Their talents inspire us in thought, action, and deed, and when it comes to the automobile…. many of the designs these artists came up with in the ‘50s were breathtaking.

But where did you go to learn to be an automotive designer? How was this talent nurtured and developed?

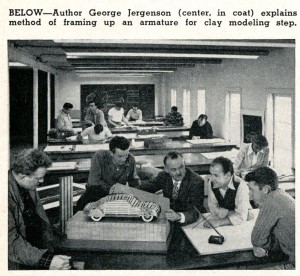

This process of teaching design was just taking shape in the postwar years and Motor Trend captured an excellent early story in ’49 penned by George Jergenson who was the head of the Transportation Department at the Art Center School of Design in Los Angeles, California.

Let’s see what Jorgenson had to say about the art of automobile design back in ’49.

Styling Is An Art: Motor Trend, October 1949

By George Jergenson

Note: Mr. Jergenson, who now heads Art Center School’s transportation department, was, for 11 years, the chief designer for General Motors Cadillac Division. He is using the knowledge gained there to considerable advantage through instructing some of our future designers. A resident of Santa Barbara, he is considered an authority on automotive and other transportation design – Editor.

The keynote to automobile design is realism. Without this, designs may be made that are neither practical nor advisable. That is why Art Center students are taught the General Motor’s method – that of designing, then actually building the individual design.

About one quarter of Art Center School’s total student body of 1000 young people specialize in the study of industrial design during their third and fourth years.

They have by this time received training which is basic for the practice of any of the visual arts in drawing, painting, modeling, anatomy, perspective, in free designing in two and three dimension, in color science and in solving spatial problems

They have already learned to work within the limitations of materials and techniques and, at the same time, to improvise new designs and uses for them.

But when they enter the courses which are planned to fit them for the practice of industrial design, the profession in which they hope to serve as useful members of society, their training becomes eminently practical.

The instructors, who divide their time between teaching and successfully practicing industrial design, believe, along with the school’s founder-director, Edward A. Adams, that graduates of an art school who cannot make a living with what they have learned have not been given the right instruction.

They believe that before young designers can hope to influence the design of goods industry produces, they must know how they are designed and with what limitations and objectives industry produces them. The young industrial design student at Art Center School learns to work realistically as he will have to do when designing for industry. These are as much elements of industrial design as are the purely artistic ones.

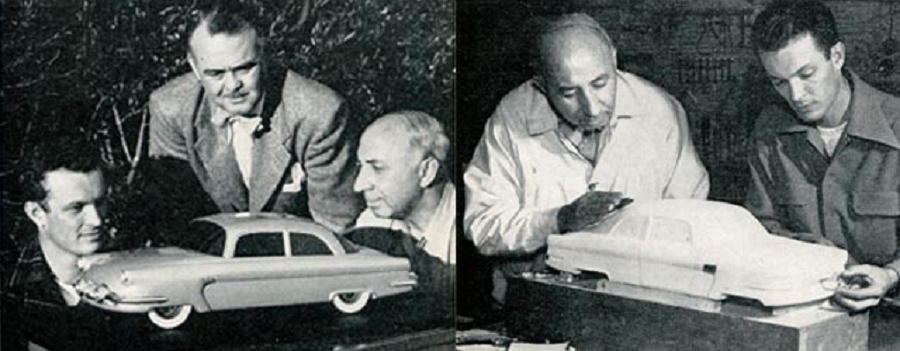

In automobile designing, the students follow all the steps in design problems from blueprints, sketches, templates to the final scale clay model. They do not, however, do metal or woodworking themselves. As in industry, this work is done by an expert craftsman. The student’s mind is kept free for further designing.

Art Center School teaches the same methods in car styling instruction that are followed by General Motors and other automotive manufacturers. Thus Art Center School graduates are able to step directly into the styling sections of the industry with a full knowledge of procedure.

This saves the student time and saves the industry both time and money. Important executives of General Motors make frequent visits to the Industrial Design Department, offering criticism, advice and acquainting the students and faculty with the latest trends in the field.

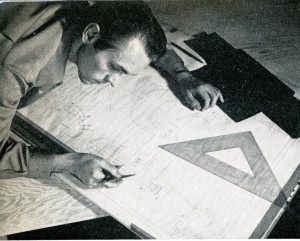

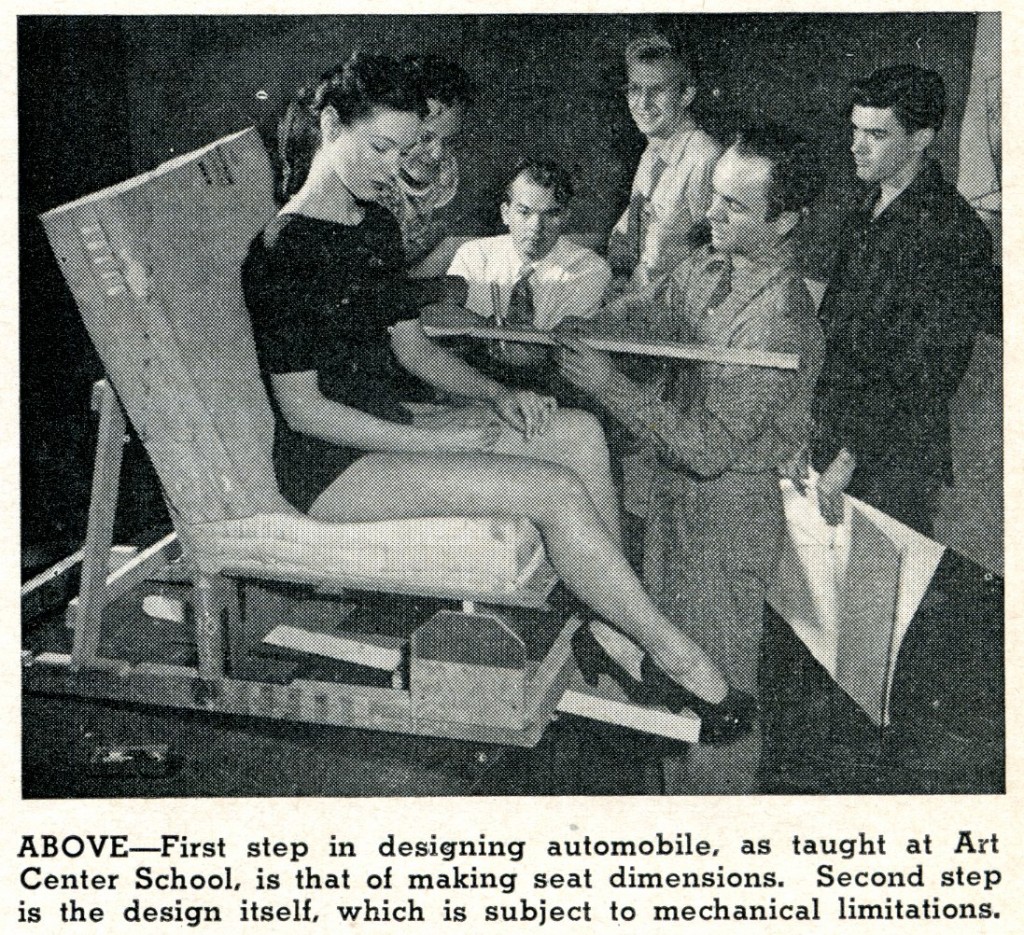

The first step in the design of an automobile, as taught at the school, is a thorough study by the student of blueprints of existing models.

The first step in the design of an automobile, as taught at the school, is a thorough study by the student of blueprints of existing models.

This includes research on the mechanical limitations against which they are designing: wheelbase, tread, seat dimensions and locations, head room limitations, location of engine and drive units, cost, availability of materials and tooling problems of the manufacturer.

The student then reduces an actual manufacturer’s drawing of an existing model to 1/8, ¼, or 3/8 scale, whichever is decided upon. He then makes a set of dimensions from the reduced drawing.

The next step is the sketching of the design that he wishes to carry out.

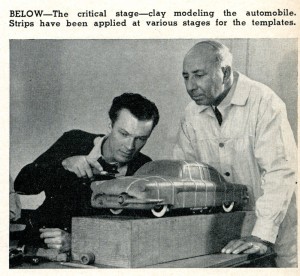

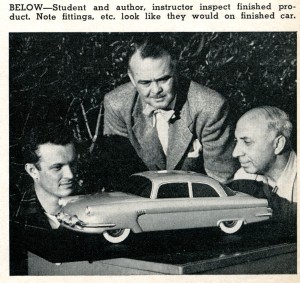

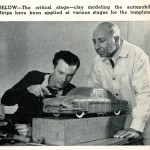

When he has decided upon the final design sketch, the student then makes a three-view color rendering to proper scale. Criticism by the instructor is given on each step. This helps iron out many problems. Using the three-view drawing on vellum, the surfaces are next developed and sections are made for wood templates. The clay model is then built to prove the student’s design in three dimensions which is final proof his design is okay.

Changes, if any, are made at this point. If changes are necessary, new templates are made from the clay model and the drawing is revised to fit these changes. Final step is a plaster, wood, or a combination mockup. Proper finishes for all parts are used so that the mockup looks exactly like the finished car would when manufactured.

A great deal of research and study is done by the students in the car styling classes. Field trips are made to study latest developments in new automobile models, manufacturing methods, tooling, and customizing. This type of practical training in automotive styling is that which is necessary to prepare students for the designing field. And without the constant influx of fresh, young ideas to prove that styling is an art, automotive designs would become stereotyped.

Many of the founders of the companies that produced the fiberglass bodies of the ‘50s were associated with Art Center in one or more ways. Some gave lectures like Bill Tritt of Glasspar.

Some were students like Merrill Powell and Hugh Jorgensen of Victress – and Jorgensen went on to be an instructor at Art Center. Some companies hired students to work on their projects such as Howard “Dutch” Darrin and the folks at Victress.

Some students like Chuck Pelly of famed BMW design worked for companies such as Victress where he designed some of the quarter midgets they built in ‘glass.

The Art Center of Los Angeles had a formidable influence on the design, construction, and creation of many of the fiberglass sports cars that debuted in the early and mid ‘50s in Southern California. And…we’ll continue to feature articles here at Forgotten Fiberglass on this significant and exciting school – and other schools of design – that helped mold and shape young designer minds across the country.

Hope you enjoyed the story, and until next time…

Glass on gang…

Geoff

——————————————————————-

Click on the Images Below to View Larger Pictures

——————————————————————-

Hello Mr. Hacker!

I was delighted to come across your article! I’m thinking that, given all the photos posted in the article, you might actually have or have access to a copy of the 1949 October issue of Motor Trend.

This might be a long shot but I’m doing research about a relative, my great aunt’s first husband, who was featured in the Motor Trend Magazine in October of 1949 for a car he designed. His name was Dean Mix and there is supposedly a picture of him standing in front of his car in this issue. After selling the car to someone, he went missing, last seen in September of 1949 in Grand Central Station. I am very interested in seeing the pages that might relate to him and if there is any way I could receive a scanned/emailed copy of those pages, I would be very much obliged. Thank you so much! Crissey Hewitt

Another side bar to being at Third Street was to walk through the staff parking lot. A few cars stood out. Tink Adams, Prez drove a 1955 Lincoln hardtop for years. The two main gals in the office had a deep red Porsche 356 convert. [it had a nardi steering wheel which I copied for my TD. made it in the model shop – still have it] The other gal had a black 1960 Corvette. It was generally said to buy a black one as the bodies were finished much better. George J drove a blue 54 Lowey Studebaker and in 1961 his brother gave him a mint 1958 light green with white insert Corvette. Mac had his 120 Jag and a 1959 Corvair 4 dr he painted black with a silver top – kind of an attempt to give it some class. Ted Younkin – product design instructor had one of the first 61 Corvair coupes RED. None stood out like Jim Webb’s car.

Hugh, Mel….great information and I very much appreciate you penning your thoughts and memories down of this special place and time. I have so much admiaration for those of you who went to Art Center – what a special time that must have been in your lives. Very neat! Thanks for sharing….Geoff

When this article was done Joe Thompson had only been there a short time. He had worked for Raymond Lowey at Studebaker on their 1947 cars. George Jergenson was an early member of Harley Earl’s design department at GM. He worked on the 1938+ Cadillac 60 special under Bill Mitchell. The war years put many designers out of jobs when car production stopped in 1942. Joe was likely 62 or 63 at this point. He was still going strong 11 years later when I got there, and lived into his 90s. He was said to be America’s second auomotive clay modeler. For many years he was manager of Cadillac’s Sample Body Department [their porto-type shop]. This was long before computers converted drawings into body dies. He developed patterns much as guys did their bucks for early fiber glass bodies – lots of assembled templates.

Another student that went to Art Center was a guy named Mel Keys..Those years from 1954–1957 were the most fun i ever had.Because we were all interested in the same “CAR”I found out about

Art Center from a magazine article ,I think it was in Motor Trend in 1952..Hugh Jorgensen and Chuck Pelly were going there the same time I was.I don’t think Merrill was tho..Pete Brock of Shelby fame was going there too..

Funny thing I don’t remember seeing any cuties being measured for seat fitting,,

Mel