Hi Gang…

There’s no way Forgotten Fiberglass is the work of just one or two car guys. This is a team, gang, and I do my best to introduce you to all of the players across the world. Today I have the pleasure of introducing you to good friend and historian, Bob Cunningham.

I was introduced to Bob and his wife Cathy via Daniel Strohl of Hemmings in our mutual pursuit of the history of prewar American teardrop streamlined cars (yes….I do have other hobbies that are not just fiberglass cars….. but I don’t stray far from the path).

Here’s The Mars Express – A Car That Bob Cunningham Has Extensively Researched And One That We All Hope Is Lurking In Some Barn or Castle Out There…

Bob is a consummate historian for obscure, orphan, and what I think are fantastic cars. He goes beyond most I’ve seen to document the history and significance of these cars, and has produced two volumes in a series on “Orphan Cars” that will continue with at least one more volume (I’m saving space on my shelf for your next book Bob!). Checkout his website for additional information:

http://www.orphanbabycars.com/index.html

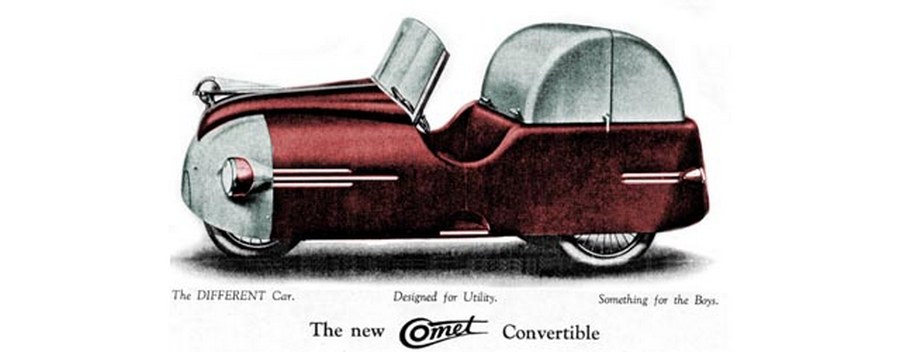

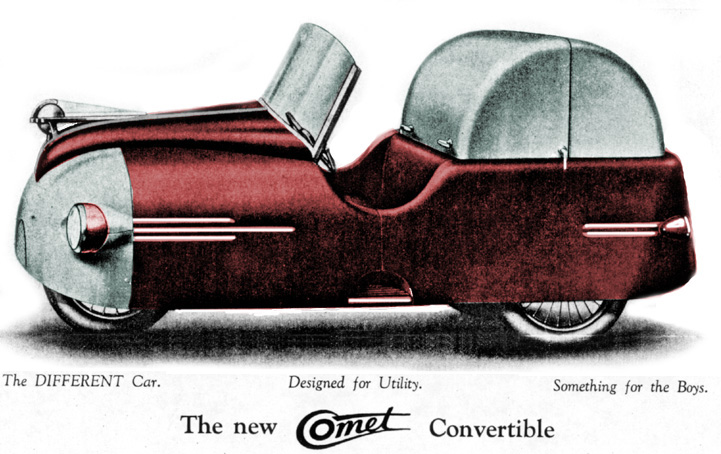

I’ve been working with Bob to both understand and document the use of fiberglass and plastics in cars in postwar America. One of the cars that was a bit unusual to me was called the “Comet” and appeared in print in 1947. Although small in stature, it was going to have a fiberglass body, so I got on the phone and asked Bob if he knew anything about it. Sure enough, he did – but not just anything….he knew most everything about it.

I was impressed.

After some begging and pleading on my part, Bob graciously agreed to write a piece for Forgotten Fiberglass that would cover not only the Comet but two other related cars – all designed by the same person.

With no delay, let me turn over the reins to Bob Cunningham and let him tell the story of Julius Rose and his three little cars. Take it away Bob!

Julius Rose And The Three Little Cars: Comet, Marvel And Featherlite

By Robert D. Cunningham

Author: “ORPHAN BABIES: America’s Forgotten Economy Cars” (http://www.orphanbabycars.com/)

Considering the circumstances, it’s easy to see why folks bought into the dreams of one Julius Rose.

Midway into 1945, a fragile peace had finally settled over a mortar-pocked globe. Weary American soldiers ached for the tedious boredoms of yesterday…but with certain advancements. Expectations had been raised by a growing army of industrial futurists. Technology, they said, was poised to transform the mundane into the marvelous; the toilsome into the convenient; the simple into the sophisticated.

Everything would be new. And wonderful. And plastic.

Although premature, such promises had served a noble purpose: They inspired the tired. But when war ended and arms were put down, the American industrial complex was ill prepared to make dreams come true. Our once Depression-lean corporations had grown fat on the fruit of remarkably short lifecycles; Jeeps and trucks had been deployed and destroyed in a matter of weeks, and each lucrative order had been followed by another. Retooling to put simple facelifts on prewar products would take many months. And the evolution for which the market clamored? Why, that was years away.

And so, otherwise rational investors were ready to take a chance. They bet on Julius Rose. His was the Story of the Three Little Cars: Comet, Marvel and Featherlite.

Comet

Rose emerged in 1946 with the promise of an entirely new type of light car, both in design and construction. His Comet convertible–“the world’s handiest run-around-in car”–would surely revolutionize the industry. Conceptual drawings depicted a runabout that measured 114 inches long and 48 inches wide, matching the prewar Crosley.

But construction methods for the three-passenger, three-wheeled car would be completely different. Its tubular chassis and body-support framework would be arc-welded into a single unit to roll on 26-inch spoked motorcycle wheels. A single-cylinder, 4-1/2 horsepower, air-cooled engine would be carried at the rear between the car’s only suspension–two 18-inch coil springs.

Weighing in at only 175 pounds, the front of the grocery-getter was so light that it could be lifted and hooked to the bumper of another car–ideal as a service pickup car for garages. Rose claimed astounding fuel economy of up to 100 miles per gallon.

Here’s An Illustration of What The Comet Was Going To Look Like. It Was Going To Be Built Out Of The New Wonder Material – Fiberglass!

Like all postwar wonders, the Comet’s maroon-tinted body would be made of fiberglass. Its design was unlike anything on the road; in fact, it rather resembled a rubber bath toy. Behind the bench seat, a large parcel area with rounded corners was covered by a plastic dome. The dome would raise and lower in bread box fashion.

A “flexiglass” windshield and removable top would protect the occupants. Initially priced at just $320, the Comet seemed too good to be true. Better yet, anyone who put 15% down on a franchise could preorder at a 25% discount. Remarkable, indeed.

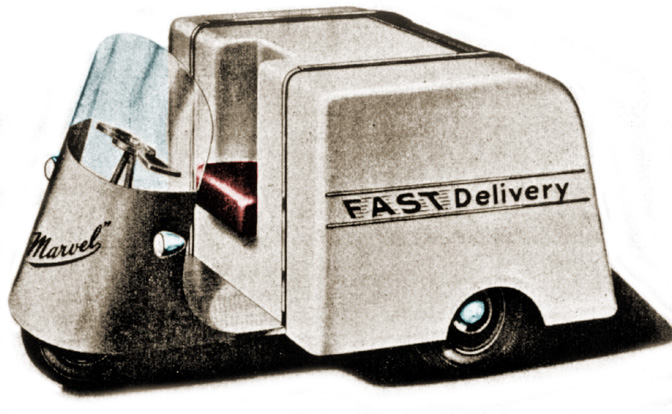

The second of Rose’s wonder cars was a light duty truck.

Marvel

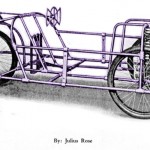

Promotional text for the Marvel Delivery Car described “a dream come true for many a storekeeper who is looking for a 1/2-ton car that is both practical and economical.” The single-passenger vehicle was built on the Comet’s three-wheeled chassis, but featured a cargo body with a built-in driver’s seat.

Available only in white, the little truck resembled an ice cream vending cart mounted to a motor scooter. The $600 Marvel was less than 6 feet long, 3-1/2 feet tall and 4-1/2 feet wide. It was equipped with a rear-facing door that slid on runners over the top of the cargo box.

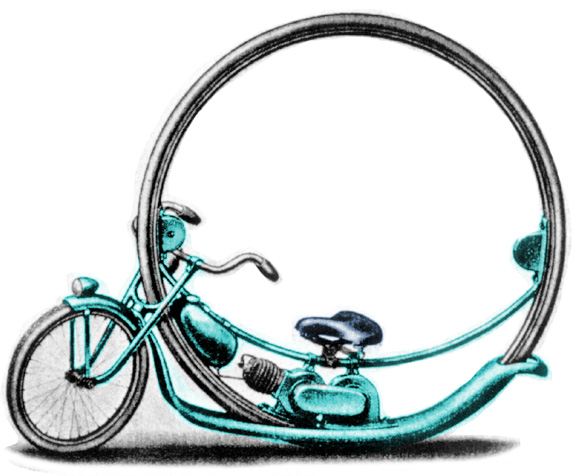

Surely every modern mother would love a Comet. Dads would drive Marvels. And the kids would get behind the wheel…actually, inside the wheel…of Rose’s third little wonder.

Featherlite Motor-Wheel

The Featherlite Motor-Wheel was primarily designed for youngsters, but Rose predicted girls and boys of all ages would be attracted to the unique conveyance. The Featherlite front wheel and fork would be similar to any other motorbike with a standard tire. But the fuel tank, engine, seat and driver would be housed entirely within the 60-inch rear “tube-in-one-tire.” Rose said $160 could bring one home, so why not buy two?

Having proposed three of the strangest little vehicles imaginable, Rose set about actively soliciting investors and dealers. He said his General Developing Company, of Ridgewood, Long Island, would be “consumed with Comet production” in short order.

He readily granted distributorships on the condition that franchisees would assemble the vehicles themselves. In addition, distributors were required to sign a contract to take delivery of no fewer than 100 cars per year, for which advance partial payment was required. As for when to expect delivery, well, Rose would let them know in due time.

That time never came. Impatient investors lodged protests with the Postmaster General.

On April 15, 1948, Julius Rose was denied the use of the U.S. mail system. He was banned from sending or receiving mail under either his own name or that of General Developing Company. The Post Office informed Rose that soliciting and obtaining funds for dealers’ franchises was illegal when he “had built no such cars and was not in a position to make delivery at any reasonably early date.”

The Postmaster General claimed Rose had used false and misleading representations in obtaining money both for franchises to sell the non-existent car and as down payments on the vehicles themselves.

The following year, Rose was tried on a criminal charge…and acquitted. Enraged by the loss, the government viciously pursued others. One by one, legitimate start-ups broke down under allegations of fraud: Tucker, Playboy, Davis. Buoyed by his victory, Rose published his version of the events in a book entitled, “The story of the Comet: (or, The case against the unrealistic bureaucracy).”

Nevertheless, the Brooklyn postmaster refused to deliver personal mail at Rose’s Brooklyn address for more than ten years. In 1958, Rose filed a protest against the “unheard-of arrogance of the bureaucrats in the Department.” The postmaster countered that Rose had continued to promote the Comet and Marvel; on updated fliers, prices had been increased more than 30%. Rose denied the allegations, contending the legal documents provided by the Post Office were “full of dirty lies and misstatements.”

Yet, thirteen years later, Julius Rose was before the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, in Washington, D.C., promoting the very same cars. “I have developed two new-type lightweight pollution-free cars,” he boasted. “The Comet and the Marvel Delivery Car.” He didn’t get into the details of how they were to be pollution-free because he had more urgent matters to discuss.

“I have also concerned myself in recent years with the problem of effective civil defense in case of an atomic war by working out a very detailed plan for Survival Towns. Besides being now in the process of building Helgoland, a small community where some of my new-type lightweight cars are to be built, my company has also offered to cede part of its properties to the government and to construct a complex of houses embodying the new construction method that could then be used as a training center for construction teams.”

Rose’s self-centered vision included not only thousands of his little cars, but an eminent atomic attack upon America’s cities. In preparation, he had founded the Christian Survival Fellowship. Its members would populate his Survival Towns. “Community spirit tends to dissipate as soon as the population goes much above the 10,000 mark,” he said, so he urged the federal government to invest in his plan for 5,000 new communities of 5,000 people each. “The new communities should be located sufficiently far enough from any city that they cannot be considered part of its suburb,” Rose said. The distance would be sufficient to isolate his villagers as the larger cities disintegrated into nuclear fallout.

As Rose exited the hallowed halls, he left the bureaucrats to ponder his proposal. Meanwhile, we drafted our young men and shipped them off to Viet Nam. Our colleges became hot beds of protest and anti-government sentiment. Traditional values were cast aside for sex, drugs and rock’n’roll.

Considering the circumstances, it’s easy to see why folks bought into the dreams of one Julius Rose.

Copyright 2011 Robert D. Cunningham

Summary:

What a great story and thanks much to Bob Cunningham for sharing this with us. Again, information on the use of fiberglass (or intended use) in immediate postwar America is slim, and Bob’s willingness and interest to help flesh out these details and stories is very much appreciated. And… very interesting “backstory” on Julius Rose – particularly later in his life. Thanks Bob for a great article!

Hope you enjoyed the story, and until next time…

Glass on gang…

Geoff

——————————————————————-

Click on the Images Below to View Larger Pictures

——————————————————————-

- Here’s The Mars Express – A Car That Bob Cunningham Has Extensively Researched And One That We All Hope Is Lurking In Some Barn or Castle Out There…

- Here’s An Illustration of What The Comet Was Going To Look Like. It Was Going To Be Built Out Of The New Wonder Material – Fiberglass!

- The Marvel Delivery Car – Surely This Was To Be Built In Fiberglass, Too.

- Here’s The Featherlite Motor-Wheel. Ok Gang…Surely “No” Fiberglass Here.

Hello Bob I was wondering if you have ever heard of the car ,the (Geni) it was supposed to be a steam-powered small car of 1970,and from portland oregon.I found it listed in a All Car Marques registry.If you do know of it could post a picture of it,I certainly would appreciate it.Thank You. Sincerely Kevin Gibbs